The following information on Canadian moose, Alaska moose, and Shiras moose hunting comes from Chapter 4 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

For sheer weight and trophy-size, the bull moose is North America’s top big-game animal. Individual animals will weigh from 1,000 pounds up to nearly a ton for the Alaska species.

The hunter who hasn’t yet taken moose has a thrill in store for him in this respect, and I well recall a humorous instance exemplifying the average person’s mis-conception.

On a recent Canadian trip, four of us went via chartered plane. Since weight and space were at a premium, we decided in advance that the trophies should be more or less rationed—at least that only one hunter should bring back a moose. One of the party was a natural for this species. He’d just bought a fine new home having a large mantel over the fire-place. The evening before we left, his pretty wife Rudy suggested, “Gordy, why don’t you take the moose? I’ve always wanted a moose head, and his horns would fit perfectly there above the fire-place.”

So we agreed to let Gordy take the moose.

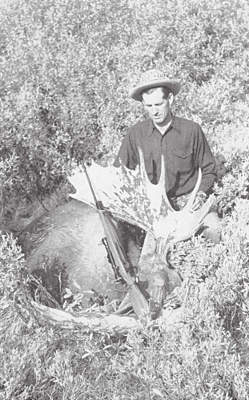

The bull he bagged along the shore of Rainbow Lake measured fifty-inches-plus in spread. The antlers had a total of twenty-three points. The head, measured from medulla over the forehead and to the nose-tip, was a full thirty-three inches. From the tip of the withers down the shoulder and to the point of the front hoof measured close to seven feet. The bull’s fresh tracks in the shore-mud, photographed alongside my own bare foot for comparison, was nearly as long. We flew out nearly six hundred pounds of boned meat.

When we arrived home, Rudy was at the air-port to meet us. As we twisted and lugged that monstrous antlers-and-cape from the fuselage, she suddenly began laughing. She laughed until the tears ran down her lovely face, abruptly envisioning Gordy’s “trophy” over the home mantel.

“What’s wrong?” I asked her.

“My God!” she exploded, irreverently, pointing at the prodigious head, “don’t you want half of it?”

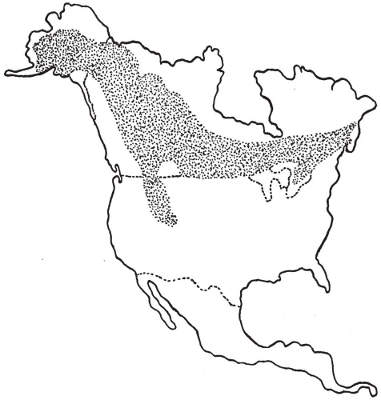

North America’s moose are divided into three major species. Those inhabiting the Rocky Mountains of the Northwest are Shiras, or Wyoming moose—Alces americana shirasi. The vastly larger numbers in Canada are of the species Alces americana americana, or simply Canadian moose. Those in the Kenai Peninsula of Alaska and northern Yukon are the Alces gigas, or Alaska moose.

The principal difference among the three species is that of size. The size of North American moose increases as the species are found northward.

Shiras moose, the smallest species, may reach an overall weight of up to 1200 pounds for adult, mature bulls. A specimen of this species with antler-spread of four feet is considered good. For many years the record head had a spread of 54 inches.

With the Canadian moose, it takes an antler-spread of at least one foot more to be comparable. Bull Canadian moose may weigh up to 1400 pounds for exceptional animals. The record head for this species exceeds a full six feet in antler-spread.

The Alaska moose is the largest of the lot. Individual, exceptional bulls may reach a weight of 1800 pounds and over, though often this weight is estimated. The facilities for weighing an undismembered bull moose, as for weighing a grizzly, are sketchy in bush country. The head-gear of the Alaska moose is tremendous. The record head, as to antler-spread, measures well over six feet.

The history of the moose population and movement of the species in North America is an interesting one. This animal is the largest of the American deer, and requires a combination of cold climates and timbered terrain for existence and propagation. Although the species is relatively non-migratory in annual habit, the entire populations have gradually moved northward.

With the increase of the pressures of civilization, and the cutting down of the forested areas in the Northeastern states, the moose moved northward and westward. Legislation put a stop to the wanton killing of the big animals for meat, hides, and sport, coincident with the coming of the white settlers. But this came too late to save the moose from near-extinction in the northern-most tier of eastern states. The animals retreated into Canada.

In the western states, the picture was brighter. The moose in the states of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho gradually increased in numbers—this due in a large measure to the rough terrain of the Rocky Mountains, rendering the habitat unsuited to agriculture. Idaho had its first legal season on bull moose in 1946, and has had an increasing number of permits issued every year since. Wyoming and Montana, likewise, have had increasing moose populations.

In Canada, the moose-range is most extensive and the populations great. Every Canadian province has moose. The animal’s range extends northward from the United States border to a general sweeping, crescent-shaped line coinciding with the northern fringe of the timber-belt. The largest moose populations are found in the western half of this area.

The animal’s entry into Alaska and the Yukon is more recent, and the populations are increasing there.

In addition to the migration caused by the inroads of an agricultural economy, there are other causes for this mass movement of a species. Some attribute the shift northward to the vast forest fires with which Canada has been plagued in the last century. Certainly the second-growth gradually appearing in these burned-over areas is ideal moose food and cover.

Another reason for an increase in moose population in spot areas is the control of wolves. Dal Dalziel has made a study of this in the Dease Lake section of Canada and in the southern Yukon. There the natives and visiting sportsmen have made a constant war on the big predators—the most productive way of killing the wolves being to hunt them in winter on the ice of lakes, from a low-flying plane. The wolves in these areas have been controlled to the point where relatively few are left. The moose population has increased in direct proportion to the wolves’ dwindling numbers.

Whatever the combination of reasons for the moose’s northward shifting, and increase in the bush country, the net result is obvious for the big-game hunter. His best chances for success are in Canada. There the numbers are sufficient so that, under the guidance of a good outfitter, the visiting hunter is almost assured of a good trophy. Should he desire the very largest, his best bet is in Alaska or the Yukon.

If the hunter is content with a trophy of the smaller Shiras species, and if he wishes to combine his moose-hunting with the hunting of other large species such as elk and bear, then the Northwest, within the United States, offers good hunting. The hunting here, unlike the long open seasons of most Canadian provinces, is on a limited, controlled basis. Permits for a moose from a certain defined area are drawn by lot from the number of applicants. The “lucky” hunters are almost assured of a trophy, since the annual harvest takes no more than the increase of a game herd having reached the near carrying-capacity of its range.

Wyoming is a typical example. Annually, this state reserves three-fourths of its moose permits for resident hunters. The remaining fourth of the permits are open to application from nonresident hunters. The number of adult animals to be taken from any area is specified. For the year 1955, the total number of moose to be taken was approximately 700 head of mature animals. Residents may kill either sex. Non-residents may take only mature bulls.

The moose is, in appearance, the oddest of our big big-game. His great hulk is put together something like a falling tear-drop, with the majority of weight and shape at the forward end. The massive, palmated antlers, meant for the battling of the rut, are heavier than on any other American game animal. They are supported by a prodigious head and neck, the head ending in a long “Roman” nose, monstrous in itself and terminating in a huge overhanging lip. Beneath the lower jaw hangs a hairy skin-and-hide appendage called the “bell.” This bell often reaches a length of two feet or more.

The great neck tapers into high-withered shoulders which are out of proportion to the overall animal-size. From the great hump of the shoulders, the body tapers swiftly towards smaller hindquarters and an insignificant little knot of tail.

The beast’s legs are long and gangly—perfect for fast moving over down timber and for wading in lakes and rivers. The huge splayed hoofs, likewise, are meant for supporting the animal’s great weight in the mud, muskeg, and bogs common to moose habitat.

Such incongruous features as the over-hanging upper lip and the bell have functions, also. With the moose’s flexible big lip, he can strip leaves and tender twigs from aspen trees most dexterously, just as he can take hold of the under-water vegetation common to his diet. To most people, the bell is of no earthly use. My friend Carl Reimann offers the most logical reason. Carl has a vast cattle-ranch in the Ashton, Idaho country, near the periphery of Yellowstone Park. Moose live on his ranch the year round. And though this man has never killed one of the ungainly animals, nor does he have any desire to, he has, nevertheless, spent a lifetime in studying them. “As near as I can figure,” Carl says, “a moose’s bell is simply to drain the water off his face, after he lifts his head from the water. It keeps the water from running back down his neck.”

The moose varies in color with the seasons and species. Normally, his coat is a brown-black, with lighter colored brown-gray on the face. Young bulls are normally darker in color than the older animals. Young Shiras moose are often nearly black on the haunches, with the color washing out into a roan-white down the hind legs. At great distances, moose habitually appear as black objects, due to the contrast of color against surrounding lighter-colored foliage, grasslands, and water.

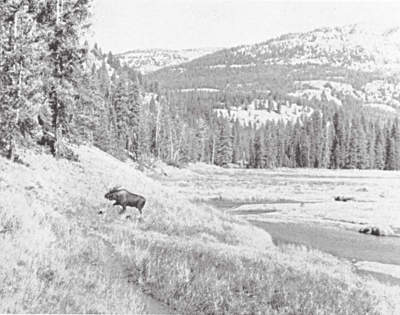

Though the great animals need a timbered terrain for their range, they spend a big share of their lives in and near water. The shallow shore-line of lakes is a favored spot for feeding. So are the meadow-lands through which streams flow. So are swamps and bog areas interspersed in timber-lands.

The animal’s pattern of daily living in such areas is constant during the summer and fall months. They feed in the open meadows and at water’s-edge at daylight and again at dusk. With the appearance of the morning sun, they gradually move back to surrounding timber. There, on the mild plateaus and benches adjacent, they shade up for the day, protected by the dark foliage and away from flies. About an hour before dark, they move out of the timber again to feed.

In Wyoming’s Thorofare country, I have watched as many as a half-dozen of the big animals feeding in Bridger Lake, unconcerned about my appearance as I fished for cutthroats. Some of the beasts would be submerged except for a thin line of withers. Then suddenly the great head would appear, dripping streams of water, and with the big silly-looking mouth full of aquatic vegetation.

Similarly, from a camp on Atlantic Creek, I have, with binoculars, for days on end, counted up to a dozen of the monstrous beasts feeding in the Yellowstone Meadows at daylight and again at dusk. During the long hours of the day, the meadows would be innocent of game. But with dusk and daylight, the big animals would be there.

The rut is co-incidental with the hunting season, and at the onset of the mating season, a change comes over the bulls. They become pugnacious. They begin grunting—a challenge comparable to a bull elk’s bugling—and travel more. In Canada the period of the rut begins around September the 5th. Thereafter the bulls are at their best as trophies, with the velvet rubbed from their antlers and ready for battle. Like “running” bull elk, bull moose at this period literally stink, from the musky odor of their urine. Both species delight in rolling in mud-holes and wallows, in which they seem constantly to urinate. As Sandy Sanders, an outfitter in the West puts it, “I know of no other beasts that can drink a quart of water and expel five gallons.”

During the rut, the bulls often lose all fear of man. They become pugnacious and will charge a man or horse. This, as with other species, is induced by the craze surrounding the rut. With a moose, I cannot help thinking that some of his apparent semi-stupidity is due also to the small size of his brain. In a trophy Shiras bull I killed in 1955, which will undoubtedly rank among the records, the entire brain was but little larger than a large doubled fist. This, in a bull estimated at 1200 pounds.

This disproportionate size as compared to other species may account for his relative lack of wits, as compared to other big-game animals.