The following information on hunting by moose calls and elevation comes from Chapter 5 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

One method of hunting moose, as practiced by Indian and native guides in Canada, is by means of an artificial moose call. Unless done by an expert, such calling-up, as with other species, becomes largely an aid to conservation. When correctly and judiciously done, the results are sometimes spectacular.

Here is a recent incident illustrating the blind rage of a bull moose, crazed by the heat of the rut:

In the fall of 1955, I hunted elk in Wyoming’s Thorofare area with young Governor Joe Foss of South Dakota. Joe is a strapping six-footer, and anyone familiar with his World War II record knows that he isn’t afraid of man or devil. Governor Joe, incidentally, was the first flying ace of this fracas, and ended up the war with twenty-six downed enemy planes, to tie Eddie Rickenbacker’s record of the first World War.

The day after we bagged our elk, Joe and I went with the packers to haul in the trophies and meat. On the way back to camp, Governor Joe decided to go by way of Bridger Lake with one of the guides and do a bit of fishing. So I went back to camp with the other packer and the mule-string.

When Joe and Dale, the guide, reached the Forest Service cabin at Hawk’s Rest (old land-mark for early explorers into the West, and today just a wilderness out-post), a big cow moose was out in the meadow just beyond, and gawking at them. Joe loves every aspect of the outdoors. In addition to being an avid hunter and fisherman, he’s a camera-nut as well. Here was an opportunity for some fine close-up moose movies. The cow, as are most of the moose in that primitive area, was not at all scared.

So Governor Joe handed Dale his horse, and proceeded to photograph the cow. As he ground the camera, Joe kept slowly moving towards the beast, till she almost filled his finder.

With all the footage he wanted, Joe then proceeded to experiment, largely for the hell of it. Cupping his big hands to his mouth, he let out a moose call. “U-u-u-waugh! U-u-u-waugh!“

The effect startled even Joe. Before he could interpret the intentions of the cow, a great bull with head like the Charter Oak, came bursting from the surrounding willows and jack-pines. Evidently, Joe’s home-made moose call was more authentic than even the cow’s love-call. With a crazed eye toward immediate mating, the big bull came at him in a high trot, paying no attention whatever to the amazed cow moose. The beast never stopped or slowed down.

Governor Joe is never one to disregard a sudden opportunity. Turning the movie-camera on the bull, Joe ground away until the boundaries of his view-finder ran over with bull moose. Then, deciding promptly, agreeing with Shakespeare, that discretion was the better part of valor, Joe high-tailed it for the cabin. He just made it to the porch and vaulted upon it—likely the one time in his forty years that Governor Joe Foss ever ran from anything.

In telling about the affair that night, Joe grinned, a bit red-faced. “I sure want to see how those pictures turn out!”

This instance does indicate the effectiveness of “calling” bull moose, if done flawlessly, and whether intentional or not.

Moose calling, as practiced in Canada, is the reverse of bugling for bull elk, in that the natural call of the cow moose is duplicated, not the wild call of the bull. As with any species of game or birds, successful moose calling is based upon a thorough, intimate knowledge of the game; the meaning which the natural calling is meant to depict; and upon a complete familiarity with the wild call of the quarry itself. It is, naturally, impossible to duplicate the sounds or intention of a game animal without such a basic understanding, coupled to extensive practice with an artificial call.

In moose calling, the brassy call of a cow moose, well seasoned with passion, is duplicated. Indians and white natives who practice the art either call through the cupped hands, or upon a horn made of dry birch-bark. Moose calling is done from a canoe along lake shores, or from concealment on promontories bordering lakes, peninsulas, or similar areas of land between bodies of water. The separate calls are judiciously spaced, no more than two or three calls being made from one spot, and these spaced at fifteen-minute to half-hour intervals.

An added “attraction” to the moose call is the pouring of water from a hat or the cupped hands into the lake, from a man’s height. This simulates the urinating of the cow, and exaggerates in the bull that get-closer urge.

As with bugling for elk, moose calling is a waste of time during wind. On a clear, calm morning or evening, the sounds of artificial calling on a horn, or falling water—both sounds amplified by the acoustics of flat lake-water—can be heard for a mile or more.

Often bull moose which have been so deceived will charge directly towards the sound. The bush-noise made as the animal approaches is interpreted by the hunter. The course of the bull is marked and the hunter makes ready for the kill. In heavy timber such a beast may not be seen until at close range to the hunter; and, coupled to the fact of the bull’s natural pugnacity during the rut, can provide plenty of excitement.

As with other species, bull moose are not entirely deceived every time, even though rut-crazed. Some innate wariness and curiosity remain, and often as not, the animal will circle back through surrounding timber, to come upon the sounds from the opposing direction. This is to take advantage of the animal’s best-developed special senses. While moose are comparatively stupid, they do have keen senses of smell and hearing, necessary to their survival among predators.

I had this characteristic graphically demonstrated last autumn, while photographing moose in an open meadow. I succeeded in approaching the beasts from fringing jack-pines at sun-up one morning, at slowly-diminishing distances to thirty yards. At this distance, the beasts gawped at me in uncertainty, great ears extended and hackles on the biggest bull of the three gradually rising to upright. I shot and shot till the camera was dry.

At the last click of the shutter, the three animals spooked. They romped away for a hundred yards, angling towards the timber, and were lost to view. From shutter-bug’s habit, I sat down to re-load the camera. Sometime during the process, I heard a faint tick of noise immediately behind me. For such great beasts, moose can move with a minimum of sound when they wish. There, fifteen yards in the trees behind me stood the biggest bull! His hackles already had begun to point my way. Like Governor Joe, I’d lost nothing important in that place, and was entirely thankful that the terrain thereabouts permitted me a rapid sprint laterally along the ground, instead of up a tree.

The more basic method of hunting moose is simply to get into good moose country; continuously glass the “edge” country where timber and meadows join water; locate the quarry; size it up as a trophy, and make the stalk.

For the non-resident hunter this procedure is often simplified by the fact that the law requires a guide. Such a guide, if reputable, knows his country and his game. In advance of the hunt, he has likely marked down the areas of greatest spoor, and the biggest heads. From then on, with trophy moose hunting, the procedure usually becomes not one of finding a moose, but one of finding the moose.

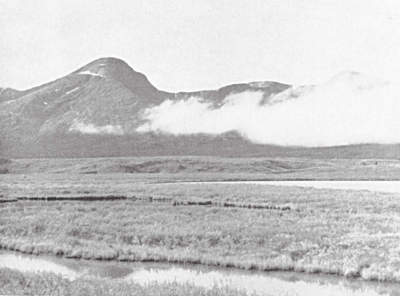

Moose during the normal hunting season of September-October will be found at two elevations. At the daylight and dusk periods, the great animals will be found in the more open meadows, shorelines, and feeding in water. During the warmer hours of mid-day, they move to the slightly-higher elevations of surrounding promontories, benches, low plateaus, willow patches, and low rolling timbered county. An occasional bull will go higher in his wanderings to avoid pest flies or while looking for a mate. But the generality holds true.

Further, moose are non-migratory in the fashion that caribou and elk will shift from a summer to winter range, often at great distances removed. It’s true that deep snows and severe weather will move moose downward to the protection of stream channels, aspen patches, warmer open water, and easier footing, but not away from their normal habitat.

For this reason, a desirable trophy spotted in a certain locale one time may be expected to be there at another period. If a big prized bull has been, or is seen, around a certain lake, he can be expected to be somewhere in the area a month from then.

If the hunter is hunting an area where horses are available, and if he likes to make full use of all the daylight hours because of limited time, then hunting the timber-fringe adjacent to lake and streams is often productive. Moose that habitually “work” any such lakes are apt to be within a belt of timber not exceeding a half-mile beyond water’s edge. They will stand, or lie down in the heavy shade of thick timber. Often the rider will come suddenly upon them at the mild ridge-tops, or just inside the apexes of open meadow “necks” which poke into surrounding timber. Occasionally, too, moose will lie down in the heavy willows collaring bodies of water during the mid-day.

On a Wyoming moose hunt in 1955, we found two big Shiras bulls just inside the timber off a heavily-willowed meadow. Both were in the forty-inch class and decent trophies for the small species, but we held off for a larger beast.

In hunting moose from horse-back during this period of the day, any shooting is apt to be fast. You ride upon another ridge, or around another point. There stands your bull, gawping for a moment at the noise of your horse, then, with bell swinging like a rope, he’s off at an ungainly, swinging trot, looking, as a guide once told me, “like a big black mule crossed with a county backhouse.”

There are advantages to the mid-day hunting of moose. It’s more pleasant to hunt during these hours. One’s vision is better and he gets a better chance to size up the prize. And once the beast is down, conditions are better to take pictures; and there are many remaining daylight hours to dress and care for the carcass and trophy.

Personally, I like the daylight-dusk periods. Most of the animals of an area will appear more in the open at these periods. The hunter’s chances for the biggest one are greater. And, with waning light, the prize is more easily stalked.

The best way of hunting moose during the daylight-dark periods requires time and patience. The hunter should in some way conceal himself at a vantage point where he can command a view of the entire country. Often this is a promontory-point just inside the fringing timber. Sometimes such a point can be found a-top a neighboring bluff, ridge, or lake peninsula.

From there he glasses any animals of the area. Binoculars are a must for this, and the power of the glasses for this type of work should be greater than for elk-hunting and similar scrutiny. With a sitting position, elbows on the knees, and hands steadying the instrument, as much as ten-power or more can be utilized.

One of the best instruments for this type of work is a good spotting telescope. In 1954 my Canadian guide used an old-fashioned nautical telescope for such purposes. While hunting, the glass was telescoped together and carried in the pack-sack. In use, it was extended and laid upon the up-raised pack-board. From a sitting position, and with the front end of the glass on the pack-board “bipod,” the guide could hold the piece entirely steady. Country for literally miles could be spotted, and game located and appraised. This glass was forty-power.

An even better scope for this work I’ve found is a modern spotting-scope and stand, as used for bench-rest rifle-shooting. The one I use is a Bushnell, having eye-pieces of either 25- or 40-power, and mounted upon a Freeland tripod. This outfit folds for easy carrying either in the pack-sack or in the saddle-bags of a stock saddle. With it the hunter can save miles of leg-work, often being able to spot his game from camp.

What represents a good, or an exceptional moose trophy? And, how may one accurately judge the dimensions of such a live beast in advance, and under the stress of hunter-excitement?

The record heads for this species have previously been noted, as to antler-spread. Certainly not every hunter is going to bag a record head, or come near it. There are, however, many bull moose of the exceptional-trophy class still roaming the woods. There are likely many heads which will tie the records, some that may break them. With a knowledge of the record measurements, and a clear mental picture of such a size in mind, the hunter is in a far better position to ascertain the potential of his own quarry.

In sizing up a moose trophy, antler-spread is only one basic consideration. Trophy moose heads are scored on at least a half-dozen measurements and norms: spread, symmetry, number of points, width and length of palms, beam circumference, abnormalities, and differences in measurements and points as between right and left antlers.

One of the most important considerations in a moose head is symmetry. A head with ten points to each antler is a better head as to points than one with thirteen points on one antler, and eight on the other.

Size and symmetry of the palms, or “shovels” is another vital consideration in a moose trophy. Palmation is a distinguishing characteristic of moose, and generally speaking, palm-size has a direct ratio to desirability. Record palms for the Alaska species reach over four feet in length and up to twenty inches in width. For the Canadian species, record palms measure up to forty-four inches in length and as much as nineteen inches in width. And for the smallest, Shiras moose, there are recorded palm-measurements of forty inches in length and up to fourteen inches in width.

What is four feet, six feet, or forty inches?

To the man at his desk, around home, or with smaller surroundings, any such dimensions form a firm mental picture. The average fellow can estimate such measurements with fair accuracy. But under the stress of big-game hunting, the situation is far different. The hunter has long built up a conditioning of eagerness, excitement, anticipation, desire, and mental picture of his trophies for the Great Day when he can at least go hunting. These are often out of proportion to actuality. These keenest of feelings are vastly augmented at the sudden or surprising appearance of really big big-game. The hunter sees things, not as they are, but often as he’d like them.

I have, for example, witnessed hunters swear they shot the biggest buck antelope or deer in existence—only to have them romp up to their deceased prizes and discover they’d busted does, fawns or yearlings. Game for such eager fellows, understandably enlarges in proportion to their desires, and even while they look at it.

Conversely, there is an occasional fellow of phlegmatic temperament, such as my neighbor Jimmy, who sees his prize oppositely. Jimmy, at fourteen years of age, wanted a real big deer for his first—largely to christen his new rifle properly. Upon seeing his first mule buck, he debated at some length with himself as to whether the viewed buck was big enough for the purpose. At length convincing himself that a buck in the skillet beat one on the hoof, Jimmy calmly busted the animal. Its antler-spread was thirty-nine and one-half inches. The head boasted over twenty normal points—and set a local record!

The best ways I’ve ever found for pre-determining the antler-size of any game species in the hunting field, is to estimate the antlers, or horns, in terms of animal-size. This estimation, in turn, should be narrowed down to the known measurement of some feature of the beast—overall length, height, width, or dimension of some outstanding feature.

With moose, the antlers may be studied in comparison to the following: height at withers, depth of body (withers to belly-line), length of body, and overall animal-length.

Specifically, an adult Alaska moose will stand between seven and seven and one-half feet tall at the withers. His body will be approximately four feet in vertical depth. His belly-line will be off the ground a bit over three feet. Body-length from point of the shoulder to tail will be just over six feet.

Similar measurements on the smallest species, the Shiras, will be, for adult bulls, approximately five and one-half feet in height at the withers, close to three feet in body-depth, belly-line thirty inches off the ground, and overall body-length four and one-half feet.

Canadian moose average approximately mid-way between Alaska and Shiras moose in these measurements.

A conception of these dimensions should be visualized and taken to the hunting-field by the hunter. Such feature-measurements cannot of course, be entirely accurate. They will vary with the species and the individual animal. Further, in conditions surrounding the appearance of game, any accurate estimation is uncertain. The game may be running, quartering away so that a feature is partially obscured, or is hidden by foliage, water, or terrain.

These facts do not spoil the value of such an estimation, but rather, make it even more valuable during attendant hunter-excitement and the tendency to see one’s trophy as he wants it, not as it actually is. For example, the hunter who studies his Shiras moose in the glass and notices that, as the beast turns end-wise, his antler-spread is only a bit over one-half the animal’s height at the withers, that hunter knows for sure that the antlers won’t be over three feet in width. This, no matter how excited he is.

Again, if the width of the palms as the beast feeds broadside appear to be at least one-third of the distance from hoofs to belly-line, then the hunter equipped with this pre-knowledge knows they’re mighty good.

From similar comparison of the head with other known dimensions, he can pretty well size it up as to desirability. The number of points can usually be counted with a good scope from an approachable distance. Their number, in relation to size, may be integrated with other estimations.

Young bulls can ordinarily be easily sorted from big trophy bulls in this way, even by average, inexperienced hunters. The guide, too, fulfills one of his most important duties, and obligations also, in the matter of similarly carefully appraising a trophy’s potential, before the decision to stalk and shoot.

However, as with grizzlies and other big species, two men’s considered opinions are better than one’s, assuming that both are on an intelligent basis. Occasionally, a guide with little time further to spend, or who has for other reasons failed to have his hunter connect, mentally “enlarges” what turns out to be a mediocre trophy.

There is another rough rule-of-thumb for sizing up a moose head, which is especially helpful in instances where the hunter flushes his quarry, and must size it up in a hurry. I have found that when adult bull moose turn head-one, or head-away, and the hunter’s honest impression is that the animal is in “thirds,” it’s a mighty good trophy. By thirds I mean that there appears to be as much distance between body and antler-tip on one side, as there is body between, as there is space between body-and-antler on the opposing side.

Further, if the bull is mature and, as he moves, gives the impression that his antler-width approaches his height, he’s in the exceptional-trophy class, or better.

We used a combination of these methods of field estimation in order to determine, in advance of shooting, the trophy-potential of my Shiras bull moose in 1955. The bull, during those breathtaking seconds prior to the stalk and crack of the rifle, fulfilled all the above estimates. This bull, upon subsequent measurements, proved to be most exceptional, and is currently entered in the Boone and Crockett Club’s competition. From the information of current listings, this bull apparently is going to rank in the world records. His measurements are:

Greatest spread, 51 inches. Points, 10 right, 12 left. Width of Palms, 13 6/8 right, 13 left. Length of palms, 32 1/8 right, 33 3/8 left. Circumference of beam at smallest diameter 7 6/8 right, 7 5/8 left. No abnormal points.

Moose are relatively pugnacious. Cows with calves are nice animals to let alone, as many an enthusiastic photographer who wants a shot of the young, ungainly brutes can testify. Cows without calves, too, occasionally take fishermen up trees; and once they succeed in bluffing a human, they take a cantankerous delight in repeating the process. I once had to take to the tall timber in a hurry, while photographing a cow moose in eastern Idaho at close range. I was on webs at the time, and discovered after the photos were taken that the cow too could run on the snow crust! I was “moved” with some degree of suddenness, too, a couple of times in Wyoming’s Buffalo River area, while photographing moose in the spring. The mistake here was the assumption on my part that bull moose with antlers just beginning—mere clubs of velvet—would not charge. The fact was, the ticks were aggravating the animals at this season, putting them in no mood to be pushed around.

Bull moose during the heat of the rut often become most pugnacious, and often a real nuisance around a wilderness hunting or fishing camp. This is especially true in areas where the big beasts are relatively unhunted.

Sandy Sanders and I have both been taken promptly off the latrine of his hunting camp on Atlantic Creek, and full into the tents by the same bull moose on the prod. In each case the animal came plowing through the adjoining timber, chomping his teeth, grunting, and with hackle up, right at us. It’s startling, to say the least, to finish up the morning chores under such unexpected conditions.

Again, a year ago this past fall, the cook at our hunting-camp was thoroughly charged by a great bull moose, while riding across the meadow on a saddle-horse. The cook had to circle, ford a sizeable stream twice, and come full into the camp clearing on a dead run with the horse, just ahead of the rut-crazed beast.

Or, a couple of years ago at Two Ocean Pass, I had three moose, two cows and a young bull, follow my saddle-horse on a trot for a half-mile, after spotting us in the meadow. When the bull had cut the intervening distance to two hundred yards, I veered the horse towards him, hoping to get a picture. This nerve-tingling approach went on until the bull reached the creek on one side, with me and the horse on the other. The horse, used to the moose of this area, stood his ground. The bull across the creek was angry enough to paw the muck, roll in it, shake his polished antlers, and otherwise act similar to a maddened domestic bull. I might add that I already had some handy timber spotted, and half-expected a sudden spurt of “horse opera” at any moment. As often is the case with moose, however, this bull, upon finding his bluff called, didn’t finish what he originally started to do. I left him grunting, pawing, and chomping.

Moose on the prod are not dangerous game in the sense that grizzly bear are dangerous. I have a couple of friends who have roosted up pine trees, up to two hours at a time (after coming across a moose while fishing), who very much doubt this statement.

The element of danger does, however, have a bearing on the rifle-and-cartridge which the hunter uses for the massive animals.

What is a suitable rifle for moose?

Moose are deer. As deer, they are no harder to kill in proportion to their size. Even the big bulls are not tough to dispatch in the same degree as are bull elk. A good rule-of-thumb is this: If the successful deer-hunter will multiply his ordnance-power by from three to four, he’ll have a suitable outfit for moose. In brief, if he can regularly kill mule deer of up to two-hundred-fifty pounds with a .257 Roberts, then a cartridge having four times the ballistic equivalent is ample for a moose weighing a thousand pounds.

In the case of moose, however, there is a modifying influence. Moose are big, relatively slow of movement, and not quick-witted in the sense that sheep, grizzlies, and other species are uncanny. Moose are often spotted, then stalked to close range for the shot. Even after being spooked and while in flight, they represent big targets, moving in a somewhat steady lateral plane—not bouncing up and down like whitetails.

Such a combination of factors makes it possible for the hunter to shoot with far more certainty into a vital area than, say, shooting at grizzlies bounding along in the bush. As the certainty of hitting a vital area of the quarry increases, the need for extra power in the rifle decreases.

The Indian in the Far North regularly kills his moose with the old .30-30 common to that region. Such a man is a hunter by occupation, lives in an abundant game population, shoots many animals for food and for dog-food, and has the time and patience both to wait for a good shot and to wait for his game to die after being hit. Further, his moose is habitually a cow moose. “Horns” to the Indian and native hunter, can’t be eaten, therefore there’s little reason for killing bulls. Cows are proportionately easier to kill than bulls.

Sportsmen-hunters both in the States and in Canada regularly use rifles from about the power of the .300 Savage on up, on moose. Usually they don’t complain about lack of power, if they get a decent shot at fairly close range. Some examples may be indicative:

Major C. B. Harris, a hunting partner of mine from Virginia, has had wide experience on Canadian moose. He habitually used a standard 8mm. with heavy factory loads on “Uncle Sam’s mules” as he calls them. This spring, in a telephone conversation, he told me, “I kinda liked the looks of your Weatherby .300 Magnum. There was one on display at the Sportmen’s Show here a while back. So now I’m a Magnum man.”

My first Idaho moose was killed with a 180-grain Silvertip bullet shot from a standard .300 H&H Magnum, Model 70 Winchester. It was a running shot, through the lungs, at a bit over one hundred yards as the bull made off through scrub aspens. The beast gave no indication of being hit. After running forty yards, it piled up and was dead when Walt (my guide) and I reached it.

The big Wyoming moose previously mentioned, which I killed in 1955, was shot under what were most exciting and difficult circumstances. I shot the bull three times with a .300 Weatherby Magnum, using Hornady 220-grain soft-point bullets ahead of 70 grains of #4350 powder. This load, incidentally, was most accurate and was loaded especially for that particular hunt. It was quite authoritative, and, while being tested on the bench-rest, would set the shooter back about a “hat and one-half.”

The difficulty surrounding this particular shot lay in the fact that the great bull stood precisely behind another bull—itself in the trophy class—and both in belly-deep water. I wanted to kill the bigger bull with certainty, but didn’t want him to drop into the water. The first shot caught him full through the lungs. The second, as he quartered away, severed four ribs of his “slats” and entered the lung-chamber. The third in the spine was just a snap shot. The bull staggered twenty to thirty yards up out of the slough onto the bank, made it to the surrounding willows, and collapsed. No shot other than the first was at all necessary. But, as with other really big species, any hit except somewhere along the spinal-length is not apt to tip over the animal—even a heart shot. Under the stress of hunting excitement there comes a basic doubt in one’s shooting. No game animal still on its feet is dead.

In a broad way, the most suitable rifles and cartridges for moose coincide with the rifles most suited for grizzly-hunting. Rifles of large caliber and great knock-down power, such as the .348 Winchester, the new .358 Winchester, the old .35 Winchester, the .35 Whelen, the .405 Winchester, and wildcat cartridges of comparable ballistics, are all fine for the close-range shooting often common to moose hunting. Where the hunter’s trip is set up for other species of big game as well, such as grizzly, sheep, or caribou, a flatter-shooting rifle needed for these other species had better be chosen. The .300 H&H, .300 Weatherby, .375 H&H, and the various wildcat Magnums of .30-caliber and up, are fine choices.

When the prized animal is down, there are certain necessary chores. First is the matter of pictures. Every hunter of really big big-game should carry some kind of a camera, either movie or still. Pictures of the prized trophy become increasingly priceless as the years go by. They are also invaluable as a guide for the taxidermist in re-creating the mount to its natural proportions.

For this use, photos should be taken which clearly depict the following: greatest spread, or head-on of the animal; side views of the head-and-cape section, both right and left sides of the animal; any unusual or abnormal features which distinguish the trophy from other specimens of the same species, such as abnormal antler-points, unusual bell, etc.

Such pictures, except for close-ups of particular features, should be made at distances of ten feet and beyond for the average cameras having lenses of around four-inch focal length. This is to prevent distortion in animal-proportion caused by fore-shortening and exaggeration—inherent faults of lenses at extremely close range.

In addition to photos, which any hunter can learn to take in an hour or two’s study, even with a new camera, certain field-measurements are needed on the spot. In the preparation of capes and skulls for later mounting, the animal’s true proportions become lost due to hide-shrinkage while drying, and in the process of skin-pickling. When stretching the prepared hide back to normal for the finished mount, and when substituting a paper-mache head-form for the usually discarded skull, the taxidermist needs some sort of guide as to measurements. These cannot be had except from the hunter, who makes the measurements while the trophy is still fresh.

Taxidermists differ in what is required as to measurements, depending upon their own field-knowledge of the species of game. Frank Keefer, my own taxidermist and one of the best in the West, can duplicate the original head as to proportion, with but two field measurements: distance from lower edge of bony eye orbit to tip of the nose, and the distance from medulla down over the face between the antlers to tip of the nose.

It’s better to have too many measurements than too few. If the hunter will make the above measurements with a tape stretched just taut, and add the following, any good taxidermist can then shape the finished mount into the correct proportions:

Smallest neck circumference, at a point just behind the lower jaw.

Circumference of neck mid-way between jaw and shoulder.

Neck-circumference at the point of the shoulder.

Distance across the face of skull, from outside edges of bony eye-sockets on each side.

The basic measurements for moose antlers themselves are: greatest spread; points on each antler; circumference of each antler at the burr; circumference of each antler at smallest diameter; length of each palm, measured along a line parallel to the inner edge of the palm and at the greatest length of palm; and the width of each palm, measured on under side of palm, from inner edge to a dip between points at greatest width.

All measurements should be jotted down in a note book where they won’t be forgotten.

Where distances to the hunting-field are not too great, and the weather is cold, the trophy will keep for three or four days if skinned only from the shoulders to the head—the head being then twisted or cut off and left intact with the cape.

In cases where heat, time, or blowflies would spoil the flesh, causing the hair to subsequently slip, the entire head must be skinned out, fleshed, dried, and salted. The skull itself is not ordinarily used in the finished mount. Only a skull-plate containing the antlers is saved. This portion is bolted to a head-form made of paper-mache, and covered with the prepared skin.

Today’s non-resident, or visiting, hunter usually doesn’t have to field-care for his trophy. This is an integral part of the guide’s job, for which skill the “dude” pays. Many times, however, the hunter is a resident and hunts on his own in a province or state which doesn’t require a guide for residents. Then he must care for his own trophy. Or again, even though the guide does the caping-out of the trophy, the hunter wants to help and needs to know how. Another thing, he can make everlastingly certain that the guide doesn’t cut the cape off too short at the neck-shoulder line—a fault common to too many guides having limited experience.

Moose trophies and similar heads meant for wall-mounts are caped out after making but one basic cut in the skin: Beginning at a point exactly over the withers, a cut is first made down the middle of the front shoulder blades (as the shoulder lays normally in place), and to a point well back of the brisket on either side, and ending at a point mid-way of the sternum. Again beginning at the point of the withers, the cut is extended lengthwise up the back of the neck to a point mid-way between the ears at the top of the head. Here the cut divides, a cut going to each of the antlers.

No other cutting of the skin is necessary. If the skull has to be skinned out completely, it is carefully “peeled” down over the face. Extreme care should be used around the ears, eyes, and lips. Ears should be cut off flush with the skull. The skin from the eyes should be removed without any cutting of the lids—just cutting the thin conjunctiva. The lips should be severed by cutting the skin well inside the mouth.

Two basic mistakes in removing capes will make any taxidermist tear his hair and cuss. One is to cut the cape too short, not leaving enough hide for a good shoulder mount. The other is to cut the hide up the throat. Doing this really makes a taxidermist blow his top, and it should. There is no necessity for such a mistake. The resultant trophy never looks entirely natural, but instead has a permanent “rope” of sewing up the entire length of the neck.

Removed capes should be dried as quickly as possible, and salted. All pockets and folds in the hide should be carefully watched. Heating, prolonged moisture, and blowflies will quickly make the hair around such areas slip, ruining the cape. Clean burlap bags are fine for hauling the thoroughly-dried and well-salted capes to the home taxidermist, or for shipping the trophies.

In cases where the skull must be discarded and only the antlers saved, the “plate” containing these valued features is cut away either with a small saw, or, most carefully, with a good ax. Cut first through the skull bone about three to four inches behind the antlers, and all the way across the skull. Join the ends of this cut with other cuts through the center of the eye-orbit, and continue these two side cuts until they can be made to join mid-way down the face. The brains clinging to the under side of this plate can be scraped away, and the remaining plate dried for transit.

The hunter who will take such simple pains immediately after his prized trophy is down has made it possible for any good taxidermist to finish up the mount in an artistic manner. The trophy-artist can then, as Frank Keefer says in his advertising, “make the dead come alive.”