The following information on bear hunting comes from Chapter 1 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

For many men, the grizzly bear is North America’s Number One big-game trophy. No other animal on the continent has a comparable combination of the sporting characteristics so dear to the heart of the big-game hunter. As a hunting prize, old Ursus horribilus stands alone.

There are many reasons why this is true. The grizzly has all the innate wariness, cunning, and elusiveness of lesser game. His habitat and distribution are sufficiently remote to challenge the hardiest hunter. Size alone places the grizzly bear in the top-most bracket of the big-game animals.

But in addition to these admirable qualities, the grizzly bear, and his off-shore cousin, the brownie, represent Americas only really dangerous game. The lesser species, from deer to elk, to moose and sheep, habitually try to escape during pursuit. The grizzly, oppositely, is just as apt to stand his ground, or “retreat forward.” He is a gentlemanly fighter, preferring to avoid trouble and be left alone. But the grizzly fears nothing, simply because no animal on the continent can lick him; and once into an encounter, a grizzly’s fight is to the death.

Legend, imagination, and exaggeration have all played their part in building the grizzly bear into a most awesome opponent. The rifles of the early settlers during the Westward movement were inadequate for the grizzly’s strength, courage, and ferocity. The outcome of any grizzly encounter was always highly speculative, and bear-maulings were frequent. Repeated re-telling of episodes wherein the hunter came off second best, added to man’s conception of the grizzly’s fighting potential. Gradually, a romance of bear hunting was built up; and there came to be a deep-seated urge in every rea-blooded male to kill a grizzly.

This urge remains today, strengthened by the dwindling opportunities of the hunter to meet dangerous game.

If I were to place one single characteristic which has made the grizzly our top American game, I would say it is his unpredictable nature. By constitution, pattern of living, and field behavior, a grizzly is apt to do certain things. Because of his hair-trigger temperament, he’s just as likely, and with but small reason, to do the opposite. No one can adequately predict a grizzly.

An indicative example, both of the grizzly’s unpredictable nature and the thrilling aspects of hunting him, occurred in connection with the biggest grizzly bear taken in Wyoming in recent years, and possibly on record.

Oddly enough, the encounter happened, not to a rugged he-man hunter, but to a tiny slip of lady weighing just over a hundred pounds.

Old Ben Taylor, who was born in the Rockies with cowboy boots on and who has been a professional guide and bear-hunter for thirty years, was guiding this spry little “dude,” Mrs. Dorothy Kircher. Dorothy was by no means a tenderfoot. She loved to hunt big-game, and had, previously, killed two separate elk while hunting with her husband, under Ben’s guidance.

Each fall, upon leaving elk-camp for home back east, Dorothy would say, “Ben, some year I’m coming out and hunt bear with you.”

Ben had a high regard for her spunk. “You come right ahead, and we’ll sure give it a try.”

So, during spring break-up in 1950, the Kirchers came back for Dorothy’s bear-hunt. Her husband elected not to hunt, largely to give Dorothy all the chances to “bust” a bear.

That spring, old Ben’s bear-camp was set up east and south of the wilderness Flagg Ranch. His time-tested method of bear-hunting was simplicity itself. As the blacks and browns and occasional grizzly broke from winter hibernation, Ben would strike off on webs with a small toboggan containing rations, a blanket, and emergency equipment. Once upon the fresh spoor in the snow, Ben never let up until the wandering bruin was his. Should nightfall interrupt, he slept by a fire under the shelter of a spruce. With a morning bite to eat, washed down with tea made of melted snow, he was at it again. Any bear which acted at all according to standard, didn’t have much of a chance; and today, Ben’s bear-hunting record in the Jackson Hole area is legendary.

So, at murky daylight one morning, Ben and the lady hunter struck off, with Dorothy insisting on pulling her share of the light toboggan on a single-tree. On the sled were the movie and still cameras, lunch, a coat or two and similar light gear. The plan was to hunt a circuitous route from camp, try to strike any fresh sign, follow it, and return to camp by dark. Dorothy had hopes of getting a black bear, sleek from hibernation, for a rug.

Near the head of Pilgrim Creek, however, that inexplicable form of “luck” so common to bear hunting changed the plan. By now, snow was falling and the makings of a full-blown spring blizzard were under way. But in the new snow, not an hour old, was fresh spoor. Not one, but four separate sets of tracks indicated that two adult grizzlies and their two yearlings were foraging for food to fill their long-hungry bellies. One track was huge.

Knowing such a trail was apt to lead for miles, and that the only chance was to overtake the beasts, Ben explained, then asked, “What would you like to do?”

“Let’s get him, of course!”

Briefly, they began what turned out to be twelve hours of hard plodding on snowshoes, dragging a toboggan in a blinding blizzard, before they finished that hunt. After three and one-half hours, they came to where a full-grown shiras moose had been dragged down by the bears, and largely devoured. “You never saw such a mess,” Ben told me recently. “About all that was left was hide and blood, strewn over the snow.”

By now the storm had obliterated their back-tracks. They had the bald choice of siwashing until the blizzard abated, or continuing the hunt. In all Ben’s extensive experience, he’d never observed any bear, after such a gorging, that didn’t lie down soon to sleep it off. With the encouraging prospect of soon coming upon their prize, they left the toboggan at the moose-kill and hurried on.

Then came another unpredictable aspect. The four beasts had not stopped to digest the fresh meat. Instead, they continued on, over into the head-waters of Lizard Creek. By now it appeared hopeless to trail them farther, but the lady wouldn’t quit. Weary and wet with the storm, they plodded on.

It was nearly three hours later before they came upon the bears. As in many a grizzly encounter, it came suddenly, and at a distance of around sixty yards. The spasmodic warmth of spring break-up had melted the snow deeply around the boles of the conifers where it was warmer, while leaving it crusted and thick in the open patches—making the entire country like some great white mattress, with the tufts embedded around the tree trunks. In one such “hole,” and on the wet pine needles beneath the tree, the family of bears were sleeping off their belly-aches—if the fitful rest of a grizzly can ever be called sleeping.

At the soft but audible swish-swish of the webs, the bears came to life. In great lumbering bounds, they shot, in four directions, up out of the hole. Two were half-grown yearlings. The biggest adult came out last.

Ben was mushing in the lead. All he saw in that blurred moment were some brown forms, quickly “evaporating.” “But knowing that spunky little dude,” he said, “I knowed somethin’ was goin’ happen fast. As the last bear came out into sight, I pitched forward on my knees and rammed my hands over my ears, so Dorothy could shoot over my head.”

Since they’d expected blacks, not grizzlies, the lady carried her .300 Savage.

“The first shot hit that monster just two inches from the tail,” Ben recalled. “Talk about a roar! You’ve never heard a blood-curdling sound till you’ve heard a grizzly bawl. It shook the country, and I figured Dorothy would go all to pieces. But she didn’t. Bruin went down at the shot, but was right up again. As fast as it would try to climb out of the hole, that gal would knock ‘im down again. In a lifetime of bear-hunting, I’ve never seen faster or better shooting. And by a woman, mind you! In four shots, she hit him twice. One went straight through that bear’s lungs—which did the business. It was over, just like that!”

There are additional and singular aspects about that bear, and which are still talked about with awe. Ben conservatively estimates the beast’s weight at “well over a thousand pounds,” and Ben is an honest man. Oddly, this bear was the sow, not the old boar which rightly should have been bigger. It was killed, nearly in its tracks, with a rifle and cartridge which most veteran bear-hunters consider puny—by a hundred-pound woman!

Till then, Dorothy Kircher had remained cool as the blizzard about her. They were a full eight miles from camp, with night coming on and their meandering back-track entirely blotted out. With the beast dead, Ben tried to lead Dorothy across a tiny creek on a big log, to temporary shelter. But the tiny gal, who could shoot it out with over a half-ton of enraged beast at a distance of yards, suddenly had weak knees. She simply couldn’t walk that log. Ben carried her across.

Old Ben’s knowledge of the country and his calm woodmanship finished up the affair most happily. Before dark, he managed to find a small patrol cabin known to be in the area, and succeeded in getting Dorothy and the toboggan to it, before final exhaustion.

An instance perhaps even more normal to grizzly behavior occurred to a Western guide some years back.

This veteran hunter-guide heart-shot a big silvertip under ideal conditions, and was certain he’d made a good job of it. He watched the beast topple, rise, run, and keel over again into the adjacent brush. Waiting ten minutes for the animal to die, this unfortunate man made the one allowable mistake of following too soon.

Days afterward, the searching party pieced the story of what had happened together, from the remains. The rifle-stock was broken off. The nickel-steel barrel was bent into a dizzy, obtuse angle. One single blow had caved in the man’s chest. The paced distance between the dead bear and the dead man was well over a rod. There was no spoor of either man or beast, between.

From this fact, the searching party had to conclude that the mortally-wounded beast had risen at close range, and come at the man, open-mouthed, in a death-struggle. Astounded, the luckless fellow had shoved his rifle cross-wise into the bear’s mouth. The beast’s remaining vitality had been spent in one terrible bite-and-blow.

Natives still marvel at that encounter, ending with the unanswerable questions: How many feet can a seven-hundred-pound bear knock a man with one blow? And, could a man with chest so caved in, rise to move any portion of the intervening distance, once struck to earth?

These are typical, though not necessarily singular instances of grizzly strength and behavior. The aggregate of such instances all combine to give a true picture of the grizzly’s great potential as a fighting antagonist and hunter’s trophy.

Physically, this great bear is an interesting animal. He is one of two species of ursines inhabiting continental North America—the other being the black bear, Eurarctos americanus. Adult grizzlies will run in weight from four or five hundred pounds, to a full half-ton or over. Two distinguishing characteristics are the pronounced “hump” above the withers of an adult bear, and the dish-faced appearance of the head. Coloration in grizzlies runs all the way from a creamy yellow, to nearly jet black.

As an example of this, one Wyoming grizzly I killed was a true yellow color, tapering quickly in darker shade to nearly-jet forelegs, and ivory-white claws. Another I took in British Columbia was virtually brown all over the body, with lighter, grizzled coloration of the face, and brown-black legs. A third was a true badgery color all over except for the pedal extremities. And only last fall I talked with a Yukon Territory guide who swore he had, for the last two years, seen a white grizzly. I have no reason to doubt the fellow’s word, as he appeared entirely honest, and talked with enthusiasm about the possibilities of bagging such a prize. On the other hand, it is also possible that the grizzly he saw as an albino may have been a pale yellow beast which appeared white—just as a creamy-white billy goat often appears pure white through the deceptive qualities of distance and sunlight on glossy pelage.

Regardless of the coloration, the guard-hairs along a grizzly’s spine are grizzled, or badgery-silver in color. This gives rise to his nickname, the “silvertip.”

Size and appearance both distinguish the grizzly’s tracks from those of the smaller black bear. A hind foot imprint left by a black bear, which measures four inches wide by six inches long, indicates a reasonably big blackie. The hind foot of one grizzly I killed near Cry Lake, British Columbia, measured eleven and one-quarter inches in length. This was a large beast, also measuring over a foot between the ear-tips. Large grizzlies, incidentally, have heads larger in proportion to their bodies than black bears, giving an extremely massive frontal appearance.

Another distinguishing feature of the grizzly’s tracks is the way the claw-marks set well out in front of the pad-spoor. The front claws of a big grizzly are nearly the length of a man’s fingers, and leave their imprint accordingly. Because of the mild curve of the claws, and the relative stiffness of the adult grizzly’s “wrists,” the mature bears cannot climb trees.

Grizzlies mate in alternate years, with the cubs being born in late January or early February while the female is still in hibernation. Grizzly cubs are often marked with white throat-patches. A grizzly sow will habitually “talk” with her off-spring, in a series of low growls, while on forays after food, or while teaching the young to hunt. There is no more ferocious beast than a female grizzly which has had her cubs threatened.

One of the basic factors which has made the grizzly America’s number one trophy, is the relative abundance of the great animals. As compared to deer and such lesser game, grizzlies aren’t numerous. There is, however, a sufficient population so that the average big-game hunter, who hopes and plans for the Big Hunt, can some day hope to bag one.

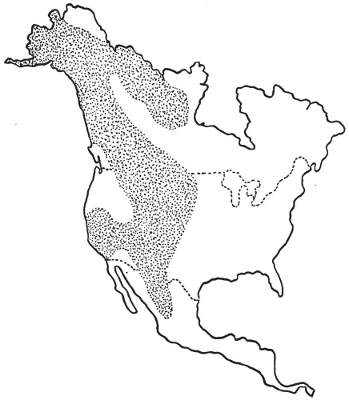

Most of the big bruins are located in Alaska and the bush country of British Columbia. In the United States, all remaining grizzlies are concentrated in the Rocky Mountains, with the exception of a few spilling eastward and westward, and over the border into Old Mexico. The last census showed a grizzly population of nearly fifteen hundred animals in the United States. Montana contains roughly half of these, with about five hundred animals being in Wyoming.

By nature, the grizzly is an individualist and wants to be left strictly alone. This characteristic, plus the gradual inroads of civilization, has driven him to the most rugged and remote areas left. In these wilderness areas, his range is extensive, and occasionally a grizzly will contact outlying ranches at the periphery of his range. Often grizzlies, when contacting domestic stock ranches, become killers of the first order.

A grizzly’s capacity for killing, and sheer physical strength in such encounters, are beyond the conception of the novice. A full-grown grizzly can, for example, break the neck of a two-year-old steer with a single swipe of his great paw.

One instance of a grizzly’s brute strength is indicative.

Some years ago, a Wyoming construction gang was building a road into a rugged section in the western end of the state. To keep pest-bears away from their meat supply, the men erected a tripod of lodge-pole pines, and derricked a fresh side of beef up under it. The half-steer was anchored to lengths of log-chain previously used for timber-snaking, and hoisted approximately ten feet off the ground—surely bear-proof.

Several mornings later, the meat was gone. The tripod was still standing. A hasty examination showed that the chain had been snapped, and there were some unusually large grizzly tracks beneath the derrick. Despite a thorough search, they could find no sign of the vanished beef.

Natives in the area are still asking questions about that affair. How, they ask, could a grizzly, that can’t climb, reach a height of ten feet? How could an animal, whose weight combined with that of the half-steer would nowhere approach the breaking-strength of the chain, succeed in breaking it? In my own boyhood, incidentally, I have often snaked firewood with similar, standard “log-chain.” Never, under the strain of a good span of draft horses, have I had one break.

Lastly, they ask, how could a single bear make off with half a beef without leaving a trace?

Many of the characteristics and facts of the grizzly bear could be applied to his larger cousin, the Alaska Brown Bear, if multiplied by two. Where exceptional grizzlies may run to eight or ten hundred pounds in weight, an outstanding brownie may reach sixteen hundred pounds and beyond. Like the grizzly, the brownie prefers a solitary hermit’s existence. Both species mate in June, have cubs every other year—which weigh only a few ounces at birth and are blind for approximately six weeks—and are most ferocious when with their young.

The one fact which excludes the brown bear from first place in the list of American trophies, is his relative scarcity and difficulty of access. Only the well-heeled sportsman who can afford to devote time and money to the project, can expect to bag a brownie.

The brown bear’s range begins on the coast side of British Columbia about mid-way to the north. From there the Pacific coast-line is the boundary, all the way up Alaska and the Alaska Peninsula. This crescent-shaped strip of range extends inward all along the coast-line of British Columbia, eastward into Yukon Territory, and Alaska. Numerous islands off Alaska, such as Kodiak, Unimak, Baronof, Chichagof, and Admiralty contain brownies.

Some areas, such as Kodiak and Chichagof, are noted for large specimens. The brownies in some areas, such as Admiralty Island, seem to run smaller. Several years ago I discussed this matter with Harry Sperling, forester of Juneau, Alaska. Mr. Sperling, incidentally helped make a brown bear census on Admiralty Island some years back.

In talking over a projected hunt, Mr. Sperling told me this:

“I can’t promise you any record brownie, if you hunt Admiralty Island. But you are pretty sure of a trophy of nine hundred pounds or so. And over the sights of a rifle, nine hundred pounds is a lot of bear!”