The following information on hunting bull elk comes from Chapter 7 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

The elk, or wapiti, is for many a big-game hunter the best game animal. This is due to a number of reasons, based upon red-blooded man’s hunting instinct.

First, an elk hunted under today’s hunting pressure is one of the most challenging trophies. He is spooky by nature. He inhabits the last remaining wilderness areas, and plays his game of wits with the hunter in the roughest terrain. A mature bull elk is, pound for pound, one of the toughest game animals in North America to kill. In the timbered country he now habitually inhabits, he can, when hunted, move with less noise or disclosing of his great body, than any animal of comparable proportions.

Coupled to these appealing and challenging qualities is the fact that his numbers today are still sufficient so that the average big-game hunter can bag one. More, an elk-hunt is relatively inexpensive—as compared to sheep-hunting and grizzly-hunting in good areas—and the trophy is most imposing. Lastly, there is no better game meat than steaks from a good elk, unless it is from a young mountain sheep; and a pair of elk-tusks—fine mementos of the hunt themselves, and occurring in both sexes—represents the only true ivory of continental United States.

I have hunted all species of North American big-game. I still maintain that an elk-hunt is one of the very best hunts. Numerous big-game hunters readily agree.

The history of the American wapiti, Cervus canadensis, is a most interesting one. The elk was not always the high-country, wilderness animal he is today. Instead, he was once a plains animal, roaming most of the United States and southern parts of Canada. Unlike members of the deer family, the elk could not stand civilization. He was unduly slaughtered for his fine food and usable hide. In many instances he was lamentably killed solely for his ivory tusks—a pair of which appears on the opposing sides of the upper jaw of adult animals.

These tusks were made up into old-fashioned watch-fobs, stick-pins, and the dangling ornaments for the gold watch-chains of Grandpa’s heyday. A fad was started and grew to outlandish proportions. Every man worthy of the name wanted a set of “elk-teeth.” If he couldn’t kill his own elk, he was willing to purchase the tusks.

The result was that the obtaining of elk-tusks became commercial. As recently as my own youth, a good pair of elk-tusks would bring from twenty-five to seventy-five dollars. I have talked with old-time Wyoming residents who told of riders roping dozens of elk caught in winter snows, pulling their teeth, and letting them go again. Others simply slaughtered the fine big animals to get their teeth, and left them lie.

Eventually ranchers, sportsmen, and other thinking people all helped put a stop to this sickening condition. They effected legislation prohibiting the sale of elk-teeth. This, coupled to the gradually stiffening game restrictions, put an end to that form of slaughter.

The desire for a pair of good elk-tusks, however, still persists. In 1946, after I’d killed a Montana bull having exceptional ivory, another hunter found the quarters and trophy while it was cooling out. He didn’t molest anything except to steal the teeth.

And only last fall, I had occasion to re-pay the kindness of a South Dakota host who had long wanted a set of elk-teeth, by sending him a pair I’d taken a month previously, from a fine Idaho bull.

The wholesale slaughtering of elk a century ago, decimated the bands. Invading agriculture took a heavy toll of the large areas of range needed by this large animal. The remaining elk were, like the pronghorn antelope, threatened with extinction. They left their plains habitat, and gradually took to the higher wilderness country. There the great animals found virgin ranges, freedom from molestation from their greatest enemy, man, and competition from other browsing animals.

It is in these remaining rugged areas that our elk population is found today. With no other big-game animal has there been more of a shift as to elevation and range, or an acquired conditioning to the needs of existence. This tendency towards mass migration still persists in the animals today. They shift with the changes of season from the crags of goat and sheep country in the summer, to the low flat farm-lands at the periphery of mountain country for winter. This, largely to follow the food supply.

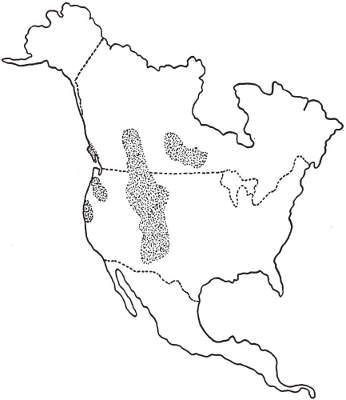

Again, as with the pronghorn, man’s vision and enactment of stringent game-laws not only saved the wapiti from extinction, but permitted the animals to increase to shootable proportions in many areas where they had been decimated. For example, from the period of the Civil War to near the turn of the century, the elk was progressively exterminated from the East, the central plains, and the Southwest. Today, there are well over a quarter-million of the great animals, spread over exactly one-half of the states of the Union. In areas of the Rocky Mountains, they have propagated their kind on their own. In decimated areas, they have been replanted and are taking hold.

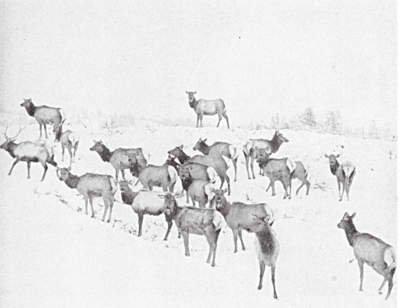

It is interesting to note, incidentally, that the elk in their greatest sanctuary, Yellowstone Park, are, at this writing (1956) overpopulating their ranges by a ratio of nearly three to one. Winter range is the criterion, as with other species, and there they have become an acute problem. Efforts are being made to live-trap and transplant the animals into the hunting districts of surrounding Northwestern states, so that the hunters may harvest the surplus. In instances of approaching and certain starvation, some of the animals are killed and given to charity.

This is but a localized, “spot” problem. But it does indicate a condition and a trend which can carry over into hunting areas of limited winter-range, utilized by a migratory and concentrated game-herd. The general policy of the various game commissions is to allow the animals to reach a near-capacity of their winter ranges, allowing a margin for extremes of weather and season, then to hunter-harvest the surplus, or annual increase. Elk will increase, after disease and predation, on an average of around fifteen to twenty per cent.

As to distribution, the majority of today’s elk-bands are located along an extended belt running generally north and south, and co-incident with the Rocky Mountains. This area extends from nearly to the Texas-New Mexico border on the south, to mid-way of Alberta, northward. Other large areas of localized elk-populations are along the Pacific Coast in Washington, Oregon, northern California, and up the coast-line into British Columbia. There are also minor elk-populations such as in the Muskwa district of British Columbia.

As to concentration, the states of Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, and Idaho, have the largest numbers, and in that order.

Population alone does not determine the choice districts in which to hunt elk. Remoteness, accessibility, available of pack-stock, type of terrain and cover, ratio of the population to extent of range, and hunting pressure all have a vital bearing on the hunters success. Too, there are the important matters of length-of-seasons in relation to the game-bands, and whether the hunt is general, or restricted to drawing-and-permits. The hunter coming into an area should consider all these factors before deciding.

From personal experience, I would put such areas as Idaho’s Lochsa-Selway region, the Salmon River country, Wyoming’s Jackson Hole area, the Bitter Root and Sun River regions of Montana, and Colorado, as the choice elk-hunting areas.

Examples indicative of this are the fact that annually from 12,000 to 15,000 elk are winter-fed at the Jackson Hole Elk Refuge, and the annual elk-kill of the Selway-Lochsa area runs approximately 5,000 animals. These two examples also indicate the annual cycle of the great animals. The Selway-Lochsa herd is non-migratory in that the bands simply move down to their winter ranges, which are within the vast wilderness region itself. Conversely, the Jackson Hole elk-band represents an aggregate collection of gradually-drifting animals from the Yellowstone Park fringe, Thorofare, Yellowstone River, and Buffalo River drainages. These animals have a well-defined pattern of migration covering forty miles—from the head of the Yellowstone River, to the Buffalo, to Box Creek, Turpin Meadows, and thereafter straight for the refuge—another instance of sheer animal-conditioning.

Wyoming’s Grey’s River area has a similar annual elk-drift, to the winter range and feeding-grounds near Alpine. Idaho’s Ashton-Island Park country has a similar, annual migration of animals from the Yellowstone periphery, to the winter range along the lower reaches of the North Fork of the Snake River still within the timber-belt.

A broad but true generality is that the resident elk-hunter hunts for meat and sport, but the non-resident hunter hunts for a trophy. Even with the resident hunter, the gradual trend is toward sport-hunting, rather than for meat. Public sentiment has a direct bearing on this. As one sample, the resident hunters in Wyoming who catch the drift of animals moving towards Jackson Hole, and kill only for meat, are referred to even by their neighbors as the “gut hunters.”

What is a good elk-trophy?

Next to the antlers of the moose, the elk has the most massive head-gear of any American game. An adult bull elk’s antlers may reach from four to five feet above his head. Further, the elk holds his head at a higher angle than does a bull moose, and his antlers also rise more vertically—all creating a most imposing trophy and subsequent mount.

As with other antlered game, the number of points increase, to a certain extent, with the annual age. A spike bull may be a two-year-old. The next season he may have antlers forked into a three-pointer. This continues until the adult bull may have five, six, seven, or rarely, eight points to the antler. The bulls are in their sexual prime at four to eight years, and, as with deer, there is a direct relationship between sexual vigor and antler-size. When the bulls begin to go downhill, their antlers become more scrawny and smaller. The massive head-gear is shed each season, from February to early April depending upon elevation and severity of season; and a new growth is made, as with deer and moose.

It is axiomatic that in elk-hunting one finds the largest heads upon the bulls able to service and hold the greatest number of cows. The wapiti is the most polygamistic-minded of American big-game. A big herd-bull’s harem may include from a half-dozen to thirty or more cows. These he holds during the rut with sheer force, against the invasion of lesser bulls. The smaller whipped bulls generally are those with the smaller head-gear. Where the hunter finds such a bull, alone, whipped from a band and on the make, he can be sure that the trophy likely isn’t anything exceptional.

The tines, or points of an elk-antler all come out from a single massive beam, with the exception of the fourth point up from the head. At this point, the beam almost bi-furcates, forming the “royal” point. Beginning at the head, the first point above is the “brow” point; the next the “bez” point; and the third, the “trez” point.

The “standard” full-grown bull has a total of six points to the antler. Such a bull is referred to in the West as a “royal bull.”

Since a mounted elk-head rears to such a height, as compared to moose, even trophy-hunters often desire such factors as perfect symmetry, and “ivory-tipping” of points, above sheer size. One of the nicest elk-trophies I’ve ever seen was a perfect six-pointer which didn’t exceed three feet in antler-spread. Its owner had hunted an entire week, turning down far larger heads until he got just the size he wanted for his den.

If one hunts for the exceptional trophy, or “braggin’ meat,” he should be familiar with the measurements of the best heads. At this writing, elk have been taken whose inside-spread of antlers exceeds five feet. Other heads have antler-lengths also exceeding five feet. Antlers have also been taken whose circumferences, at a point between the brown and bez points, exceed 12 inches.

As to animal-size, some of the big bulls will weigh up to 1,000 pounds and over. I have killed Selway bulls whose skinned and trimmed quarters weighed up to 137 pounds average, at the home cold-storage plant. These quarters, further, had the legs removed; and the front pair had been cut off short at the shoulder-line—no packer will pack out an elk-neck if he can get out of it. Bull elk so dressed, and with the cape, head, and neck removed, will dress off at least fifty per cent.

Cow elk are proportionately smaller. A cow weighing 600 pounds is a large cow.

How does the hunter ascertain, before he pulls the trigger on his prize, just how big the antlers are?

Sizing up a trophy during the heat of hunter-excitement just preceding the shot, takes experience, will power, and cold appraisal. This is especially true if the only opportunity for a shot is a quick one. The problem is further complicated by the fact that while, broadly speaking, the massive antlers go on the largest bulls, this is not always true—due principally to the effect of age and sexual vigor, and its relationship to antler-size.

One of the best ways I’ve ever found for sizing up a trophy elk in advance of the shot, is by a comparison of sizes as between different animals of a band, and the comparison of antler-size to animal-size in the intended trophy.

If a bull is with a band of cows, the largest cow should weigh nearly 600 pounds. If the bull appears, in a quick glance, to be approximately twice the size, he’s a whopper indeed. If, on the other hand, the bull seems only slightly larger than such a cow, yet his antler-size is large in proportion to his body, then he’s still apt to be a small one with antlers past the prime, or a young bull.

Again, if by comparison with other animals appearing with the bull, he definitely appears to be large, then a reasonably accurate estimate of his antlers can be had, assuming there is a few seconds of time. A mature bull elk will stand almost five feet high at both the withers and at the hips. The rectangular “block” of his body, as seen broadside, will reach nearly four feet from the shoulder-line to the sun-flower of his rump. More, the vertical height of his neck, just back of the brown mane against the shoulder, will be right at two feet. Lastly, a bull elk’s belly-line will be just about the height of a kitchen table off the ground, unless he’s mired in—thirty inches.

Comparison may be made against these measurements, which may be easily memorized in advance of the hunt. For example, if, as the bull grazes or noses the ground, his antlers appear to reach to the height of his withers, he’s well into the trophy class. Or, if his antlers appear to be twice as great in length as his neck is deep at the shoulder, then they’re close to five feet. Again, if, from a normally-standing position, the tips of a bull elk’s antlers appear to reach one-third the way back along his spine, then he’s a big one. Similar comparisons can be quickly made, as to antler-spread, when the beast turns head-on, or angling away.

Such comparisons, if the hunter will force himself to make them, will surely prevent the killing of small young bulls, at least, for what the excited hunter firmly believes to be record heads.

With elk, many hunters hunt for the meat as well as for the sport and the trophy. To some degree, the quality of elk-steak can be determined on the hoof. Meat depends upon animal-condition, which in turn is reflected in the coloration. Age also shows in the animal’s coloration and character of the hair. Long or scraggly hair on an elk during fall hunting season means a poor animal. And, broadly speaking, a sleek, round animal, dark in color and nearly jet black down the haunches between the animal’s side and the “sun-flower” indicates a fat young animal. If a bull has aged to where he is a light, tawny, cream-color like a straw-stack, and especially if his back muscles have begun to recede down away from his spine, there is a good possibility that he may be a “scabby” bull. Scabby bulls are those afflicted with mange, and conservation officials usually kill them and burn the carcasses whenever they are found. This prevents the spread of the disease.

However, even if such a bull isn’t mangy, he may be a wonderful wall-trophy, but you won’t be able to stick a fork in his gravy.