The following information on poultry on the homestead or small farm comes from Five Acres and Independence by M. G. Kains. Five Acres and Independence is also available to purchase in print.

Untold numbers of city men dream of a little poultry farm in the country where they can make $2,000-$3,000 a year and get away from all the tensions of city living. And, in spite of the fact that many try it and fail, a good many do succeed.

Those who succeed probably do so because they follow certain sound principles. These include picking out just what type of poultry products they want to produce; the volume needed to make a fair living; and a definite plan for marketing them.

In thinking about a poultry farm, most people probably think first of egg production, for by far the larger proportion of poultry income in the nation is secured from the sale of eggs. Production of poultry meat should be considered carefully also, however, for it not only can supplement the income from eggs, but probably can be produced and sold in a greater variety of ways.

As for volume of production, if you expect to make your living primarily with chickens, it will take a fair sized flock to do it. When the main income is to be from eggs, we do not believe that it is possible to secure a living from less than 600 to 800 hens. Ordinarily, it is estimated that a one-man poultry farm should have at least 1,500 to 2,000 hens if the eggs are to be sold wholesale, and 1,000 to 1,200 hens if the eggs are to be sold at retail.

If you plan to specialize in broiler production, then you probably should grow at least 5,000 a year, and probably twice that many would be preferable.

The method of marketing either eggs or broilers is one of the most important considerations from the standpoint of increasing profit, and yet it is overlooked almost altogether by many people starting in the poultry business. Of course, it is always possible to sell eggs and chickens on the wholesale market at the wholesale price, which may return a fair profit most of the time, but if you want your poultry to return the greatest possible profit all of the time—especially if you are on a small acreage near a city—then it will pay to try to develop a special market for your produce. This may be through a roadside stand if you are located on a well-traveled highway; regular delivery to the homes of customers once or twice a week; or sale to a grocery, restaurant, hotel, night club, or similar type of outlet which will pay you a premium for having a dependable supply of high-quality eggs and poultry.

A little figuring will show very quickly why marketing can be so important. If you will check at your local grocery, you will find that eggs usually are being retailed for at least 10 to 20 cents a dozen more than the usual wholesale price (this margin may be less in smaller towns). If the difference averages only 10 cents a dozen throughout the year and your hens average 15 dozen eggs each, which is not at all unreasonable to expect, this means $1.50 more income per hen. About all of the extra cost is the time required to deliver them and the cost of the transportation. Many times, too, it is possible to get even a premium over the retail price for really fine eggs and chickens. Customers are willing to pay such a premium to be sure of knowing that the eggs and chickens they get are fresh and are of good quality.

Similar premiums can be secured for broilers and for hens which have stopped laying and which can be dressed out for food. In fact, most poultrymen who do direct selling of this kind plan to have both eggs and chickens for sale.

The average person operating a small poultry farm will be better off buying his baby chicks rather than attempting to hatch them. Hatching chicks requires a rather large investment in equipment, which is used for a very short time, and it requires a high degree of skill. Furthermore, it requires a knowledge of poultry breeding to mate the parent flocks in such a way that good chicks are produced.

Selection of a breed also is important to success. If one wants to specialize in the production of white eggs, there is only one really popular breed to select—White Leghorns. If you want to produce brown eggs and meat, or even meat alone, then select one of the heavier breeds such as New Hampshires, White Plymouth Rocks, Barred Plymouth Rocks, or Rhode Island Reds. Crossbred chicks, that is, chicks produced by crossing two breeds such as New Hampshires and Barred Rocks, also are very popular for broiler production and also make good egg producers as a rule.

If white egg production is the only aim and you are not interested or do not have the facilities to grow out the cockerels for meat, then it is possible to buy pullet chicks only, for chicks of all breeds can be separated by sex at hatching time by people who are expertly trained to do that.

In selecting a breed, it is well to talk with other poultrymen in the community and with hatcherymen to find out what breeds are popular in your section of the country. As a rule, you will do better with a breed that is giving good results for other poultrymen in the area. After you have gained experience, of course, you can experiment with other breeds and with lots of different methods of management, but it’s wise to stick with the tried and true methods at the beginning.

If you are producing eggs, most of your chicks should be started in the spring. However, if you are selling to special customers, you should plan to have a steady output of eggs throughout the year. Chicks which are started in April or May will begin laying the following fall and lay for approximately a full year, then go out of production for a few weeks while they lose their feathers and grow new ones. If all of your chicks are started at the same time, this will mean that you will have very few eggs during that period. If you start a brood in February and April, and then a brood the following September or October, you will have hens laying at a fair rate the year round. The customary plan is to start about one-fourth of the chicks in February; about one-half in April; and the other fourth in the fall.

If you have visited many poultrymen, you have seen a wide variety of equipment and methods used in brooding chicks, but the essentials to keep in mind are ways of providing warmth for comfort, feed and water for good growth, and sanitary surroundings to prevent disease. There are many good poultry books, as well as bulletins from state colleges and feed manufacturers, which tell in detail just how to brood chicks.

Most poultrymen keep their laying flocks confined in houses the year round; hence no large amount of land is needed for them. To grow healthy pullets for egg production, however, you should have an acre of range for each 500 pullets or so, and about three ranges so they can be alternated in a three-year rotation. If you have good ground—where a heavy stand of alfalfa, Ladino clover, or other good green crop can be grown—it is possible to grow a much larger number of birds per acre than mentioned above.

Some poultrymen who have only a small farm of their own rent additional ground on which they can grow pullets. This frequently is easy to do because pullets enrich the range on which they run. Still others grow their pullets to maturity in batteries. While this is not as common, yet a number of poultrymen do it very successfully.

Only a small amount of ground is needed for growing broilers. They can be kept in complete confinement either on the floor or in batteries, or if they are allowed to run outside they need only a limited amount of ground. If they have outside yards, however, the yards should be arranged so that broods of chicks can be alternated from one yard to the other.

In growing broilers, commercial producers like to start all the birds their equipment will house at one time and sell that brood before starting any more. If you have a special market, however, it may be necessary to have a regular supply of broilers coming along, and, in that case, you will want to start chicks every week or every two or three weeks.

When this latter plan is followed, it is essential to keep the different ages of birds completely separated. The reason is that if disease should start among the older birds, it may be impossible to keep it from spreading among the younger ones.

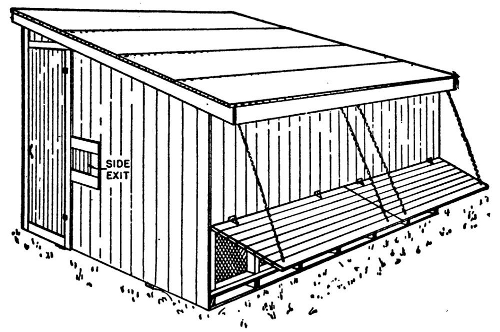

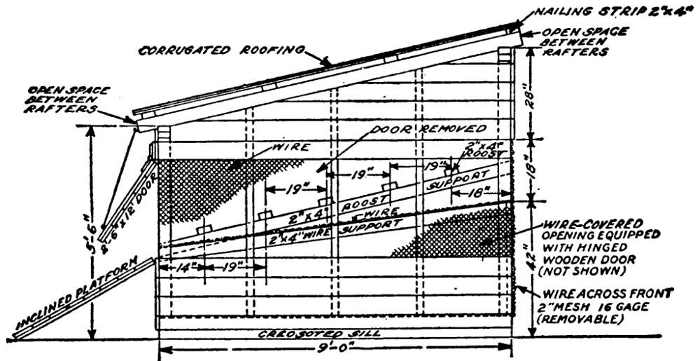

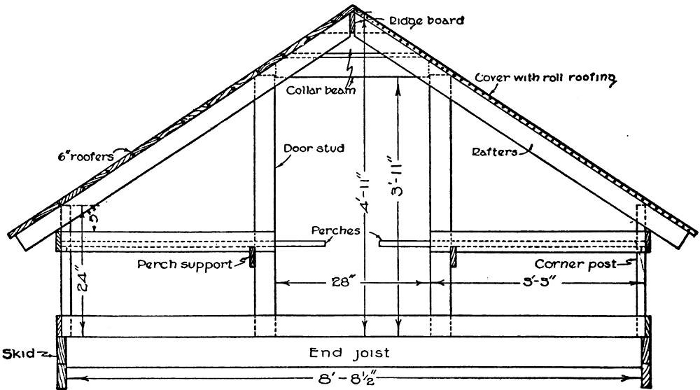

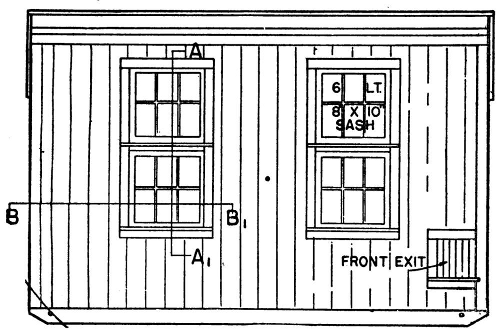

It isn’t always necessary to have expensive equipment to do a good job of raising poultry. It is necessary to have comfortable housing and equipment and to use all the ingenuity you have to develop easier and time-saving ways of caring for the birds without neglecting them in any way. Frequently, there will be an old barn on a homestead which can be remodeled into a chicken house several stories high. The main thing to keep in mind is that it doesn’t matter too much what size or shape the chicken house is, as long as it is well insulated and ventilated to keep the birds comfortable and as long as it provides about 3 1/2 to 4 sq. ft. of floor space per bird; one nest for every five birds; one foot of feed hopper space for every four birds; and about 8 or 10 inches of roosting space per bird.

Another reason why poultry raising can be profitable on a small acreage is that few poultrymen attempt to grow their own feed. Most poultrymen of any size now use a ready-mixed feed. They find this more economical in the long run and they usually get a better feed, for the reputable feed manufacturers are careful to analyze the ingredients which go into their feeds and to keep testing them to make sure that they are satisfactory.

Of course, there are several other ways to increase your income with chickens. If you have a good flock of birds, a local hatcheryman probably will pay you a good premium for eggs from your flock for hatching in the spring. Since this is the season when market egg prices are lowest, it can be a very substantial help in increasing your profit.

Then, too, you may find that you like breeding work and would like to hatch baby chicks for sale. Many of the best known breeders and hatcherymen today started in a small way, producing market eggs and poultry.

Sometimes you may find there is a special market for a certain product, such as small broilers to be served in halves, or larger meat birds, such as roasters or capons. If customers will pay a premium for these special products, they can be very profitable.

Under specially favorable conditions other branches of poultry keeping may be profitable but unless these conditions are assured they will almost certainly not pay. An ever increasing number of small farmers are specializing in turkeys. A generation ago turkey growing was a hazardous occupation. The dread disease black-head took a tremendous toll each year. But since modern science has discovered that the germ of this disease is transmitted through hen manure, a new technique of raising turkeys profitably has arisen.

It is possible, if one has very little land, to grow turkeys successfully from poults to marketing size without ever allowing the birds to go onto the soil. (Many of the larger growers follow this method also.) From the time the turkeys are allowed outside the brooder houses until ready for killing, they are kept on wire-floored porches.

Some successful growers keep the young birds on porches until they are about three months old and then put them on range until selling time. Turkeys are very susceptible to rain, cold, and drafts during the first few weeks after they are hatched. But once they get feathered, they are tremendously hardy and can roost on poles outdoors during the cold and rains of the autumn.

In the years ahead, it seems probable that more operators of small farms will turn to turkey raising as a main line of income. There are several good reasons for this. The initial outlay for brooders, brooder houses, and porches is not too great. A farmer can buy day-old poults from a reliable breeder and have them delivered when he wants them. This means, in effect, that if a farmer is going to specialize in turkey production, he will work hard for approximately six months of the year and can take life easier during the winter.

There are, of course, some turkey growers who will want to keep their own breeders. If a man builds up a reputation for vigorous, fast-growing stock, he can easily sell his surplus turkey eggs and poults. Good day-old poults sell for 50c to 75c each. A farmer who can sell from 1,000 to 3,000 poults a season can add very substantially to his income.

A fair question is: How much profit per bird can one figure on? The answer, of course, depends on a good many factors: cost of grain, overhead, market price, etc. But as a gauge the following figures may be useful.

It may cost in the neighborhood of $3.50 to raise a turkey from mid-April to November 20, including the price of the poult. If a farmer sells the turkeys at 15 pounds weight for 40c a pound, it gives a gross of $6, or about $2.50 profit per bird. Thus a man who raises 1,000 turkeys (about the right number for one man) would make a profit income of around $2,500. It is emphasized that these figures are only general ones. The writer knows small farmers who have sold dressed turkeys for years and never received less than 50c a pound. (A dressed turkey is one that is bled and plucked. When a turkey is sold, the weight includes the innards, head, and feet.)

One of the interesting developments in the years ahead will be evolution of a strain of broad-breasted turkeys that at maturity will weigh approximately 12 pounds. Good progress has already been made, both by government and state experiment stations and by private breeders. If a turkey strain is developed that fully matures around 12 pounds, it offers another opportunity to the man with a small farm. At that weight many families will buy turkeys off and on during the year, instead of only at holiday seasons. A farmer with a roadside stand could start broods of poults at different times from early spring until midsummer, and have dressed birds to sell during a major part of the year.

It is not necessary here to go into the technical details, but observation of successful turkey growers shows that certain methods and techniques lead to profitable operations. Neglect of these fundamentals means failure.

First, most commercial growers buy their poults at day-old and concentrate on getting the turkeys ready for the Thanksgiving Day trade. If a farmer is interested in keeping flocks of breeding turkeys, raising hatching eggs, and running incubators, he should not engage in the business on a large scale until he has had experience. Start at first with 20 or 30 hens and 2 or 3 toms. Best results in fertilizing of eggs come when from 10 to 15 hens are mated to one tom. The breeders kept through the winter will need a shed or part of a barn for protection during bad weather.

Second, while brooding operations are about the same as with ducks, the units must be smaller. A brooder house or room 12′ by 12′ or 12′ by 14′ should not have more than 150 poults, and 100 is better. Overcrowding is asking for trouble. All kinds of brooders are used: coal, oil, gas, wood, and electric. The right temperature for the first week is about 100º at the outside edge of the hover, two inches from the floor level. In brooding either poults or chicks a little too much heat is infinitely preferable to a lack of heat. When heat is insufficient, the poults pile together. Some are likely to smother; the birds on the inside get sweated. The poults “paste up,” contract colds, and “go off their feed.” There has been much loose talk about lower brooding temperatures. Within reason, plenty of heat is one of the best guarantees of brooding success.

Third, wire porches are essential, irrespective of what all-season system of growing is chosen. A wire porch about 12′ by 16′ on the south side of the brooder house will serve 100-150 young turkeys up to 3 months of age. Farmers vary in the way they build these porches. Commonly, 2′ by 4′ stock is used for cross-timbers, beveled at the top. At right angles across the 2 by 4’s, a good heavy wire, about No. 9 weight, is stretched at intervals of 4′ or 5′. Then the wire floor of 16-gauge size, one inch mesh, is stretched over the heavy wires and 2 by 4’s. This makes a firm, sturdy floor. The manure falls through the mesh to the ground. The porches should be about 3′ high and the sides and top covered with regular hen wire. On the small farm, the usual procedure is to raise the turkeys to maturity on the porches. If the grain hoppers and water pails are built into the sides of the porches, it greatly simplifies the work.

Fourth, most successful turkey raisers buy commercially mixed feeds, both the hard grains and the mashes. Baby poults are much slower than baby chicks in learning to eat. When the baby poults are put under the hover, place the mash before them in little piles on pieces of cardboard. It pays good dividends to work closely with the poults the first day or so and see that the youngsters are eating.

Fifth, on small farms where land is precious, it is the custom to raise the turkeys on wire right through the season. After the turkeys are 3 months old, allow at the rate of 6 square feet of sunporch and brooder house combined for each bird. Thus a brooder house 12′ by 12′, or 144 square feet and a porch 12′ by 16′ with 192 square feet, or a total of 336 square feet, would handle 56 turkeys until time to dress them off in November. If a small farmer is planning to make a living from turkeys, the wire-floored porch method is the only logical one, for when turkeys are raised on range, no more than 150 turkeys per acre should be allowed.

Sixth, it must be emphasized that the margin of profit per bird depends on the method of selling. If you can develop your own retail trade and have customers ready to pay the retail price, it can readily make from $1.50 to $1.75 difference in your profit per bird. The margin between wholesale and retail ranges anywhere from 10c to 13c per pound. When a man has a thousand 15-pound turkeys that represent his year’s income, this margin is a major factor.

An excellent bulletin for both beginners and experienced turkey growers is U. S. Department of Agriculture Farmers’ Bulletin 1409, Turkey Raising.

The presence of a lake or a river may lead you to think that duck and goose raising would be a good venture simply because these birds, being waterfowl, would forage for much of their food. But if you allow ducklings or goslings to swim there while they are small you may wonder what becomes of them until you perhaps see one pulled under water by a snapping turtle, a pike, or an otter, or some other voracious creature. My own small flock was reduced 75% in a mill race before I learned this fact! But I was only a boy then!

Commercial duck growing is a highly specialized business in which many single farms raise from 10,000 to 50,000 ducklings each season and place them on the market within 10 or 12 weeks of hatching. The only water these ducklings are allowed to have is what they drink. None but the breeding stock is allowed to swim.

Goose growing is not similarly specialized because, apparently, geese cannot be so closely confined but must have ample grass range on which to graze. Relatively small flocks are kept on pasture with no access to lake or river until the goslings are at least half grown, though they may have a small pond in which to swim.

Guinea fowls are the least tamable and most independent of all poultry. Once their wings are developed they will fly over anything—a barn, for instance! They largely take care of themselves and their young, are wonderful foragers, alert “watch dogs” giving alarm on the slightest suggestion of danger, and the young ones are delicious when they come to the table. Guineas are therefore in good demand at relatively high prices, but they must have free range, must be educated to feed at headquarters and to roost where they will be safe from prowlers.

Pigeons raised for squabs are also profitable when well managed but are often a nuisance because of the mess they make on roofs and walks. Like all other classes of poultry, except hens, they are for the specialist to keep—if the object is profit. For supplying the home table, however, a few pairs in a properly made cote should produce enough squabs to add a pleasing variety to the family menu.