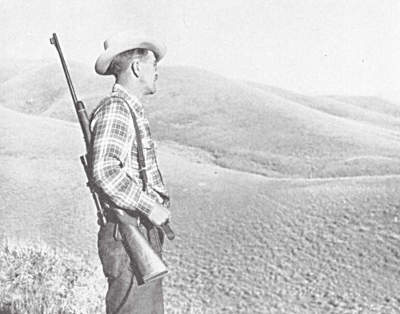

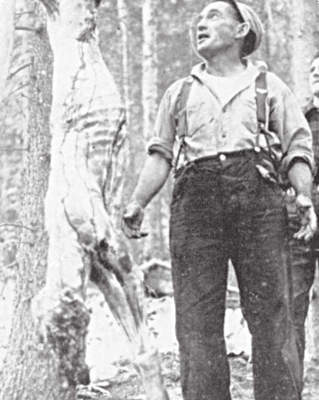

The following information on being a big game hunter comes from Chapter 16 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

The pursuit of our biggest game is not inexpensive as compared to other outdoor sports. This is increasingly true as the game herds dwindle, and the hunter must go to the more inaccessible regions to get his trophy. Transportation, outfitting, and capable personnel into, and in, such regions are all expensive.

Where the hunter lives within a big game area, knows his way around, and has his own outfit, he may still hunt those species native to his state or province with relatively little cost. But for the visiting hunter who must come into a region at a great distance, he simply cannot “get by” cheaply. Neither is it wise to shop about and accept the very cheapest in the way of outfitters, guides, and accommodations. As with anything else, the hunter usually gets what he pays for—this, so long as he deals with reputable people.

In spite of the relatively high cost of big game hunting, there is no waning of interest. Instead, as game becomes more scarce, the interest in hunting it proportionately is augmented.

There are in the United States over 15,000,000 licensed hunters. That means one hunter for each ten men, women, and children the nation over. The number of hunters has about doubled the past decade, with no visible signs of any trend towards reduction. Of this number, a large proportion are big game hunters. This is especially true of the western half of the nation. One has only to hunt each autumn in one of the western states to be convinced that the hunters are just above one hundred per cent of the total population.

In addition to the sporting aspects of hunting, there is an impressive commercial angle. The hunters of this country, Canada, and Mexico, together pour around $3,000,000,000 into the continent’s economy. That, any way you consider it, is big business; and as with any other big business, the basic trends and developments must be watched to save the stock-holders from ultimate exploitation. The big game hunter has a vital role in this.

To the non-hunter, the expenditure of considerable time, expense, and effort all towards the end of bagging a trophy for which there is no monetary value, appears silly. He can easily prove, on paper, that the pursuit of big game is not economically feasible; and to the person not experiencing the thrills of hunting and the allied joys of being in nature’s unexploited grandeur, that’s the end of it.

There is no need, however, either to try to explain the basic urge of hunting, or to defend it. Man’s urge to hunt animals has been handed down from generation to generation since the primitive ages. It is being transmitted today from this generation to our own sons and daughters. It will continue to be passed on, so long as there are people and anything to hunt. After the basic urges of hunger, sex, vanity, and fear of “ghosts,” hunting ranks among man’s greater passions.

What is the cost of big game hunting for our largest species?

The answer depends upon the species to be hunted; the distances involved, both from out and within the game region; the modes of transportation; the choice of outfitters; time to be spent; licenses and fees; and the question of residency.

Resident big game hunters are usually familiar with these costs, since they reside near the game regions. The non-resident hunter can gain an overall idea from spot, and typical examples of each item.

Beginning with transportation, the cost will depend upon the mode, which in turn depends upon the hunter’s available time. Where a party has the time and wishes to go together, the least expensive way is by auto, if the cost of the automobile is not considered. With the advent of the Alaska Highway—beginning at Dawson Creek, B.C. and running to Fairbanks, Alaska—most of the better big game country of the continent has been opened to car transportation. Regions not reached by car may be reached from road’s-end via airplanes.

Another method for the visiting hunter is to drive to the West Coast, and take a boat from Seattle, Washington, to points along the west coast of British Columbia and Alaska. From the coastline, short distances inland may then be completed via boat or plane. Many outfitters are bush-fliers.

There is regular bus service up the Alaska Highway, and it is possible now to traverse this entire route by passenger bus. The weight limits for baggage vary, but are usually generous enough to permit all personal gear in cases where the outfitter furnishes all accommodations.

For the hunter who is pressed for time, the chartered air-lines offer a fine method of travel. Distances are cut, over auto routes, and there are currently enough good air-fields near the best game regions to make this method feasible. Short hops into the bush with the outfitter’s pontoon-equipped plane usually complete this means of transportation, after the last stop on the air-lines has been reached. In such instances—and which, of course, have to be arranged well in advance—trophies are generally cared for by the outfitter, and later shipped via truck-express and/or boat back to the hunter’s taxidermist.

Just as an example, the cost of flying the air-lines from here at Rigby, Idaho, to Watson Lake in Yukon Territory is $133. The weight limit on duffel is 66 pounds, with a charge on excess weight.

Many well-heeled big game hunters have their own planes, making the transportation problem simple and ideal. One thing for pilots to remember in the north country is that many of the pocket-handkerchief, wilderness air-strips become increasingly souped-in with fog after September first. Delays because of this should be anticipated.

Airplanes, too, may be chartered by hunters where experienced and reputable pilots do the flying. Rates vary. Our own party has twice made Canadian and Yukon hunting trips using this means of transportation. The planes we used cost approximately thirty to fifty dollars per flying-hour, with the party furnishing all gasoline and service charges.

Often, for this kind of hunt, a pilot who wants to hunt, himself, will do the piloting free of charge, as his share of the cost.

Licenses and fees for the non-resident hunter vary from time to time, and should be checked for the current hunting season in advance. As examples giving a general indication, Wyoming and Montana charge the non-resident big game hunter $100 for a license. Wyoming has a special license for sheep and moose of $75, with a bear license costing $25. These are special fees, not requiring the $100 license in addition—this general license being for elk and deer, largely. Idaho charges the non-resident hunter $50 for a license for one big game animal. Additional species cost $25 each extra. An Idaho non-resident license for deer and elk, therefore, would cost $75 at this writing.

British Columbia licenses its non-resident hunters on a trophy-fee basis. A basic fee of $25 is charged, with additional fees for each trophy—$25 for moose, sheep, and grizzly. The hunter taking all three of these species would be charged $100, and so forth.

Since these items constantly vary, with the trend of each item consistently going up, the hunter should keep himself posted. In the matter of license fees, information will gladly be furnished the hunter from the game departments located at the capitals of each of the various states or provinces. The annual hunting regulations are ordinarily made up by May or June for the fall hunts, and the hunter should get his information shortly thereafter.

The most variable item of cost is, perhaps, the outfitter’s fee. While commercial outfitters are governed by the various game departments, there has been as yet no standardization of rates except on a broad gentleman’s-agreement basis. The only sure way of obtaining the existing rates, is to contact the outfitter.

Examples of fees current for 1956, and in widely-separated areas having a diverse set of conditions and accommodations, will give the visiting hunter a good general idea.

“Dal” Dalziel charges $100 per man per day for a big game hunt lasting a minimum of ten days. For hunts of thirty days duration, this fee is slightly reduced. Dalziel’s hunting country is some of the best on the continent for such species as Stone Sheep, grizzlies, goats, and caribou. Much of his country lies east of Dease Lake. Some of it has never been hunted by white men. Many of the lakes containing rainbow trout and Arctic grayling, have never been fished.

For this fee, the hunter is picked up at Watson Lake, Yukon Territory, after the hunter has arrived either via highway, or set down on the fine air-strip there. He is flown via pontoon-equipped planes to the hunting country and back to Watson Lake. All accommodations, guides, equipment, and food are furnished by the outfitter.

Tom Mould, operating out of Fort Nelson, British Columbia, charges a flat fee of $75 per day for the single hunter, and $50 per day per man for parties having more than one hunter. Tom’s hunting country is in the Liard River region, and everything is furnished, except the hunter’s personal gear and rifle, for the above fee.

In a section of Canada closer to the United States, Roy Seward, operating out of Golden, British Columbia, charges $35 per man per day, or $50 for two hunters, with a minimum of one week’s hunting time. This is on the Lake Louise route, reached by auto. Hunting there is for moose, grizzly, goat, and elk. Visiting hunters are put up at Seward’s lodge, with the actual hunting done on short expeditions on foot from the lodge itself.

Don Smith, who has outfitted for years on the famed River Of No Return in Idaho’s Salmon country, charges $400 per man for a week’s hunt, for a party of four. This hunt is for elk, deer, and black bear, including hunters who have drawn on the special hunts for goat and/or sheep. Don picks the hunters up at his lodge at North Fork, Idaho, and floats them through for nearly one hundred miles to the tiny sawmill town of Riggins, down-river. Everything is furnished on these trips, except personal gear. The hunters’ car is hauled around to Riggins on the big truck-trailer which is driven around to pick up the big boat for the return trip back to North Fork.

In the famed Chamberlain Basin country of central Idaho, the hunting area is reached mainly by air. Hunters leave their cars at McCall, Idaho. Vern Hamilton, who operates in this region, has an arrangement with Johnson Flying Service to fly hunters to the Chamberlain air-strip for $33 per man, with a maximum of sixty pounds of duffel per man. Additional duffel, and meat coming out, is charged for at the rate of four cents per pound.

At the wilderness strip, Hamilton meets the party, hauls them to his hunting lodge, and then packs them into good hunting areas with a pack-string, and out again with their meat and trophies—this for a flat fee of $75 per man.

In some of the best hunting in western Wyoming, “Sandy” Sanders charges a fee of $350 per man for a one-weeks’ hunt. Hunters are met at Jackson, Wyoming, either at the air-port or the outfitter’s home, taken to Turpin Meadows, to the big base-camp, and then to the hunting area on saddle-horses. This outfitter hunts the Yellowstone River-Thorofare area, some of the most primitive left in Wyoming. Hunting there is mainly for elk and deer. Hunters having drawn lucky permits on moose and sheep are also accommodated. Everything except personal gear and rifles are furnished on these hunts.

These are typical examples of the fees of the best outfitters catering to the visiting hunter. Such fees, of course, are subject to the changes which occur with a fluctuating economy. But they may be regarded as average among the topflight outfitters. Too, there is an effort among these men, whose business depends to a great extent upon the repeat business of a satisfied clientele, to standardize the rates. That is, they wish in so far as possible to have their future rates as near as possible to existing fees.

I have personally been on hunting expeditions with all the above outfitters with the exception of Roy Seward, and a hunt is in the making with him. While being hosted by such a variety of outfitters, over such an extended scope of hunting country, I have become closely acquainted with the problems and relatively high costs of outfitting. For the increasingly short hunting seasons, the outfitters must, I am convinced, charge such fees to remain in business.

As with any other business, there are those who charge less. Often they capitalize on the reputations, advertising, and hunting areas of the reputable outfitters. Packer’s associations, sportsmen’s groups, and various fish and game departments are all trying to weed out the chiselers, and make outfitters adhere to a minimum standard of equipment and performance. Great strides have been made the past decade towards this end. As with other businesses, the outfitter’s best advertising is a satisfied customer; and the recommendation of such a satisfied customer is the hunter’s very best guide in choosing his outfitter.

What is the future of big game hunting?

The overall picture is one of diminishing opportunity. True, the senseless slaughter of some of our big game at the turn of the century, and which caused virtual extinction in some cases, has been stopped. This has been done by legislation, conservation, and the co-operation of sportsmen and land-owners on whose properties some of the game lives. Today there are many game sanctuaries and refuges set aside in which remaining herds may be perpetuated.

Despite this, the wild-game populations will decrease. Hunting pressure will increase as the population increases, and as the continent becomes more urbanized and man’s need for getting away from it all correspondingly grows. The demands of an agrarian economy will cause a constant gnawing away at the remaining game habitat and ranges.

Big game is a crop. Unfortunately, it is not a crop which can be saved or stored. Rather, it is a fluid crop whose only use lies in its utilization. If game is not hunter-harvested, it will ultimately become lost to disease, predation, extremes of weather, and old-age.

The sportsman-hunter who has enjoyed the high privilege of hunting, himself has the basic obligation of passing on this right and opportunity to the next generations. He can best do this by personally helping to set up the machinery for the perpetuation of the remaining big game. His personal goal, and the collective aim, should be that of perpetuating the species, and spreading the harvesting of the surpluses or increase where it will do the most good for the greatest number—both at present and for the generations to come.

Since big game ranges, especially winter ranges, are the deciding factor, this often as not means not only the further restricting of hunter-harvest; it often means the increased harvesting of game whose range are over-utilized. It is poor overall economy for the over-zealous hunter for example, to rise in his sportsmen-club meeting and, thinking he is “saving” big game hunting a bit, vote to restrict game-hunting in a certain area, and then have the entire herd decimated the following winter by extreme weather and an over-grazed range. It seems equally foolish to the overall objective for the big game hunter to take to the field without first equipping himself with sufficient hunting skill and ordnance so that he won’t cripple one big game animal for every one he ultimately brings to bag—this ratio being an even optimistic estimate. The time has long passed when we can experiment upon our remaining big game animals.

Conservation, and the ecology of big game, are relatively new fields of study. We don’t know all the answers to the big game problem, or to the future of big game hunting. The role of the sportsman-hunter can be a vital one in proportion to the extent he concerns himself and makes his influence felt in the important matter of assuring the next generations the continuing sport of big game hunting. His responsibility in this should be the price he is willing to pay for his own current joys of hunting.

In conclusion, may I humbly say that the satisfactions of big game hunting are many, varied, and often as deep as they are intangible. They more than off-set the cost, the time, and the necessary effort. No man who hunts big game on a high sporting level, according his quarry the same sporting chances he’d ask for himself, can but become a better human through having had the experience.

Pete Bradbury once summed it up rather well, after we’d been on a big game hunt together. Pete is something of a philosopher, and is sufficiently well-heeled so that he may do what he wishes, among company he likes.

“Do you know,” he asked, “why I associate myself with big game hunters?”

“Why?”

“I have never yet met a big game hunter that played the game according to the rules, who wasn’t a pretty good human in all other respects. I just like to be around ’em.”

This is a sobering compliment.