The following information on establishing a hunting camp comes from Chapter 6 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

Moose-hunting is typical big big-game hunting. It usually involves getting into rugged wilderness country, considerable time, the use of pack-stock when available, and stormy, uncertain weather.

For these and allied reasons, the camp for moose-hunting is the same all-around kind of hunting camp necessary to other species; and the relationship between an ideal hunting camp and the success of a hunt cannot be over-estimated. In a poorly-organized, or ill-equipped hunting camp the minor inconveniences of dude hunters away from the comforts of home, and similar trivialities, become magnified. Details turn into major obstacles. Personnel develop “cabin-fever.” The aggregate result often is that the party turns sour, and the memories, instead of being glorious, are tinged with petty grievances.

The veteran big-game hunter knows this, and comes to take it all with philosophy and a grain of salt. The beginner learns it the first time out, and too often it spells the difference between the success of his first trip and its failure.

There are two kinds of base hunting camps for big-game. One is the camp which the outfitter sets up within the general range of his quarry, and furnishes complete for the guest-hunter. This is the type often used by the non-resident coming from a distance to the hunting country, or the local hunter who arranges with the outfitter to have everything furnished.

In such camps, the outfitter provides the camp personnel such as guides, wrangler, camp flunkey, and the cook. A permanent cook-tent, dining-tent, and guest-tents for the party are furnished. The guest-tents are usually of the wall-tent variety, 8×10-feet in size, and each equipped with a small wood-heater, lantern, and either wooden bunks or folding cots for the hunter’s beds. Such guest-tents accommodate two hunters each.

All else at such camps, except the hunter’s sleeping-bag, rifles, clothing, and personal gear is furnished. This includes riding-saddles, horses and pack-stock for the game, food, cooking-equipment, mantas, pack saddles to haul hunters’ gear, trophies, etc.

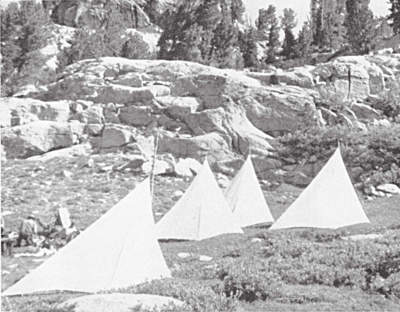

Where the hunters have to be moved to spike-camps, farther into game country away from the base-camp, they naturally have to go lighter while on over-night stops away from the main camp. The inconveniences necessary to this are accepted as part of the cost of bagging the trophy. There is, as all big-game hunters know, a direct connection between the best trophies, and getting far back into the most rugged hunting country.

The other type of hunting camp is that which the hunter furnishes complete himself, and which he hires an outfitter or packer to pack into the hunting area. The basic difference lies in the availability of outfitting services in the area the hunter wishes to hunt, and the arrangement with the outfitter.

In either case, there are basic considerations and compromises. All gear must be moved from transportation-end to the game area via airplane, truck, pack-stock, or, rarely, as in the case of getting into sheep country, by pack-board and Shank’s Pony. This involves holding weight and bulk to a minimum consistent with safety and comfort; the “packaging” of all gear into suitable shapes for hauling; and the protection of all duffel with suitable covers, against some most rugged handling, often involving wet weather and the banging-around common to packing on pack-animals.

Over the past thirty years of hunting big-game under most any conceivable circumstance, and into the most rugged country and conditions imaginable, I have gradually come up with what I consider an ideal camp for this type of hunting. The overall equipment is adequate, safe, reasonable in weight, and provides a margin for emergency.

First, let’s consider the hunting tent.

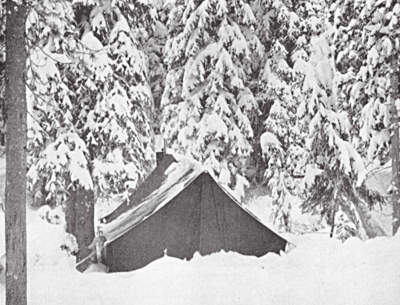

The very best tent for big-game hunting, which is co-incident with rough fall weather, is a wall-tent. No other type provides the same comfort, room, and flexibility to cope with varied weather conditions. In size, the wall-tent should be chosen to fit the number of hunters. A tent measuring 10×12 feet will accommodate two hunters, where cooking is done inside the tent. Three hunters can use this size in a pinch, but the 12×14 is better. Similarly, four men can get by with a 12×14 tent, but the 14×16-foot size is better. This size is adequate for four hunters. In larger-sized parties, use multiples of this arrangement.

Where several tents are used, keeping one for sleeping purposes only, allow a minimum of 25 square feet of floor space for each sleeper. That is, a 10×12-foot wall tent will sleep four men, if used for no other purpose. A light-weight tepee makes an ideal complement to the wall-tent, for any sized party. Duffel not necessary to the day’s hunt may be stored inside, allowing more room in the wall-tent. Any tent used in big-game hunting should be thoroughly waterproof. A single hole in the tent roof, allowing dripping, in rainy weather, or from melting snows, is enough to spoil the hunt for many men—especially if it drips over a sleeping-bag.

The first thing many veteran hunters do with a new wall-tent is immediately to sew sufficient extension onto the bottom of the walls, all the way around, so that the walls reach four feet in height. Such an addition to a wall-tent enlarges the enclosed space one-fourth to one-third, provides head-space enough to walk around, and makes the tent one hundred per cent more livable, especially around the stove-cooking area.

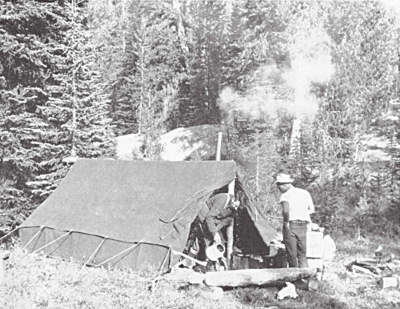

No wall-tent is complete without a stove. The two go together in big-game hunting, like the cartridge and rifle. There are several suitable sheet-iron stoves for wall-tent use, on the market. Some have ovens, some have telescoping stove-pipes, some have removable legs, or angle-iron flanges on the bottom at each corner, so the stove may be spiked to four posts driven into the ground, thereby raising the stove to a comfortable cooking level. Any good wall-tent stove should have a fire-box of sufficient length to accommodate reasonable lengths of wood. It’s a nuisance at camp to have to whack-up wood to ten or twelve-inch lengths.

After twenty years’ experimentation, I had my own wall-tent stove built to specifications, incorporating numerous needed features. This stove measures 16x16x28 inches. It is made of medium-gauge sheet-iron, except for the top which is of 3/16-inch steel. The heavier top eliminates buckling under heat, and will either hold the heat well for frying, or can be used, after polishing, to grill hotcakes, eggs, bacon, etc. The stove-pipe hole is torch-cut into the rear of the top. Four lengths of five-inch pipe fit inside the stove during transit. A 3/4-inch threaded pipe nipple is welded under the bottom at each corner, to accommodate lengths of galvanized-pipe legs—which also store inside the stove. Sides, top, bottom, and ends are welded all around, then rounded off on all edges for safety, and to prevent wearing on the mantas, while on a pack-mule.

A large wood-opening is cut into the front, as well as a draft-hole beneath. Both have hinged doors and latches of close enough fit so that the stove may be entirely draft-tight. Fuel up to twenty inches long, and of most awkward shape, may easily be shoved through the big front door. The heavy-gauge top not only maintains the uniform heat necessary to good cooking; it also holds heat well for warming the tent in extreme weather. A sizeable block of wood poked in at bed-time, will hold fire most of the night.

This stove, though quite heavy, has proven to be ideal. It weighs close to forty pounds, but exactly balances the wall-tent used on a three-man hunt, and which packers habitually cargo on the opposite side of a mule from the stove. This stove will “cook” adequately for six men, if necessary. An asbestos stove-pipe collar is sewn in the tent-roof.

Another must for the wall-tent is the gasoline lantern. The two-burner mantle lantern has long been standard. The newer single-burner lantern is almost as good, and is gradually replacing the bigger light in many outfits. For storage and hauling, nothing beats a lantern-case built of quarter-inch plywood, in rectangular shape, but in which the lantern just fits snugly all the way around. The hinged lid, complete with fastening hasp and wire-door handle for carrying, just touches the lantern-top, holding it securely. Extra mantles, funnel, gasoline filter, and an extra generator all fit inside with the lantern; and the complete outfit will haul in any kind of conveyance, including on a pack-mule, in any position, without damage.

The best sleeping-bags for big-game hunting are down bags, augmented by a couple of blankets. A good four- to six-pound wool blanket makes a down bag comfortable on the coldest nights common to hunting season. It can be handily removed for warmer weather. A lighter cotton blanket next to the sleeper, inside the bag, not only keeps the itch of wool away from the person, but can be laundered periodically. This greatly prolongs the sanitation and life of a down bag. A small feather, or foam-rubber pillow is also a necessity, and may be rolled up inside the bag.

As to clothing, I have found one generality to be true: The visiting sportsman usually finds the weather colder than he plans for while at home. Time after time I’ve been with hunters who complained of the cold of higher altitudes, shivered in their skimpy britches, or had to borrow a pair of long-handled underwear from the outfitter. This is natural. Big-game country is high country, usually wet country, and the fall seasons coincide with stormy weather and season. Many a dude finds this out, after he reaches the hunting camp.

This fact should not induce the hunter to cart along all the warm clothes he can find. Packers habitually complain about dudes bringing in “…everything but the kitchen sink,” and invariably try to “shake down” the over-equipped hunter before hitting the trail. A good basic rule in clothes is this: Have along one complete change of clothes, from the hide out. This is necessary both for cleanliness, and for changing after becoming wet. Make one such set of clothes a bit warmer than you think necessary before leaving home. Woolen clothes are better for hunting purposes than cotton or other fabrics. If allergic to wool against the hide, the underwear may be cotton.

Six pairs of socks are not too many for a big-game hunt. One pair of leather hunting boots not over ten inches high, and a pair of the new insulated rubber pacs not exceeding that height, are, I have found, ideal for any kind of big-game hunting. A woolen “stag” type hunting coat, and some kind of rain-coat, or slicker, are necessary. The newer insulated and down jackets are fine for coldest weather.

Camp tools and equipment?

Here’s my own list: Short, D-handled shovel. Double-bit ax having 2 1/2-pound head and 28-inch handle. 30-inch “Swedish” bow-saw. Belt-ax. Pack-board. Candles for emergency light. Grub boxes. Duffel bags. Cooking-kit. First-aid.

The medium-sized ax will do anything a bigger tool will, and takes but little longer. It should be sheathed in a leather case. The bow-saw cuts stove-wood faster than any ax, and because of being less noisy, is far better for the necessary logging-up of fuel while located within good game country. It, too, should have its blade sheathed in a folded-cardboard, split length of rubber hose, or even a wrapped-burlap “sheath” for protection of the blade and safety in transit.

Camp cooking-kits of the nested-aluminum type are fine where weight must be held to the absolute minimum. Where a bit more weight can be tolerated, such kits should be augmented by two heavy-gauge skillets. Stainless-steel forks and spoons are best to include, and the best table-knives I’ve ever found for such kits are those small stainless-steel paring-knives sold at the five-and-dime. Such knives are far superior to table silverware for the chore of cutting steak, peeling spuds, and similar jobs. Besides, the longer knives won’t fit inside the kit.

Where a bit more weight in the cooking-kit isn’t a nuisance, many experienced campers substitute enameled plates, cups, and dishes, for the aluminum kind. Nothing is hotter than an aluminum cup full of coffee, and the cup retains its heat long after the coffee.

To any cooking-kit should be added a long-handled fork and similar pancake-turner for the necessary “slaving over a hot stove.” In cases where weight is a small consideration, a Dutch oven of six-quart capacity is the best cooking utensil possible to have around camp. The experienced cook can do everything from fry and stew, to bake biscuits in one of these.

How does the hunter arrive at a sensible and adequate grub-list for the Big Hunt?

There are as many grub-lists as there are individuals. The camp chow should vary with the likes and needs of the person. However, there are extremes. Some men lug in the equivalent of a supermarket. Some take all frills and few staples. Others over-load on some necessities, but overlook or skimp on others.

A local doctor is not an unusual example. Doc is an avid hunter, who was delegated the chore of buying the groceries for a recent two-weeks’ hunt into a primitive region. When the party arrived and dug into the eats, they made a startling discovery. The good medic had stocked up on such items as five gallons of syrup, twelve bottles of catsup, and a gross of marshmallows; but he’d entirely neglected to include such prosaic articles as any hot-cake flour, bacon, or coffee. This big-game hunt, I was told later by one of the members, ended far more quickly than had been anticipated.

Over the last quarter-century of packing, and flying into big-game country for extended hunts, I have arrived at a basic grub-list which has proven to be nearly ideal. That is to say, it has proven entirely adequate and satisfying for most of the hunters who have been in our parties, and has a safety-margin for emergency use without being cumbersome. This list has been added to, and subtracted from, over the years. It has been used on expected ten-day hunts when we’ve been lucky and were out within the week. It has been used in country where the party has been snowed in and isolated, necessitating a two-weeks’ stay.

Never, while using this list, has a packer at our camp had to lug out an exorbitant amount of unused groceries. Never, under conditions of an extreme emergency, would we have gone hungry using this list for an entire month—assuming that at least one of the party killed a single head of big-game whose meat was edible.

This grub-list is filed away and used annually. The amounts are for a party of three men, for a ten-day’s hunt:

Coffee, 3 lbs.

Sugar, 5 lbs.

Salt, 5 lbs.

Pepper, 1 lb.

Bread, 10 loaves

Fruit juice, 18 cans, assorted

Bacon (slab), 6 lbs.

Ham (pre-cooked), 1/2 ham

Eggs, 5 dozen

Condensed milk, 10 cans (large)

Canned fruit (large), 6 cans, assorted

Canned vegetables, 12 cans, assorted

Shortening, 2 lbs.

Butter, 4 lbs.

Condensed tomato soup, 4 cans

Mayonnaise, 1 jar

Deviled ham, 6 cans

Vienna sausage, 4 cans

Chocolate bars, 1 24-unit box

Onions, 3 lbs.

Grapefruit, 1 dozen, or oranges (fresh), 2 dozen

Hotcake flour, 5 lbs.

Syrup, 1/2 gallon

Jam, 1 quart

Cheese, 3 lbs.

Tea, 1/2 lb.

Carrots, 3 lbs.

Cabbage, 3 lbs.

Potatoes, 15 lbs.

Raisins, 3 lbs.

Flour, 5 lbs.

Dry navy beans, 2 lbs.

Corn meal, 2 lbs.

Matches

Chore-Girl (pot-scratcher)

Soap, 2 bars, combination hand-wash soap

Toilet paper

Paper towels, 1 roll

Dish-cloths, cloth

This grub-list is, by weight, just about double the old Hudson Bay minimum standard of three pounds per day per man. But this list is not meant for hardy men, used to continuous bush-travel where any surplus weight represented a penalty, and a continuous supply of fresh meat was assured. Neither is it meant for men used to concentrates. Rather, it is based on a similarity of diet to that eaten at home, with adequate variety, with allowances for the normal man’s increased appetite while in the woods, and for an ample margin in an emergency.

Years ago, this particular list was arrived at in this manner, and with the help of my wife who did the home meal-planning:

“What,” I asked her, for the first time confronted by the necessity of a grub-list for an extended hunt, “shall I take to eat?”

“About what you’d eat at home,” she answered simply.

“How much?”

“How many meals will you be there? How many breakfasts, lunches, and suppers? Then multiply by the number of men going.”

Breaking the list down that way gave a fine basis for a beginning, and the ultimate list was built upon such a reasonable assumption.

In utilizing this grub-list at hunting camp, we always try to use up the perishables first, leaving such items as the dry beans, spuds, part of the bacon, and some of the canned goods till last—always with an eye towards having something on hand for delays or an emergency.

As soon as anyone of the party gets game down, the fresh-meat situation is licked. Liver, heart, and tenderloin may be used the following day. Any time thereafter a good old hunter’s stew, using the neck for “beef-stock,” may be made up, using the fresh vegetables brought along for the purpose. After several days’ hanging, an elk, moose, or sheep becomes tender enough for rib-roasts, or even steaks. The candy-bars, raisins, tinned sausages, and so forth used for lunches, can be supplemented by such delicacies as boiled tongue, ground-liver-and-mayonnaise, and other meats, prolonging the supply.

Towards the end of the hunt, the dry beans go good, after several hours’ boiling, with the remaining ham-hock. In a pinch, just boiled spuds, game-steaks, and gravy made from the frying-pan drippings is mighty filling to a hungry fellow.

Once, while we were eating huge squares of moose-steaks in Canada, I asked an M.D., “Doc, how long could a man live on just straight moose steaks, and nothing else?”

“Thirty days. And he’d come out a better man than he started.” Doc was a medic with the military for four years during World War II, and should know what he’s talking about.

I had a fine opportunity to try out the above list during the fall of 1955 on some hunters from another section of the country. I was a bit apprehensive, since my partners came from a different area (Virginia) where the eating habits are somewhat different as to diet. They left the grub-buying up to me, since we were to hunt here in Idaho. Both John and Coley were well-heeled, and could afford to cart in, and have, any amount of luxuries.

I was further surprised at camp to discover that John had once been a professional chef in a cafe. Naturally, all cooking was immediately turned over to him. Talk about a variety of camp-foods that man turned out! We killed a young elk the first day. The local season on grouse opened a few days later. What with chicken dinners, elk steaks, and the trimmings, we ate like hunters should eat.

After the trip, John remarked, “That grub-list was just about ideal. There wasn’t a thing I needed to cook with, that we didn’t have.”

Where an extreme minimum of weight is vital, such as in canoe-hunting for moose, or for hauling in a light plane, many sensible substitutions may be made. Dried fruits and vegetables can take the place of tinned items. Dried soups, and those dried “dinners” consisting of macaroni, cheese, etc., are fine. Powdered, instant milk, coffee, eggs, and potatoes cut the weight considerably. The hunter equipped with a good basic list can sensibly make the necessary substitutions, including those for the heavy stove and tent.

An instance where we had to cut weight to an absolute minimum occurred in the Cassiars of British Columbia during the fall of 1954. The closest we could set down a pontoon-equipped plane to our sheep country was five miles away. The entire spike-camp was lugged in from there on pack-boards, and we were supplied with groceries by air. Such items as dried soups, vegetables, and fruits, were dropped in the same sack as the hard-tack, pilot-biscuits, and the few tins of canned stuff.

The food was tied up in a double-canvas bag and dropped into the bush from a low-flying plane. In a drop consisting of around thirty pounds of food, we actually never lost over a pound. The cans were bent and beaten by the fall, but most of the packages of dried stuff remained intact. Where the packages had broken, we simply scooped up the contents from the clean inner bag.

One of the most important items of the ideal hunting camp has been purposely left till last. That is the “packaging” and packages in which the visiting hunter packs his duffel, food, equipment, and person, for the various methods of transportation into the hunting field. In the matter of proper packaging of expensive gear for hauling by plane, boat, or upon pack-stock into the hunting camp, I have seen more big-game hunters fail than in any other aspect of hunting.

This is due to the fact that most sportsmen don’t fully appreciate the type of rough handling, and necessary abuse their gear must undergo in order to get it into wilderness country; and a corresponding lack of proper containers available commercially, in which to package all types of gear for hauling.

In the majority of instances, the hunter, once fully realizing the problem, must make his own containers, and do his own packaging in advance.

Consider this, in the matter of packing duffel with a mule-string: The outfitter furnishes the mule and the pack-saddle, plus lash-ropes and mantas-squares of heavy canvas 6×6 feet or larger in size. The hunter furnishes his duffel. Between the two, there is a “missing link,” a suitable container. All equipment from beds, food, stoves and tents, to delicate camera equipment, clothes, and camp-tools, have to be fit, somehow, onto nothing more than two iron loops and a skeleton saddle-frame. More, it has to be tied ruggedly enough to withstand the rigors of a rough trail, often upon a mule which bucks at the sight of leather; has to be eared down to load; kicks as naturally as he brays; and has no regard for human life, limb, or property.

Despite this, mountain-country packers can and do continuously stack heavy cargoes of every conceivable content upon the poop-decks of such transportation, and have it arrive many rough miles later without breakage—if it is well packaged for the trip. For over twenty years, I have had my own duffel packed via mule-train, plane, river-boat down such rides as the famed River Of No Return, and have lost but very little outfit. This duffel has included such items as a thousand dollars’ worth of expensive cameras, prized rifles, binoculars, spotting-scopes, and so forth.

The most rugged form of transportation is, perhaps, hauling on pack-animals. Duffel packaged correctly for this type of hauling will be entirely right for most any other kind, so let’s consider the problem and the solution, as regards trail-stock:

Each pack-animal carries two “cargoes” of equal weight, on opposite sides of the saddle. Very few packers will consider hauling separate cargoes weighing over one hundred pounds, or over thirty inches in any dimension. This means that the hunter should take nothing to camp, with the exception of his rifle and possibly a fishing-rod, which exceeds thirty inches in length. Further, no single package of duffel, from stove to tent to grub-boxes, should ever exceed a weight of between seventy and one hundred pounds. And lastly, once on the trail, pack-animals are never made to stop en route for anything less than an emergency. Loaded stock must reach camp before being unloaded, or stopped no more than for the temporary tightening of packs. This rule holds despite the number of hours on the trail, rain, snow, or hell and high water. Lunches at mid-day are non-existent, except for what the person has had the foresight to stash away in his jacket pocket.

With these limitations in mind, the dude must somehow have arranged in advance of the hunt so that none of his outfit, including himself, will either be broken, wet, or otherwise ruined in transit. Here, briefly, is how to do it:

Let’s begin with the sleeping-bag. A wet bed can ruin a big-game hunt quicker than any known object or reason. The water-repellant bags of today, simply will not withstand long periods of rain or wet snow, without becoming wet—especially under the stress and “working” of tight lash-ropes. Neither will mantas or the pack-covers ordinarily furnished by the packer.

The best cover for the sleeping-bag is a waterproofed canvas tarpaulin, or “tarp,” in approximately 7×9-foot size. A tarp of this size adequately covers the bed-roll, and is best tied up with sash-cord, with an express-hitch. If this tarp is grommeted along all edges, it easily doubles as a ground-cloth, bed-cover, or even an A-tent in a pinch—simply being thrown over a pole, and staked down with ropes through the grommets along the edges. A tarp will further prevent sand getting into the bed, while camping on beaches or dry ground. It substitutes well for such chores as emergency meat-covers, camp wind-break, or light-weight manta. Mostly, it is dry-bed insurance.

For packing groceries, nothing beats a pair of light, plywood “kitchens” made especially for the purpose. Every packer has his own idea of the details and design, but basically they are rectangular boxes of approximately 26-inch length, 22-inch height, and 10-or 11-inch thickness. Some have hinged lids. Some have canvas-and-bail lids. Some are built with the inner sides concave, to conform to the contour of a mule-and-saddle. Others are equipped with slats screwed obliquely onto the front and rear edges, under which the lash-ropes, of a “swing-hitch,” go. Still others have leather loops riveted on, and which go over the X’s of a sawbuck saddle. The more fancy kitchens are often partitioned, so that the cooking-kit goes into one compartment, the canned goods in another, the Dutch-oven in a separate place, and perishable food in still another. And occasionally one sees a kitchen having front and top compartments which simply un-latch and fold down to form simple tables.

We once used one of these deluxe models, while riding a hundred miles down the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. When lunch time came, the packer kept on going with the mule-string. But the “dudes” simply stopped the kitchen-mule, unlashed the kitchens, unfolded them into tiny tables, and went to grazing on the contents, especially put up in advance for the day. Afterward, we caught up with the pack-string.

One of the fanciest sets of kitchens I’ve ever seen had a removable shelf arrangement on the inside. Cleats held a plywood shelf in each kitchen just the height of bread-loaves above the bottom of the containers. Fresh bread was handily stored below the shelves, with canned stuff on top. On the trail, the kitchen-mule could buck or roll his pack down a mountain-side without so much as denting the fresh bread. Eggs under such treatment would, of course, become omelets.

On trips where the hunter must furnish his own food, there is no better way of packaging it than to pre-load it into a pair of such kitchens. The boxes are balanced exactly as to weight, unloaded at transportation-end, and loaded without delay upon the kitchen-mule. These kitchens work equally well on a plane, riverboat, or even in transit in the automobile or pickup.

Any hunter can make the simplest kind, or have them made—simple plywood boxes of the above dimensions, re-inforced at all corners either with inside corner-cleats of quarter-round moulding, or outside metal corner-strips. A hinged lid with fastening hasp, and a couple of rope handles at the ends complete the containers. They protect the grub supply en route, and are waterproof for rain or snow while on the trail.

A fine substitute for the hunter too lazy to make his own is a pair of plywood boxes used by the military for storing and dropping fragmentary bomb-kits during the last war. They are plywood boxes, re-inforced all the way around with riveted metal. The lid fits almost air-tight upon a rubber sealing-ring. Metal side fasteners tap onto metal rails, cinching the lid down most tightly. A metal handle at each end completes the box.

These boxes are officially designated as “kit conversions for fragmentary bombs.” They would cost at least fifteen dollars each to make, but are still available at this writing, at the various army-surplus stores, brand-new, for around three dollars each. They measure 13x13x33 inches in size. Except for being but a few inches too long, a few inches too short in height, and a couple of inches too “thick,” they are wonderful for kitchens. Big-game hunters in the know are buying them for the purpose, and the various outfitters are learning how to mule-pack them “as is.”

In storing food, the heavy canned goods should all go in a layer on the box’s bottom, with the remaining space to the top filled with lighter items such as loaf-bread, fresh vegetables, carton-eggs, and so forth, making certain that the pair of boxes match exactly as to weight. The top of each box is then plainly marked “Top,” for the packer to see. He loads it with the heavy side next to the pack-animal. The boxes ride fairly well in a vertical position with the “top” parts out, if upon large animals. More experienced packers are coming to “barrel-hitch” these grub-boxes, so that they ride longitudinally along the pack-animal. They work fine if lashed in that position, even under the stress of steep, switchback trails. Further, it isn’t really necessary to manta them.

Personal gear, clothes, ammunition, camera equipment, and such should be pre-packaged in some kind of waterproof containers which will withstand rope-lashing. That means as tight as the packer can pull them—usually with his booted heel in the cargo’s center.

The best containers I’ve found for this purpose were a pair of rubber “portable ice-packs” as the military designates them. These are rectangular bags of moulded rubber, measuring 9x12x19 inches. They are equipped with carrying straps, and a folding-lip arrangement which, when buckled down, makes them entirely waterproof. I carry expensive press-camera gear in these, after anchoring it inside fitted plywood boxes. So packaged, it will stand rain, snow, and the considerable abuse which animal-packing entails.

One field instance is indicative. One of these rubber packs was once loaded as a top-pack on a Wyoming mule. It contained a two-hundred-dollar Speed Graphic, plus that much more in supplementary lenses, film, and flash-gun. While fording a deep-set creek, the camera-mule simply vaulted for ten feet. The pack was bucked off, fell in the creek, floated a hundred feet before the packer could retrieve it, but didn’t leak or injure the equipment in any way.

A few of these packs are still available at army-surplus stores, if one is lucky enough to locate them.

A similar, commercially-made pack is made by a few of the big New York outfitting houses for sportsmen. These are rectangular packs measuring 10x18x13 inches, of heavy pressed-fiber construction, strong press-on lids, and heavy leather loops designed especially for pack-saddle use. All small gear may be packed into a pair of these in advance, and simply hung-and-lashed upon an animal like a pair of grub-kitchens. Once the lid is pressed into place, they are virtually air-tight.

The rifle also should be “packaged” during transit. The best container for horse-travel is a heavy steer-hide scabbard, having a flap covering the scope and action, and which will fasten down securely yet permit quick access of the rifle. Regardless of which way the hunter mounts his rifle on the saddle-horse, it will ride with the stock-butt up. An open-ended scabbard is a constant invitation to rain, snow, or twigs falling from trees along the trail as they are moved by stock and riders. Snow, rain, or tiny twigs can easily put a rifle out of commission, especially if it is scope-equipped. A flap covering the scabbard’s open end will prevent this.

For transportation other than on a saddle-horse, one of the new plastic sheepskin lined, or felt-lined, cases which closes with a zipper is fine. Such a case prevents dust and moisture getting to the rifle, and if the rifle is gone over lightly with a good gun-oil such as Rig, inside and out, before insertion, it will remain rustproof. One of the older types made of sheepskin is an abomination in any kind of wet weather. The hide holds water like a sponge, and rusting of the rifle is almost sure to result. I once took such a rifle-case for a hundred miles down the River Of No Return by boat on a fall hunt. Constant spray from the boat’s prow, plus wet weather, kept that rifle constantly soaked. Only careful drying out and oiling every night kept that rifle from complete ruination.

Fishing-rods, too, are often carried on big-game hunts. Such rods are habitually carried as top-pack between cargoes, while on the trail. Aluminum rod-cases won’t withstand the pressure resulting from an animal’s catching them upon trees—they simply buckle, ruining the rod.

The best preventative for this is to insert a hardwood dowel of 5/8 or 3/4-inch diameter inside the case, alongside the rod. It takes a lot of abuse before such a combination can be made to fold-up.

Lastly comes the “packaging” of the hunter’s person, usually against the wet common to hunting season. There is no more grouchy, discouraged human than the hunter unused to being wet, and who cannot stay, or become dry. Here again the same “containers” which will keep the hunter dry during horse-travel, become ideal for most other hunting conditions.

In addition to the warm woolen clothes necessary to the trip, the big-game hunter needs an absolutely waterproof rain-coat. No Western mountain-man ever leaves camp without his slicker tied on the saddle behind the cantle. Storms are common to the high altitudes of game country, and, as they say in Montana, “Nobody but a tenderfoot or a damn fool ever tries to predict the weather.”

The heavy rubber raincoat is gradually being replaced with a shorter thigh-length plastic raincoat having an integral parka-hood. Such a coat of large enough size to go over heavy stag coats, and worn in conjunction with cowboy chaps, will keep the rider bone-dry. Rubberized ponchos are good, though bulky.

For keeping the legs dry on the trail, riding-chaps are a necessity. The old-fashioned sheepskin chaps, and those fancy chrome doeskin chaps all dolled up with silver conchas, and which make drug-store cowboys look so breath-taking while on the stage, or when yodeling in a western bar, are not worth a tinker’s damn for keeping one dry while on a horse. Both soak up water like a dish-rag.

For keeping dry, plain leather “bull-hide” chaps are best. An even better lighter-weight chaps for occasional use is a pair of those Western-developed lambing-chaps used by stockmen. These are shaped like cowboy chaps, but made of heavy waterproofed canvas instead of leather. They are priceless for riding in wet weather, and for breaking the bite of cold winds. They weigh only two or three pounds, and may easily be made up by a canvas-shop in areas where they cannot be purchased. They should be amply large.

Most caps and hats designed for the hunter are worthless for riding in rainy weather. The wide-brimmed “ten-gallon” hats common to Westerners are far better. They allow collected water to pour off either in front of the user’s collar, or sufficiently behind it to run off the rain-coat, not precisely down his neck, fore and aft, as with a cap.

Ray Wolfensberger, a Selway guide, once showed me how he kept his head entirely dry. He wore his big hat with the crown dentless. It looked quite like an inverted horse’s nose-bag upon his head. He’d further waterproofed the hat, the day he bought it, by painting it with melted paraffin. “Yep,” he grinned at the battered lid, “she’s five years old this fall, and never leaked a drop yet.”

Commercial waterproofing is available for tents, tarps, and other canvas containers. If the hunter wishes to make his own compound, here is a good formula using paraffin as a base. I have tents waterproofed fifteen years ago with this waterproofing, and which still don’t leak a drop after annual use for that period of time.

For each pound and one-half of paraffin sealing-wax, use a gallon of white gasoline. Melt the paraffin, and heat the gasoline to the boiling-point. Gasoline is heated, not over an open flame, but by immersing a panful into a tub of boiling water, taken outdoors away from any danger from fire. The gasoline, having a lower boiling-point, will boil easily. When it is hot, the paraffin is stirred well into it.

The canvas goods to be treated may either be immersed into this mixture, in a tub, and thoroughly worked about with a wooden paddle so that every portion is soaked; or the mixture may be painted onto the fabric with a brush while it is still hot.

Lastly, the treated canvas is hung out to air for several days prior to use. This removes the smell of gasoline.

One final item of use on most any kind of big-game hunt is a small pack-board. Such a board, about three-fourths the size of the standard pack-board, is the easiest way of carrying the light equipment necessary to foot-hunting. It is also adequate for lugging back the cape-and-horns of sheep, goat, and other game of comparable size.

So far as I know, there is no such small-sized pack-board on the market. The hunter must make his own. This, however, is simple.

Doc Wygant had an interesting one, home-made with but an hour or so of pleasant work. The frame-work was of bamboo and plywood. Three strips of quarter-inch plywood were used for the cross-bars, which set into two bamboo uprights. The board was patterned after the standard Trapper Nelson board. To get the needed curve into the cross members, two layers of plywood were laid together for each cross-bar; bent into a curve; and riveted, so that the curve stayed. These curved cross-bars were then mortised into slots carefully cut into the upright bamboo standards. Lastly, carrying straps were riveted to the upper cross-bar, and a canvas wrap laced around the frame.

The entire board weighed less than two pounds, and would carry loads of up to twenty pounds or more.

I made a similar small pack-board several years ago, and which is still being used. The frame is made something like a small ladder. The two uprights, which set edge-wise, are of 1/2-inch lumber, 19 inches long and 1 3/4-inches deep. The three cross slats are of the same semi-hardwood lumber, taken from a packing-crate. They measure 10 1/2 inches wide, and are screwed into three rectangular slots cut into the rear edges of the upright standards. The top and bottom cross slats are located 1 1/2 inches from the top, and the bottom, respectively. The third cross-bar is located in the center, giving the finished frame a ladder-like appearance.

The webbed shoulder straps are riveted to the upper cross-bar, and tied at their other ends with nylon rope to metal rings fastened to the lower ends of the uprights. A canvas wrap is laced around the frame, with the lacing at the rear away from the wearer.

For convenience, I also made a small sack the same size of the pack-board. This is attached with leather thongs tied to small metal rings sewed into the top of the sack, and thence to eye-screws set into the upper ends of the upright standards. Similar eye-screws are set along the outside length of the uprights. The load, or the sack, is laced down to these with nylon cord. The entire board weighs but 1 1/2 pounds.

While hunting, the necessary ammunition, lunch, rope, cheesecloth for covering meat, and similar items are carried in the sack. For the return trip, heart-and-liver may be carried in the sack, or the cape laced upon the board and easily brought in.

Generally speaking, each hunter should limit himself to two hundred pounds of gear, regardless of the trip. Upon weighing the entire above outfit at the air-port last fall, for a big-game hunt, we found it to be just six hundred forty pounds. This gear included groceries for a party of three hunters for ten days. In so far as grub and camping equipment were concerned, we had ample for four men, as well as a margin for safety.

As with anything else, individual tastes vary in equipment. The hunter should arrive at his own sensible conclusions. The above outfit, however, may serve as a guide. It has been thoroughly tested over many years, and under most every conceivable hunting condition.

Perhaps one of the greatest satisfactions coming from the use of such a basic, down-to-earth outfit and camp, is the repeated looks on the various outfitters’ faces as they size it up critically, and remark, “I see you’ve been around.”

There is, as the beginning big-game hunter will come quickly to know, a direct relationship between hitting it off well from the start with any outfitter, and the ultimate success or failure of a hunt. Nothing quite impresses an outfitter or packer so much as a dude’s arrival at road’s-end with a sensible outfit devoid of all frills, but composed of the basic necessities, and packaged well for the transportation facilities available.

The outfitter’s mental summing up is, “This fellow seems to be a right guy. I’m sure as hell going to see that he gets a grand hunt.”