The following information on Dall Sheep, Stone Sheep, and Bighorn Sheep comes from Chapter 14 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

To many men, a trophy ram represents the ultimate objective of their hunting experience. Other species they regard as lesser, and, secretly, as but hunting practice for the Great Day when, somehow, they will be able to go into wilderness country after a sheep.

Weldon Alldredge was such a man. He was a hunter by nature, and a gun-crank by hobby. Like the majority of men, the responsibilities of marriage and making a living occupied most of his time and effort. By profession, Weldon was a commercial pilot and a good one. In his spare time, he played around with his wildcat rifles, learned how to shoot extremely well, and found time to take an annual deer.

His real dream, however, was that some day he’d be able to take on a Canadian hunt for a big ram; and during the past few years he’d done something about it. A space on his wall was already reserved for a wall-mount of the intended trophy. He’d painstakingly saved a few sheckles so that when the opportunity came, he’d be able to take advantage.

Last fall it came. At the moment, Weldon, the two guides, and I were bellying the rocks of the alpine ridge, just off the glacier, and peering breathlessly over the crest. In the green saddle beyond, eleven Stone Sheep rams grazed, unsuspecting. Most of them were approximately two hundred fifty yards away. In the pale light of early morning, and while moving slowly under the shadow of the eastern peaks, they were but eerie, white-splotched apparitions.

Through the glass, the guide had picked out the two largest—both near the forty-inch class. The closer one was broadside, head down, and with massive horns curling well up above his nose.

“Him big!” the Indian whispered, a grin working up his inscrutable face. His job of guiding was well done, and now completed.

“Take him, Weldon,” I whispered. “Then I’ll try the other one across the gulley.”

That Stone Sheep ram, well into the exceptional-trophy class, was as good as dead. There was no sign of undue excitement on Weldon’s handsome young face, as he wrapped up in the sling. In his hands was his prized .257 Ackley Magnum, doctored up till it would group well into an inch at a hundred yards. Two days before at Dease Lake, Weldon, by way of making sure the 2,000-mile plane ride hadn’t upset the scope, calmly planted two bullets from his wicked hand-loads into a three-inch bull’s-eye at two hundred yards. This, while lying prone over a rolled tent. The ram was but little farther, his noble heart a bigger target.

Other qualities of young Weldon made me certain that he’d never go to pieces when the hunting chips were down. He was a cautious, even-tempered fellow. In his hazardous profession, he didn’t get excited in the presence of danger. His current run of flights was between the West Coast and Hawaii. With but a minimum of checking-out, he had taken our chartered plane over thousands of miles of wilderness bush-country. Several really bad flying conditions had not fazed him—he’d calmly spotted the available holes through “soup,” to where we may have to return and crash-land.

Suddenly, his heavy rifle smashed the ghostly stillness. Ba-loom!

The rams jumped, milled. Weldon shot again. And again, until he had to re-load.

Two days later, Weldon recovered his nerves and settled down to the job at hand. He killed his Stone Ram—the objective of a lifetime. But that first morning, the long dreaming and pent-up excitement was too much. He simply couldn’t hit the longest hair on that ram! I did almost as badly at the ram across the gulley.

This was no rare example of buck-fever. Many a man has waited half a lifetime; gone thousands of miles; and missed his first ram, often under even better conditions. Such is the thrill, the challenge of sheep-hunting….

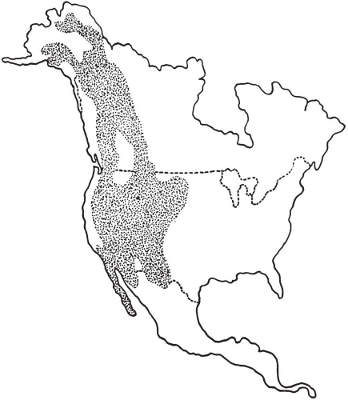

Mountain sheep are found in North America along an extended belt reaching from the northern edge of Old Mexico and Lower California, up through Canada, and into the northern portions of Alaska. Most Canadian sheep are confined to British Columbia, Alberta, and Yukon Territory. In our own country, the overall population is spread upon a range including the western one-third of the United States—less a belt running the length of the Pacific Coast-line, which has no sheep. The United States has an estimated sheep population of around 24,000 head, including the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep and the Desert Bighorns. Alaska has an estimated 30,000 wild sheep.

In a broad way, the Continent’s wild sheep may be divided into three main species: Rocky Mountain Sheep, Ovis canadensis; Stone Sheep, Ovis dalli stonei; and Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli.

The Bighorn Sheep, under this broad classification, includes the Rocky Mountain Bighorn, the Desert Bighorn, and several subspecies of Bighorn Sheep. The Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep is the largest of all North American sheep, and the Desert Bighorn considerably smaller. Big Rocky Mountain rams may reach well over 300 pounds.

The Dall Sheep and the Stone Sheep are classified together as “thin-horned” sheep, as against the more massive horns on the Bighorn. The Dall Sheep is our smallest sheep.

Between the true Dall Sheep and the Stone Sheep, both as to identification and range, is a minor species called the Fannin Sheep, Ovis fannini.

Beginning farthest northward, the Dall is a pure white sheep. This species inhabits Alaska and southward into Yukon Territory. It is commonly accepted that the Dall Sheep’s southern-most range is the south border of Yukon. I have been told, however, by men in the Search & Rescue Division of the military during World War II, that upon being stranded in the bush in northern British Columbia they had observed pure white sheep. These were fellows who had previously been acquainted with Rocky Mountain Goats, and therefore could distinguish between the species. Further, since they were greatly concerned about being rescued from the wilderness, and had more or less to live off the land, their observations about all game has added weight.

At the southern edges of the Dall Sheep’s range, the Fannin Sheep begins. These sheep have nearly white heads, with darker markings on the backs—these colors washing out along the inner legs into a pale gray or white. Big-game biologists do not agree on just where the identification of a Dall Sheep ends and the Fannin identity begins. It is generally assumed that the Dall Sheep and the Stone Sheep interbreed, creating a Fannin type. The Fannin is nick-named “Saddle-Back Sheep.” At a distance, and especially when in motion, this sheep looks as though it wore a saddle-blanket, this giving rise to the name.

From the Yukon Territory southward, throughout British Columbia and Alberta to their southern portions, is found the Stone Sheep. The Stone Sheep’s range is generally north of the Peace River country.

The Bighorn Sheep species begins in southern Alberta and southern British Columbia, and continues southward throughout the Rocky Mountains. At the borders of the Southwest, the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep gives way to the sub-species, Desert Bighorn. Such states as Nevada, Arizona, and southern California contain this species, with the same species spilling over into northern Mexico.

States having the greatest number of sheep within the United States are Colorado and Wyoming, each with an almost identical number and over 5,000 head. Nevada, Arizona, and Idaho are next, with sheep populations in that order.

As with other species, the best place to hunt is generally, in areas of greatest game populations. However, with sheep, which inhabit the most remote and highest areas, the accessibility of any country must be considered. Too, if the hunter seeks the exceptional trophy, he naturally chooses areas where such specimens are located.

With the Bighorn Sheep, those inhabiting the Canadian Rockies are the largest sheep.

Some of the best Stone Sheep country is found at the headwaters of the Muskwa and Prophet Rivers in British Columbia. Another good area is the Cassiar district both near the Stikine River and eastward from Dease Lake into the Blue Sheep Lake area.

Wild sheep live to between ten and fifteen years of age, and generally speaking, the largest heads will be found on the oldest rams. For this reason, the prized heads are ordinarily taken in sheep country which is relatively un-hunted, or at least not over-hunted.

My own Stone Ram taken in 1954 is a fair indication of this. We hunted the Blue Sheep Lake district of British Columbia—this lake being, of course, named after the species of sheep. It was remote country, inaccessible to hunters except by air. We were flown from the outfitter’s main head-quarters at Dease Lake, via Watson Lake in the Yukon. Even at Blue Sheep Lake we were not at the range we wished to hunt. This lake, however, was at the 4,000-foot elevation level, and the last water on which we could set down with the pontoon-equipped ship. From there, we backpacked a spike-camp for five miles up into the base of sheep country, at the 7,000-foot level. This level, incidentally, appears relatively low as compared to the 11,000-foot elevations at which Bighorn Sheep are usually hunted in Wyoming, for instance. But in the Cassiars, 7,000 feet of elevation is high indeed in relation to the low bush country surrounding, and which drains into the Arctic shortly north of there. The actual peaks’ country, too, where the rams were, was considerably higher still.

Because of the remoteness of the region, no white hunter had ever hunted the range we were in. This fact was further made possible through the policy of the province which gives each outfitter a certain specified district in which no other outfitter operates. The ram range opposite Blue Sheep Lake to the west, had been hunted only once before by white men. The native Casca Indians, being hunters, had, of course hunted the entire region. But with these men, hunting was for food, not trophies. A “big” sheep to them meant one having lots of meat, not one with the most headgear. Horns didn’t make soup.

The ram I succeeded in taking was eleven years old, as indicated by his annual growth-rings. He was one of the two largest rams any of our party saw, his full curls measuring just short of 39 inches.

Dal Dalziel, our outfitter, had flown this ram-range several times during the summer, partly to locate the sheep in advance of our arrival. At the beginning of the hunt, he advised me, “Don’t shoot the first ram you see, old man. And don’t take anything short of forty inches. There are rams there which will top the records. I have seen two or three this past summer whose curls would, I am convinced, reach forty-five inches or better.”

I have no reason to doubt him. This man has lived with game all his life, has a critical eye, and is calm in any appraisal. However, when he saw my trophy, he could not help beaming a bit. After all, forty inches of curl is hard to estimate on a ram at three hundred yards. It was till then the biggest ram taken out of the Cassiars that year, and both of us were happy. But Dal was still not satisfied. “Come back another year,” he grinned. “We’ll still take that forty-five-incher.”

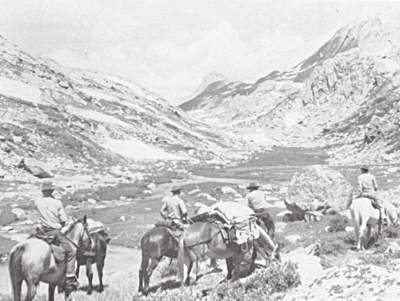

Outfitting for a sheep-hunt involves arranging for the best available transportation to the base of the sheep ranges. After that, sheep are hunted either on horse-back, or on foot. Since the remoteness of a district has a vital bearing on the size of the rams, it’s never smart to get the spike-camp for actual hunting too close to the game.

In the Southwest, the game ranges may be reached via jeep and/or horses. In the Northwest, the standard way of hunting sheep is by saddle-horse and on foot. Horses are either ridden to the base of the crags, tied, and the stalking done on foot, or are ridden up the long barren spines of ridges into actual sheep country.

An exception is the sheep-hunting done in Idaho’s River Of No Return section. The only route through a vast area of this wilderness is by water, down the main river. Once into the stream, the hunter goes on through or else—this giving rise to the river’s famed name.

Many bluff areas bounding the river are some of the best sheep regions. Rams are often seen right from the outfitter’s boat, as they stand on the sides of the near-vertical bluffs and cliffs rising from the river gorge. I have often photographed bands of these sheep, both from a boat and on foot up the bluffs. I find from my notes of 1947 that, while on a fall hunt in this area with Hal Roach, the movie and TV producer, our party counted a total of over 300 sheep right from the boat, on a ten-day’s hunt—incidentally after deer and elk, and not sheep. Most of these animals, too, were ewes and lambs.

Saddle-horses, so useful in ram-hunting, are used in Canada, too, when available. I killed my first Stone Ram in 1947, shortly after the Salmon River trip, while hunting horse-back in the Prochniak Creek area, below Muncho Lake. Pete Petersen, mentioned previously, was outfitting me, and at that time had the last string of horses northward in that entire region. Nothing beats a good saddle-horse for cutting distances in most any kind of game country.

The airplane, equipped with pontoons, has opened up vast areas of the most remote country to the sheep-hunter. The Far North is lake country, with many bodies of water just under the high sheep ranges. Such a lake of a half-mile in length will allow ships to set down and get off with reasonable loads, depending upon altitude. Hunters are flown in, set down, and supplied by air. The actual hunting is then done on foot, with emergency equipment carried on the same pack-board used later, with luck, to tote the cape-and-horns of the ram back.

Sheep-hunting in many Canadian ranges is something like climbing the famed Tetons—one has to siwash out for one night in order to get from where he is to where he’s going.

Some outfitters, and many native Canadians, have solved the problem of taking along enough equipment for such hunting, in a most unique way. They simply break their big sled-dogs to pack, quite like pack-horses. These dogs are enormous as compared to our own domestic pets. Sled-dogs, later needed as purely work animals on the winter trap-lines, will weigh anywhere from sixty to well over a hundred pounds. At age three, such a dog is large and mature enough to pack, and he’ll carry an unbelievable load.

Dal Dalziel, who was breaking such a dog at the time, once told me, “A good big dog will carry from forty to sixty pounds, old man. Not only carry it, but he will get into places no horse could negotiate, and even places where a man can’t go. He will walk logs and along ledges carrying such a load. Further, a hunting-dog is quieter than a horse and always right with you whenever you stop or need him. What’s more, a dog loves such work.”

I had witnessed this fact several years previous. Old Pete Petersen also packed his dogs when he hunted alone, and swore dogs loved packing as much as mushing with a sled. To prove the point, Pete untied his lead dog Tup, incidentally a 120-pounder, and picked up the dog-saddle from the shed.

The moment the beast saw the pack, he wagged his great tail and came up against Pete’s leg, much as a cat sidles against one’s leg expecting to be petted. There, Tup waited without movement for his saddle. It was plain that he loved working for Pete.

A pack-saddle for a dog is made of an opposing pair of canvas bags, quite like small panniers. They are slung low along the dog’s side to keep the center of gravity well down. These bags are connected by a continuous canvas running over the beast’s back. The rigging consists principally of two belly-bands, tied just snug under the dog’s belly. Another such strap of canvas goes around his throat at the brisket, much like the breast-strap of a saw-buck saddle on a mule. Or, the front may be attached to the leather work-collar.

With such transportation, the sheep-hunter who knows his country can unobtrusively work into the game ranges, siwash with adequate equipment and food, and lug the trophy and choice cuts of meat back down. And with a minimum of effort, except for climbing.

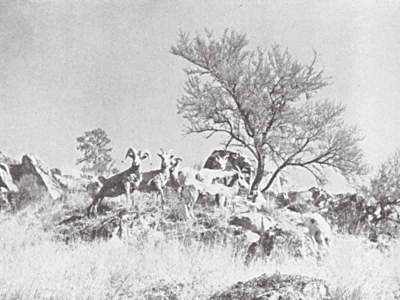

Since sheep-hunting is trophy-hunting, perfection and size are the important considerations in the trophy-head. As with other species, symmetry is most important. Massiveness of horn at the base is also a vital consideration.

Greatest horn-spread, or tip-to-tip measurement is important, too. This dimension varies, as among the different species of sheep. With Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep, the horns are closely set against the face. The horns with this species, further, are habitually more massive in diameter at any segment of the curl than with the Dall or Stone Sheep. Since the horns of the thin-horned sheep are spaced farther from the head, and with outstanding heads, curl to sharper points, the measurements of greatest-spread and longest curls are vital aspects of the Stone and the Dall Sheep trophies.

As examples, record Bighorn Sheep reach 45 inches or more in curl, with tip-to-tip spreads often under two feet. Record Stone Sheep occasionally exceed thirty inches in spread, and at least one ranking head exceeds fifty inches in length-of-curl.