The rifle is arguably the most important piece of equipment to the hunter—with a possible exception allowed for the equipment which sits between the hunter’s ears.

Finding a rifle that suits your body and shooting style is paramount to placing your shots accurately and having a good day at the range or in the hunting field. Rifle action, length of pull, type of sights, and trigger pull must all suit your preferences. This intensely personal nature of the rifle is probably one reason that debates rage year round all over the internet about the best hunting rifle. It is impossible for me to prescribe which rifle is best for someone else; all I can do is describe my rifle and my preferences and hope that the information is valuable to others.

The rifle that I use to hunt small game is a Browning BL-22 Grade I—a lever action rifle chambered for the .22 Long Rifle, .22 Long, and .22 Short. I have owned this rifle for about three years now and have used it to bag my first (and only) squirrel.

Prior to owning the BL-22 I owned the now discontinued Marlin 925, also chambered for the .22 Long Rifle. The Marlin was my first gun and I never did take it hunting. The Marlin was a decent gun—it was affordable, comfortable to shoulder and shoot, and was plenty accurate. I sold it for the sole reason that I am a left handed shooter and the Marlin was a right handed bolt-action rifle. I was initially unfazed by this, but as time went on I got annoyed with reaching over the receiver with my left hand to work the bolt and I never got the hang of using my right hand (the one that supports the fore end of the rifle) to reach back and work the bolt.

When I began the search for the rifle that would succeed the Marlin 925 I debated between getting a left handed bolt action rifle and a lever action rifle. At the time—and I believe it is still the case—that the only left handed .22 bolt actions are the CZ 452 (either Lux or American) and the Savage MK II series in a variety of configurations. I have never been one for synthetic stocks, thumb-hole stocks, and the like, so the only Savage MK II for me would be the GL model, which comes with a simple wood stock and iron sights.

I have never had much interest in auto-loading rifles so I never even considered one as a replacement for the 925. Besides, many states don’t allow hunting with a semi-automatic rifle and I had plans to take up hunting.

I eventually ruled out the bolt actions because I have always been a sucker for the Old West and Western movies, so the lever action guns are a natural fit. Additionally, if I ever took my right handed friends shooting they would be able to comfortably shoot a lever action, but not a left handed bolt action rifle.

It is worth mentioning at this point that I was looking for a new rifle, not a used one. Used guns have a lot to offer over new guns and I will admit it was a questionable tactic to look only at new guns, but I am unabashed in my preference for things which are new and shiny, so I limited my search accordingly.

The next step was to determine which lever action .22 was best for me. The choices at the time were the Henry rifle in a couple of configurations, the Marlin 39A, and the Browning BL-22.

First to be eliminated was the Marlin 39A. New Marlin 39As were, and continue to be, rarer than a hen’s tooth and quite pricey. Furthermore, at the time Marlin was receiving streams of negative reviews about their quality control after their recent acquisition by Remington. I would still like to have a Marlin 39A, and hopefully they will appear on shelves again someday soon. (For the record, my recent internet surfing indicates that Marlin quality control is back at acceptable levels)

The Henry offers good value in a lever action rifle and my reason for passing on the Henrys is not really a good one. Henrys look good and I hear they shoot very well too, but the sticking point for me was the use of a painted/coated “alloy” receiver cover instead of a blued carbon steel one (I put alloy in quotes because I am aware that steel is itself an alloy, but the Henry alloy is composed of non-steel components). I am sure that the receiver covers on Henry rifles are perfectly adequate, but I prefer blued steel when I can get it, and I think knowing the receiver cover was coated or painted or whatever instead of blued would have eventually drove me mad. And when I handled the Henry back-to-back with the Browning BL-22, I felt there was no doubt that the BL-22 was the better made product.

At this point it sounds like I chose the Browning by a simple process of elimination, but the BL-22 has several things going for it. First of all, the BL-22 is of outstanding quality. I have not held other rifles made in the Miroku plant, but I have heard they are of equally exquisite craftsmanship. When you hold the BL-22 you know that this is a rifle which will stand the test of time. The wood is beautiful and the blued steel is gorgeous—you could not ask for more.

The Browning BL-22 is also pretty reasonably priced. It is not as affordable as the Henrys, but like I said, I firmly believe you get what you pay for with the Browning. If it could be found in stores, I think the Marlin would have out priced the Browning by at least $100, and I am not sure if it would match the quality. So in my book, the Browning wins the bang-for-your-buck competition.

Finally, the Browning BL-22 simply fits me. I shouldered both the Henry and the Browning and found the BL-22 to be the better match for me.

Are there things that I don’t like about the BL-22? Absolutely.

The wood, while beautiful, is finished with a high gloss lacquer which makes for an impressive appearance out of the box, but soon the gloss finish shows fingerprints, dents, and scratches more easily that a satin finish. I expect my rifle’s gloss finish will take a beating in the hunting woods, but that is what guns were designed for, so I won’t cry over it.

The lever action on the Browning BL-22 has some kind of gearing so that the lever throw is only 33 degrees. This is pitched as an advantage, and no doubt some people love it, but I am a traditionalist and would have preferred a full length lever throw. Moreover, the trigger assembly moves with the lever, as opposed to staying with the stock as on traditional lever actions. Again, I would prefer the traditional arrangement. Both the Henry and the Marlin use traditional levers.

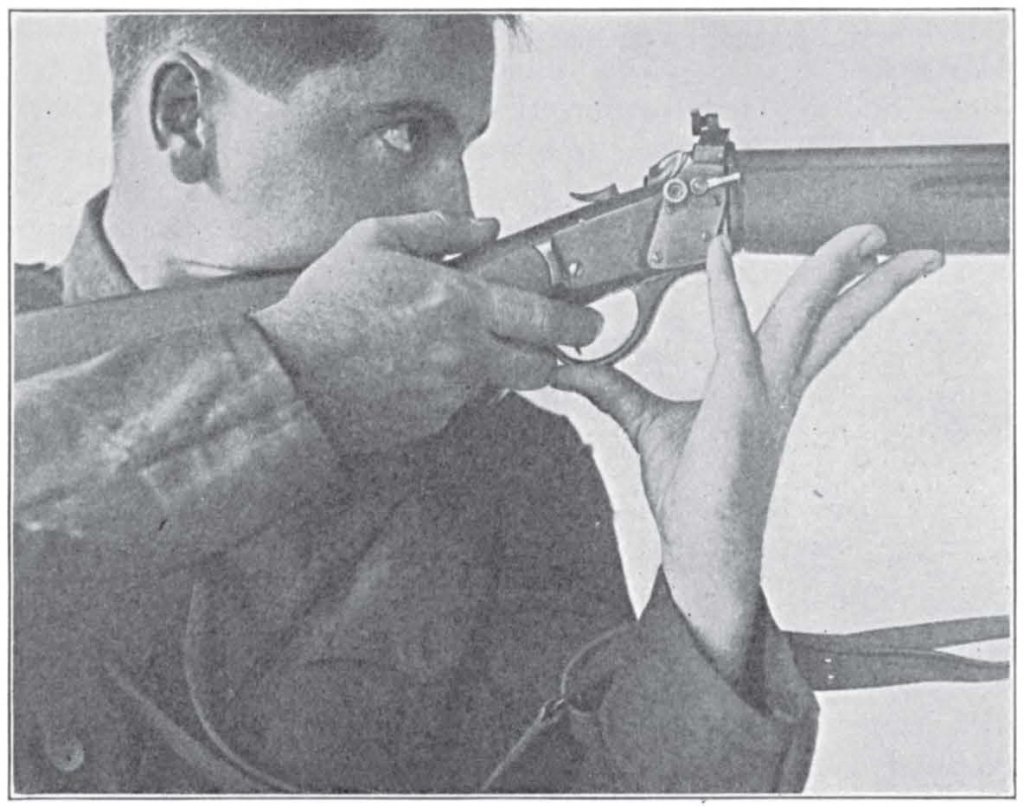

This brings us to the most universal complaint about the BL-22: the trigger pull. I don’t have the equipment to measure the pull weight but I can say for certain that the trigger pull is very heavy. And due to the unique trigger/lever arrangement it seems to be difficult, if not impossible, to lessen the pull weight. When just plinking and shooting for fun the heavy trigger isn’t much of a problem, but when trying to sight in the rifle and make good groups you tend to focus on the trigger pull and it seems monstrous. You can find a collection of Browning BL-22 trigger pull data over at Rimfire Central.

Finally, the stock iron sights aren’t great, but they never are. The Marlin and the Henry have a similar arrangement so this isn’t really something to nit-pick, and it is easy enough to fix. Shooting in low light with the stock iron sights is hard, but I still manage it okay.

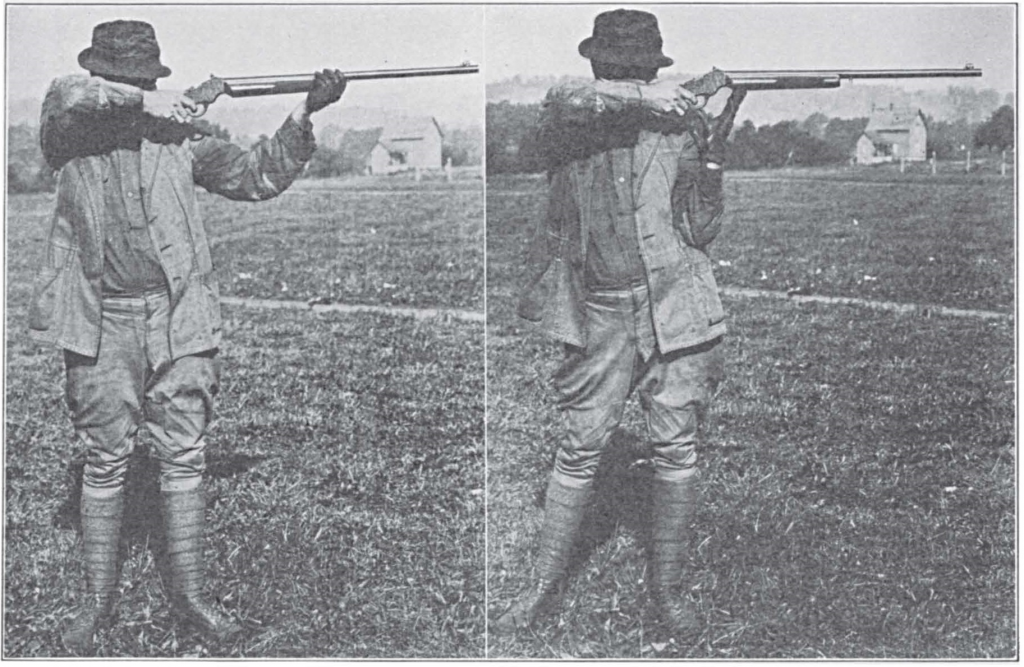

I guess at this point I should say something about the accuracy of the rifle. I am not a bench rest shooter; I don’t like making meticulous groups and therefor I don’t do it. Furthermore, I am not a great shot. I am merely a passable shooter, so every gun is going to be more than accurate enough for me at this point. I enjoy shooting from a standing position at fun targets—empty shotgun shells, steel plates, cans, what-have-you. Because of all the above factors, my ability to give a fair assessment of the Browning BL-22’s accuracy from my own experience is limited.

Someday I will get sandbags—or maybe even a more advanced bench rest set-up—and test the real capacity of the BL-22. Until that time comes, I can say this: When I have done my part and held the sights correctly on the target, the rifle has not missed. If you search the internet you will find that public sentiment holds that of the three major players in the .22 lever action game (the Marlin 39A, Henry, and Browning), the Browning BL-22 is the worst performer. This may be true—I can’t say for sure—but the BL-22 is plenty accurate for my needs and I wouldn’t trade it for either of the other two rifles.

In the next Aspiring Hunter I will go into some more detail about the sights, possible solutions, and sighting in the rifle before hunting season.