The following information on alpine hunting comes from Chapter 12 of Hunting Our Biggest Game by Clyde Ormond. Hunting Our Biggest Game is also available to purchase in print.

Many hunters of our biggest game are middle-aged. This is due to the fact that the harder-to-get species are gradually becoming more expensive to hunt, and the ordinary fellow often has to wait until he’s comparatively well-heeled before he can go on the Big Hunt.

While waiting for that happy day, however, he continues to dream, hope, and anticipate. In his mind he envisions the time when he will be able to go, and his imagination includes only the thrilling, happy aspects of the hunting trip. He sees the thrill of stalking game, the exhilarating moment when he makes the kill, and the prized trophy—all highlights of a long-awaited experience amid the company of good men.

Nothing in the conditioning of such fellows has prepared them for such incidentals as the eternal chewing of black-flies, the arduous hiking into crags and peaks country, or any of the inconveniences accompanying the living in really wilderness country. In short, the mind is ready for the experience of the hunt, but the body is not hardened into a state of complete fitness.

Tex Purvis, a man who now outfits parties in Old Mexico, once told me in a Western hunting-camp, “Every fall the biggest share of our guests are middle-aged men. Some of them, old men. By the time they can really afford a hunt for big stuff, they’d got a pile of dough. But they’ve also got flabby muscles and a pot-gut. They come out full of piss and vinegar, to play Injun for a couple of weeks. But most of ’em simply can’t take it. We have to baby ’em along and tend them like babes in the woods. Still and all, you can’t very well spoil the illusions of a man who wants to hunt, and is paying you for it.”

Hunting such top-of-the-world country as the ranges of Mountain Caribou is a fine place for any man to find out just how good he is—as a man.

Such hunting entails hard hiking, all uphill or downhill. It necessitates breathing rarified air, to which the lungs at lower elevations are not accustomed. It involves sudden and violent changes of temperature, long distances, and hours far longer than those accustomed to at the home office. It very often entails the achievement of a basic philosophy which will not allow trivialities, no matter how aggravating at the time, to become monstrous.

I know many men who take to the high mountain country on big-game hunts, largely to see how good they are as men; and temporarily to shuck off the complexities of living too close to too many people for too long at a time, and thereby gain a perspective.

These are wise men indeed. Having been urbanized, and for so long removed from things fringing on the primitive, they recognize the greater need to return. Such men are wiser still in that they try, whenever possible, to condition themselves for the rigors of the trip in advance. If not, they take things a bit easy at first, until the old frame becomes toughened to unaccustomed exertions.

For such men, the high country offers a multiple reward. The prized trophy which they bring home is but one of the rewards. The incidental pleasures, the joys which often spring up spontaneously, the added attractions of unknown land, and the sudden juxtaposition with nature in its remaining undespoiled pattern—these often become the real gist of the happy memories.

I know men who live on level country who go big-game hunting largely for the sight of the mountains. The simple majesty of elevations ranging from valleys to the snow-covered spires is beyond the comprehension of many men unused to mountain country. Others hunt the high country to obtain that same feeling of freedom, and cutting the ties of earth, which aviators feel when up in the sky. Still others hunt the primitive areas for the opportunities they afford in a pictorial way. Many a man has gone big-game hunting, carried his camera along, and subsequently become an avid photographer. Others like the breathless solitude of vast country, unbroken by all the sounds daily associated with man.

Doc Wygant is a good example of a man who gets far more out of his big-game hunt than the mere trophy.

Doc is a middle aged-man, sparse of build and pale from his daily routine in his dentist’s office. He’s a happy, good-natured soul, whom you immediately think of as the type who’d be fun around a camp. But you’d swear Doc would break in pieces under the pressure of a good wind-storm.

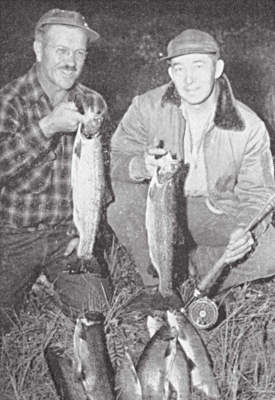

In addition to Doc’s love of hunting, he’s a fine fisherman, a fair photographer, and quite talented as an artist. He was one of our party of four on a recent Canadian hunt. He took along his sketchpad and crayons, as well as movie gear and fishing-tackle.

Once we got to the Dease Lake area of the Cassiars, this frail-appearing little man become a paradox. He was, once into the wilderness, a bee-hive of activity. Immediately Doc took over the camp chore of cooking. And talk about good food! Doc fixed up everything from fillet of sheep, to braised ptarmigan. One of these birds was a tough old hen, which Doc never could get unbent to his entire satisfaction. Henceforth, he apologized all over the place for his prize dish, “Bruised Ptarmigan.”

Between meals and periods of hunting, Doc was active as a squirrel. He took long hikes into the woods, toning up his muscles for the main event. He sketched members of the hunting party, in their homely, unposed antics around the hunting-camp. He fished wherever there was water.

As part of this hunt, Doc and I were flown by the outfitter to Cry Lake, to hunt moose. We spike-camped at the inlet, and between the choice hunting periods of daylight and again at dusk, we fished for grayling. Doc had never caught one of these beautiful Arctic fish, and set about it with customary enthusiasm. His first cast brought a 14-incher. This, while thrilling, was far too easy to suit Doc. So we paddled the flown-in canoe out into the rippling inlet-waters, anchored it, and experimented.

For twelve separate casts, and changing flies after each successive cast, we caught an Arctic Grayling each cast without a miss. Flies ranged from a #16 Red Ant, dry, to big #4 yellow nymphs.

Between fish, Doc eagerly took movies till he nearly burnt up his camera. He did use miles of film. “Oh Lord!” he’d exclaim, at each fish slashing at his rod, “Take some pictures! The guys at home will never believe this!” And after the twelfth cast, without missing a fish, Doc reeled in and picked up the paddle. “Let’s go to camp. You and I have failed. We can’t find a fly they won’t bite!”

It was thrilling just to watch that man’s pure enjoyment. He got as big a kick out of those grayling as he did from moose-hunting, later. And Doc’s thrills of that trip continue. I’ve just been notified that he’s going to show the movies of that trip to the next annual convention of the Idaho Wildlife Federation. Even though Doc Wygant killed his Stone Ram—the basic objective of that 4,000-mile trip—who can say which of the many, were the real rewards?

There are many such incidental satisfactions to big-game hunting in wilderness country. The man who has not heard the deep, lugubrious howl of a timber-wolf; who has not lain along a wilderness lake-shore which no white man has ever seen, and witnessed the majestic aurora borealis “play” like the magnificent strains of colored organ-music shooting across the heavens; or looked upward on some desolate, star-lit night as he realized he was a hundred miles from the nearest human, and was humbled at the insignificance of man. Such a man has something yet to live for.

One of the basic satisfactions a man obtains from an extended alpine hunting trip is a true conception of himself in the face of danger. The hazards involved when a man drives an automobile down the highway are probably greater than the dangers incidental to hunting our biggest game. Yet hunting big-game in remote country does entail dangers not found at home.

There is, for instance, the relatively small but constant possibility that the hunter will come upon a grizzly under the wrong set of circumstances. There is likely a greater danger that he may slip or fall while traversing jagged, semi-vertical mountains and bluffs, and either kill or cripple himself. There is, even while hunting with a guide, the continuing danger of getting too far from camp, of becoming turned around and lost, of sudden alpine storms setting in, forcing the hunter to siwash. There is the not-improbable danger of hunters becoming injured from camp-tools, or suddenly being stricken with appendicitis.

Often the dangers are incidental to the mode of transportation. Much of our real remaining wilderness country is in the far North, or amid bush country requiring the use of airplanes. Distances are long, landing-fields few, and weather conditions never the best during the fall hunting seasons. Fields become souped-in with fog. Flying suddenly has to be done “blind.” Chartered planes often act up.

The red-blooded hunter must accept these and allied hazards as part of the calculated risk. In my own experience, I have accepted such dangers as flying for hours in a strange plane and lost in fog over bush country; setting a plane afire while the entire party was aboard; and having to circle several times to find, and get through, a certain “hole” in a pass at the head of the Stikine River…and then skimming low enough over the glacial crest so that we could have dipped ice in a hind pocket.

Such risks are, I believe, far greater than the risks involved in shooting dangerous game. The man who survives them, however, has a deep, authentic appraisal of himself, as a person.

One of the greatest dangers, once the hunter actually hunts the high rugged country, is that of somehow mis-calculating so that he cannot reach camp, and subsequently has to siwash. This can handily be done from mis-judging distances and one’s strength; getting lost in storms or fog; or pursuing game too far.

One of the best safe-guards against such a possible emergency is some kind of condensed food. No hunter should leave camp in such country without some kind of emergency ration, to tide him over should the need arise.

Field-rations like the military used during World War II are good, though on the heavy side. Pinole, such as the early Indians used, is powerful though light. This emergency food consists largely of parched corn, doctored up with brown sugar, and dried-and-hammered into powder. Indian runners used to travel days on end with nothing except a bag of it. Pemmican, or jerky, is good. Raisins are strong in energy for their weight. Chocolate bars contain quick energy, too. Many Canadian Indian guides peel off the meat from that first roasted slab of moose or sheep-ribs, put it into the pouch, and it becomes either traveling, or emergency rations.

A small envelope or paper of tea is a most useful complement to any condensed food, and often may be brewed in the food-container. Tea not only “swills it down,” but gives the needed warmth.

I hunted for years with an experienced elk-hunter who would not leave camp without a small paper-wrapped package of salt. This was his survival-insurance, should he ever have to siwash, or become suddenly lost. He depended upon his woodsmanship and hunting skill to provide something by way of meat to be salted.

Only once was I with him when we had to siwash. We killed an elk six miles from camp at dusk, and there was nothing else to do. That night we ate the remaining raisins from lunch, plus strips of elk-liver and heart toasted against the all-night fire, and after the meat had been thoroughly cooled out in the ice-bound spring at the head of water. These strips, incidentally, tasted mighty fresh and gamey; but they were far better than no strips.

It’s a good notion to carry a paper envelope of black pepper along with the salt, if the emergency ration is to be freshly-killed meat. Fresh meat often gives the hunter what is known in the Selway as the “Rocky Mountain Quick-Step,” or in Wyoming’s Jackson Hole country as the “Jackson Jumps.”

Another fine emergency ration which can easily be carried in the ruck-sack, or light pack-board, is dried, powdered soup. This can easily be heated up in the same small tin used to brew the tea later on. It’s powerful, tasty, and filling.

A somewhat amusing incident in which this type of food suddenly became vital to two hunters’ survival, occurred on our 1954 Canadian hunt. This incident was not at all funny at the time, but is typical of the kind of unforeseen emergency which often arises in big-game hunting.

After circling a band of Stone Rams far around the mountain range from where they were first spotted, two of our party and the Indian guide found themselves many miles from camp. Luckily, both hunters connected, as the sheep took off. Their Indian guide, with the understandable mis-conception of the aborigine that surely the white man who had subdued his race, must have at least the woodsmanship of himself, made a suggestion. What he tried to point out was the fact that they were at the time closer to the big base-camp where we’d set down with the plane, than back to spike-camp from which we’d hiked in to hunt rams. Since this was true, why not let him cape out the rams, and tote the trophies back to base-camp, while the hunters went back to spike-camp? He, the guide, would make the circle back to spike-camp for them, the next day.

This Indian had been to a mission school, and could talk broken English. He could not, however, explain well enough to keep the hunters from getting thoroughly confused. He indicated a certain ridge and basin, evidently thinking to show them a short-cut. The result was that the hunters, a doctor and a Northwestern Airlines pilot, tried to follow directions; but they wound up in entirely strange country, and completely lost.

The two did, though, have emergency food. This consisted largely of dried soup, packaged in heavy tin-foil. This product had been purchased in Canada especially for the purpose, and was labeled in French.

Neither hunter had more than a long-forgotten high-school acquaintance with the language. But they did interpret one boldly-lettered piece of instructions into usable English. Roughly, it translated into this sage piece of advice: “Important! Detach the envelope from the soup!”

The two came out of the minor emergency with nothing worse than hungry bellies and a night’s siwash. The more they talked about it, the more one aspect of the affair came to strike the doctor as completely hilarious.

“What,” he roared, “would have happened if neither one of us could have deciphered that French? Just imagine! Two hunters, lost in the wilds. Both with a little horse-sense. And with emergency rations.

“But I can just see the tragic head-lines: ‘Air-Line Pilot and Medic Starve To Death! Neither Spoke French…And Didn’t Detach Ze Envelope From Ze Soup!”