The following information on hunting the Rocky Mountain goat comes from Chapter 13 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

The Rocky Mountain Goat, Oreamnos montanus, is the smallest big-game animal considered in this volume. It takes a large adult to weigh much in excess of 250 pounds, though an exceptional billy may reach 300. In so far as mere weight is concerned, the mountain goat may well be classified as but “medium” game.

Conditions surrounding the hunting of goats, however, are the most difficult and rugged. Goat-hunting involves the hardest hunting imaginable: the most extremes of elevation, and the most treacherous and dangerous terrain. For these reasons, plus the fact that the mountain goat is comparatively scarce, he may well be classed with the biggest American game.

If any clincher is needed, it is the bald fact that a Rocky Mountain Billy is, pound for pound, the hardest North American game animal to kill. He is phlegmatic in temperament, spongy of flesh, and impervious, in the same sense that thin-skinned game is, to the shock of bullets. A big goat will withstand rifle-fire that would bowl over another beast of comparable or larger size, with no visible indication of being hit.

The most extreme example of this I know occurred to a hunting partner, Dr. “Jake” Jacobs, in the Cassiar Mountains of British Columbia. The occurrence is so unusual as to tax the credulity of the average hunter. It is not set down here as an average reaction, but rather, as an extreme example of what any wild animal can, under certain conditions, withstand.

Dr. Jake discussed the affair at length around the camp the day following. But in order to get all the details, I wrote him, lately, asking to write it in his own words. Here’s his reply:

“My guide, Amos, spotted the goat while we were starting preparations for breakfast.

“I set out after him with the .270. The rifle was sighted in to be dead on at 200 yards.

“Close to noon, we were climbing up some step-like, black granite escarpments just above timberline. I was in the lead and Amos shortly behind me. We knew we were near the goat and were stalking as warily as we could.

“On topping out where we expected to see the animal, and with just my head exposed over the top, I saw the goat. He was not more than a hundred feet away and level with us. Amos was perhaps 20 or 30 feet below me. I drew a bead on the goat’s shoulder and shot with no apparent results. The goat had simply turned his head as I had shot.

“Just about the time I pulled off the second shot at his shoulder, Amos, who had reached me, said, ‘You hit!’ This, just as the fur flew. Thereupon, the goat got up and started slowly to walk up the mountainside, and I finished him off with a third shot, again in the shoulders.

“Because I had promised the entire hide and head to the University of Idaho for their Research Department, and this animal was to be mounted as a full mount, I had Amos skin him down the back. When the hide was pretty well peeled off the back and shoulders, my good guide remarked that I had only hit him twice, both times shoulder shots, either of which should have killed him as I was shooting the standard 150-grain bullet.

“The next day when Amos was skinning out the head, he called me to show me where the first bullet had entered the goat’s right nostril, and had pretty well shattered the lower part of the skull, with no wound of exit present. His position, lying down on the rock, was such that turning his head toward me allowed such a shot. How he ever lived even a moment after a lower brain shot like that, I can’t imagine!”

There is little need to elaborate. A brain shot, on most any big-game, will drop it in its tracks with the beast virtually dead before it hits the earth. This animal not only absorbed the shot, but actually rose and staggered off.

In discussing the affair at the time, I expressed near-unbelief. Jake, being a surgeon, explained that often, with humans, parts of the brain can be removed with the patient living afterward. This, despite Doc’s entire honesty and indubitable proof of what had occurred, is still most amazing.

Other hunters have had less dramatic, but nevertheless downright startling experiences with these mountain beasts. Some have literally shot a billy’s heart to pieces, having him react no more visibly than to stand and gawp—then, thirty seconds later, keel off the cliff into the canyon.

I have shot Rocky Mountain goats with both a 7mm. and a .300 H&H Magnum, squarely through the “boiler-room,” without either causing them to flinch or, if in motion, to break stride. Goats seem to accept with philosophy vital shots which would tip over the biggest mule deer bucks, or make a big bull elk at least go to his knees.

As compared with other species, the Rocky Mountain Goat is few in numbers. There are approximately 16,000 goats. The vast majority of these are in British Columbia. Other lesser goat populations are in Alberta, Yukon Territory, southern Alaska, and the Kenai Peninsula. Natural goat populations are also found in three of our Western states, and an artificial population has been successfully introduced into South Dakota. In the United States, the states of Washington, Montana, and Idaho have a relative abundance of these shaggy white animals, their numbers being in that order.

Old Oreamnos montanus is not a true goat, but more of an antelope resembling the chamois. As with caribou, both sexes are horned. At the extended distances which goats are usually seen, there is no distinguishing characteristic between the billies and the nannies. Size may be an indication, but size is difficult to determine in goat country. Goats spotted against contrasting backgrounds such as barren rocks, slides, and green sidehills may look unduly large. Conversely, goats seen against patches of snow, or the large, light-colored granite boulders of an eroded bluff may appear small in proportion.

Habit is the hunter’s best clue to sex. In the fall season, and before the rut begins, the prized billies are ordinarily found alone. Nannies, on the other hand, usually stay with the kids or other females.

If one were to take a map of the Continent, and sort out that portion having the highest cliffs, he would have a section co-incident with the Rocky Mountain Goat population. This animal is a cliff-dweller by nature, inhabiting the highest, most dizzying peaks, cliffs, and spires. As with other species, his habitat is determined by the food supply and the advantages which terrain gives over enemies.

The goat’s main food supply is moss, and the lichen which grows to the sides of peaks, spires, and shelving ledges. His white shaggy coat affords protection against the eternal cold and wind of his peaks’ home, and camouflage in snow-patches and rocks against the vision of his foes. Bears and wolves cannot successfully follow the goat into his upper reaches, since they do not have comparable “traction.” Eagles kill goat kids, but cannot hurt the mature billies and nannies.

Even in the broad reaches of his habitat, the goat does not migrate. He may change altitudes, due to his need for food, water, or to change sides of the drainage. But it is axiomatic that if a goat, a family, or a population of goats are found on a certain mountain one season or year, they will be there another.

I have seen this time after time in the Salmon River Gorge. On spring expeditions after steelhead, I have for three consecutive years seen what undoubtedly was the same old billy, high up the sheer bluffs just below Salmon Falls. On another bluff area farther down, our party has seen the same family of goats for at least four trips out of seven—with no other goats ever seen for twenty or thirty miles either upstream or down. Don Smith, the boat-outfitter, tells me that over the years that particular group of goats has never moved off that mountain area. Don makes numerous trips each year, and has been running the river for over twenty years.

Hunting Rocky Mountain goats is the hardest physical work imaginable. The “opponent” is a combination of gravity, elevation, and footing—all at their extremes. Only the hunter in good condition should attempt it, and the man much past middle-age had best get his goat-hunting done while there is time.

Since the best chances for success come where the game population is greatest, the goat-hunter’s choice may well be British Columbia if he has the time and means. The goat’s range there includes virtually all the province; but as with the other areas, the very highest crags country is best. The Cassiar-Telegraph Creek-Stikine River region is among the very best. Goats may be hunted there in conjunction with grizzly, sheep, and moose—depending upon elevation—and are found in relative abundance. Too, there is a general open season on the animals there. In addition to the animals’ numbers in that area, the exceptional trophies for the species are also in that general section.

As an example, of the twenty top-ranking goat trophies, a majority came from British Columbia. Half of these heads came from the Cassiar-Telegraph Creek country. In addition to the goats seen while hunting in this area, I have seen numerous animals in the cliffs country while flying from the Stikine River to Dease Lake, and thence eastward to the Granite Lake-Blue Sheep Lake areas.

Goat-hunting in the States is done on a permit basis. Idaho is a good example. For years there wasn’t too much known about the goat population in this state. It was thought by some that the animals were headed for extinction and the remaining numbers should be saved, through the abolition of all hunting, for scenic value.

At this time, Idaho made an intensive study of the Rocky Mountain goat, under the direction of my friend, Stewart Brandbourg. This study covered a three-year period, was most intensive, and was conducted in goat habitat. What Montana had already learned of their own goat population and trends was added to these findings. In fact, many of the techniques which the Montana game biologists had learned, were used in the Idaho study. So Montana deserves much of the credit.

As a result of Brandbourg’s study, the state recommended that the goats be protected to the point where their numbers would reach the carrying capacity of available ranges; and thereafter the increase would be hunter-harvested, allowing a reasonable margin for error and emergency. In order not to decimate any spot-populations, all goat-range was divided into areas. On the basis of the census in each area, a number of permits would be issued for adult animals.

This has worked out most satisfactorily. The season of 1955 represents an indicative picture both of the hunter’s opportunity, and his probable success-ratio. During this season, 43 permits were issued. Of this number, 22 killed goats, with one hunt having 5 permits not yet reported, at this writing.

From this it will be seen that goat-hunting in the States depends upon two things—getting a lucky permit, and doing some subsequent hard hunting.

The technique of hunting Rocky Mountain goats is fairly simple. Basically, the hunter gets into a country of known goat-populations. There he patiently glasses all available terrain above him. If no game is sighted, he then moves on to another position and repeats the process. If animals are still not sighted, but are known to range there, it is safe to assume that they are “around the mountain” somewhere.

During hunting season when the country is bare of snow, goats are easy to spot. They show up as white dots, having great contrast against shelving ledges, blue-gray cliffs, and lichen-covered granite. In areas of glacial boulders, however, the animals are easily mistaken for rocks or snow-patches. Their white, slightly cream-colored hair takes on the reflected light of surrounding objects, and may appear at great distances as tints of yellow, blue, dirty gray, or even green. Added to this is the fact that the contour of animals standing still or lying down naturally blends with the landscape; and also, animals are easily hidden from view by such rocks.

The hunter cannot study the areas of known goat country too carefully. Often he detects game only when it starts to move. Other times, a slight change in vantage-point will give him a view of animals which, from another angle, he could not see.

Once the animals are spotted, the hard work of climbing and stalking begins. Before beginning the hard climb, the hunter should first study the country meticulously, both for the best possible routes to the game, and also for possible routes and directions the game itself might go. Many times, the goat-hunter will make a hard half-day’s climb, only to discover that the game meantime has moved into inaccessibility.

Emery Lent and I once had this demonstrated the hard way. We were not at the time hunting, but rather stalking the white bluff-inhabitants in an attempt to photograph them at close range. The technique, however, was identical to that of hunting with a rifle, except that, with a Speed Graphic, one has to get even closer.

We were at the time beyond road’s-end down the main Salmon River, and had climbed perhaps a mile up out of the main gorge and into a great side basin, hemmed all around with ledges and sheer precipices. We’d been told that a family of goats lived in this remote, virtually inaccessible basin, and we hoped, someway, to locate them and approach to within telephoto-lens range.

As we glassed the area with the binoculars, we suddenly picked up a monstrous billy. He was not up in the cliffs of the basin-side where we’d expected the game, but rather in a small, more available saddle to the right. At a distance, Old Bill moseyed around like a great white grizzly, with the hump at his withers almost identical in appearance. He didn’t appear to be going anywhere in particular. He’d feed for a while, then turn endwise and stand dead still, to gawp off down into the river gorge.

By circling the head of an intervening gulley, so as to keep out of sight under the opposite crest, we hoped to approach him.

That whole country, however, is virtually on end. It is spewed up in one majestic upheaval of creation, seemingly without pattern or reason. Any climbing, or moving about in it, is usually all up or down, and most difficult as to footing.

It took us another hour to reach Old Bill. Places where it was all rock, we’d have to jump from boulder to boulder in the talus. Some spots we had to negotiate on all fours. By the time we reached the tiny alpine saddle where the goat was, he wasn’t. There seemed no way, other than the precarious route we’d come, where the beast could have gone. But he seemed to have evaporated completely.

While resting and talking it over, we again spotted the big billy—this time a full half-mile to the east, and now picking his way gingerly but methodically up the sheer face of an opposite cliff. There must have been some route down the intervening gorge between us and the animal, and up the other side. But we couldn’t find it. Old Bill had, like some fly on a wall, stuck to one side of the cliffs going down, vaulted the talus in the bottoms, and inched his sure-footed way up the opposing side.

A similar and typical instance of the normal movement of un-alerted game occurred on my first goat-hunt in British Columbia. This time, I was after the game with a rifle.

Tom Mould, my guide, spotted four animals high up in the crags one day, while we were really investigating a possible route over some glaciers. From the size, the animals appeared to be big billies. They were moving slowly about, feeding in the early hours of the morning. Upon studying them for ten minutes, Tom decided that one of the animals was big enough to go after. There was a reasonably mild route to him, and the beasts likely would soon bed down for the day, high above the Arctic birch in the crags at the south lip of the basin-rim.

We huffed and puffed and sweated our laborious way up there, this time again to find the beasts entirely gone. From a point near where they’d last been seen, we discovered another rocky gorge just beyond—a chasm of sheer walls with glacial-washed boulders in the bottom. Upon studying the country, Tom suddenly spotted the animals again through the binoculars. They were now stopped in the high rocks, on the opposite rim! How they’d made it across the intervening chasm without going nearly a mile up around the basin-apex, we couldn’t figure. But without doubt, they were our goats. The biggest billy now lay across the top of a flat rock, with his fore foot lazily draped over the edge and down, just like the family pooch snoozing on a door-step.

I wanted that goat badly, though we’d have to circle the entire basin to reach him, if and when I did kill him. As is often the case in goat-hunting, he was beyond rifle-range, and apparently no way of getting closer. The animal was a full quarter-mile. Tom sized up the situation once more, after I assured him I couldn’t hit that beast, even from prone with the heavy-barreled .300 H&H Magnum, at such a distance. After scouting a bit, back out of sight, Tom discovered a tiny jutting ledge, farther down the rim, which ended in a precipice over-looking practically nothing out into the gorge. He figured if we could sneak down there without scaring the beasts, we could cut the range to three hundred yards. From there, I’d have a chance.

At this time, something unexpected but representing one of the numerous quirks of fate common to big-game hunting occurred.

From seemingly nowhere, four Stone Sheep calmly walked out onto the open basin-crest, and turned to gawp at us. They were ewes and lambs, curious and alerted. If we moved to reach a closer shooting range, they’d spook and scare the billies. If we waited, the goats would mosey on. Such are the aggravations of the big-game hunter.

I mention this incident mainly to indicate the many, often unexpected little ways in which a goat-hunt may often go sour—often after a day’s exhausting climbing up into, and among the crags.

Actually, Tom, with his great patience and savvy of big-game, waited out the sheep. When they had satisfied their curiosity, and had moved to where he could get between them and the goats, Tom slowly and casually moseyed over to the jutting precipice. “If I make it without scaring the goats, you come over,” he told me. “Otherwise, if the big billy gets up and starts to move off, you’d better try a shot from where you are.”

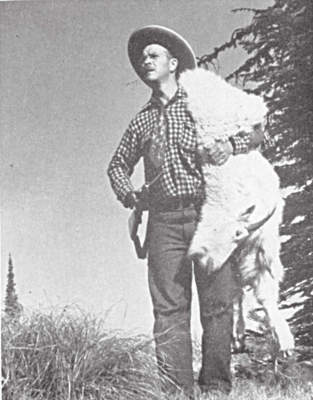

We both made it to the closer range. The big goat still dozed over the flat rock. From prone, and with sling, I missed him completely the first shot, holding a bit too high. At the smash of the report, the beast jumped full upon the rock, turned broadside, and gawped around in our direction. At the second shot, Tom saw a puff or white fur fly from his rib-cage, through the binoculars. That goat-head is now on my shop-wall.

There is another difficulty to goat-hunting, discovered even after the game has been spotted and stalked to where it is known to be. By its very rugged, broken nature, goat-country limits visibility both laterally and vertically. The hunter may, while climbing around in the cliffs, be within fifty feet of the game, yet with neither being able to see the other. Rocks, jutting cliffs, and talus may intervene.

A good stunt for the hunter who is reasonably certain that his game is within range but hidden, in such areas, is to pick his way somehow to where a rock may be rolled into a crevice, V-gulley, or apex of a talus-slide. If he has previously been careful to make his stalk noiseless, and the rolling rock is the only sound, then any goats within the immediate area are almost certain to get to their feet, and stick their heads up above the intervening rocks to see what all the fuss is about—if the hunter remains quiet.

Old-timers in the Salmon country have told me that this way repeatedly produced on goats, where otherwise they’d be skunked after a hard day’s climb. Goats have an innate curiosity.

The actual shooting of, or at, goats, involves a technique a bit different than for certain other species of big-game. Alerted goats don’t break fast from the scene in the way a buck deer bounds off, or a scared bear “scissors” his feet rapidly beneath him. There usually is time for precision shooting. However, the actual target-area on a moving goat is deceptive. His long shaggy hair undulates both up and down, and lengthwise—something like a small person running in too-large, woolen underwear. The most certain area at which to shoot is, of course, the shoulder area—that section from spine to belly-line vertically, and brisket to end of rib-cage horizontally. The thing to keep firmly in mind is the location of this vital area in relation to where the hair is flopping at the time.

Our remaining goats should be taken only for trophies. A young goat, I have been told, is palatable. After having skinned out the trophy beasts I’ve personally taken, however, and having to inhale the innate stink of the animals, I’ll stick to elk-steaks.

Since the chin whiskers and the jet, slightly-curving horns of the Rocky Mountain goat are the two most prized features, there is no point in the hunter’s endangering either. The whiskers may handily be saved by proper skinning out and care that the hair doesn’t slip. The black horns, however, are fragile as compared with the headgear of an elk or sheep. Many a fine goat trophy is ruined after the hunter spends thousands of dollars on his hunt, and kills his prized billy.

Why?

The animals love and inhabit the most precipitous places and heights. They are, more often than not, shot as they perch upon some vertical spire, or shelf over-looking a gorge. Added to this is the fact of Billy’s hardness-to-kill. The beast is shot, doesn’t fall and die on the spot, but moves a bit, to topple into the gorge or crevice. The thin brittle horns are usually broken, and the trophy is ruined.

The thinking hunter can usually prevent this. After making the stalk to within range, he should invariably ask these two questions of himself: “Can I kill that goat where he is?” And, “Can I surely get to him, if I do kill him?”

This brings up the matter of suitable rifles. Because of a goat’s toughness to stop, and the uncertain ranges at which he must be shot, I’d place the goat-rifle-and-cartridge in the same class as those needed for elk. As indicated earlier, the sensible goat-rifle is that rifle which will be used on the biggest species of big-game which is to be hunted while on the goat-hunt.

Specifically, if the hunt is for a combination of game from grizzly and moose to goat, then the grizzly rifle becomes an adequate rifle for goats. Rifles of the .300 H&H Magnum class, shooting 180-grain bullets, are ideal. Custom rifles-and-cartridges of the flat-shooting, high-intensity character of the .270 and .300 Weatherby Magnums, are among the very best. Either the 130- or 150-grain bullet in the .270 Magnum and either the 150- or the 180-grain bullet in the .300 would be entirely suitable.

Rifles of larger caliber but slower velocities suitable for the timber or bush-hunting of the largest species—such as the .348 Winchester, .358 Winchester, or .35 Whelen—make good goat-rifles for such areas as the Salmon River gorge, if the shooting is to be done at reasonable ranges.

If I were to list the most important piece of equipment necessary for the successful hunting of Rocky Mountain Goats, I would not consider it to be either the rifle, the binoculars, or the camp. Rather, I’d say it was the sheer guts and physical stamina necessary to get into country where the goats are; and the needed patience and tenacity to out-do the game in its own bailiwick.