The following information on quick firing and running shots comes from Rifles and Rifle Shooting by Charles Askins. Rifles & Rifle Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

A deceptive glamor lingers about the days gone by. Without reasoning the matter out, many of us have an instinctive belief that there will never be another class of riflemen like the pioneers of a hundred years ago. However, it is my belief that the real rifleman is yet to be developed, and his time will shortly be here.

I do not wish to reflect on the skill of the man with the flintlock or to insinuate that the Kentucky riflemen couldn’t shoot; there is no one today who could equal their performances with the weapons they possessed, nevertheless, the strict limitations of their arms necessarily governed the ability of the men who used them. Forty-eight inch barrels as thick at the muzzle as at the breech, loaded with a small round bullet, stocked with a piece of wood that was a mere handle, and a set trigger lock, furthered nothing but deliberate work at short range.

While some of these woodsmen could undoubtedly kill game in motion, since they had opportunities to practice immensely greater than any we are blessed with, yet they never took a running shot from choice. Indeed they were extremely partial to shooting from a rest whenever that was possible. Who could say that we would not do the same if we were given a rifle with an accurate range of but one hundred yards, that fizzled, flashed in the pan, and hung fire before starting its projectile on the way.

Even in the days of the Hawken rifle from 1840 to 1870, plainsmen were in the habit of carrying sticks to rest the rifle upon. Those were times when a bullet had to be placed right to do the work. Take it along down to within the past decade and the measure of a rifleman’s skill was still his ability to bunch a series of shots, deliberately held. I believe the record for this kind of work is ten shots off-hand in a four and a half-inch circle at two hundred yards. Since the limit of accuracy in the rifle has about been reached, this is not likely to be excelled very much but even the man who can do it may not be a rifleman in the modern sense.

The twentieth century rifleman must not only shoot straight but shoot fast. His standard of excellence will not be ten shots in a four and a half inch delivered in half an hour, but ten shots in an eight-inch, all fired in ten seconds. He will kill his game as he comes to it, running, standing, and perhaps flying. It is now not beyond reason to anticipate a time when the hunter will deliberately start his deer to running in order to give it a fair sporting chance for its life, having the same contempt for a potshot that the shotgun expert has to-day.

I have spoken of this modern rifleman as “shotgun trained,” not so much because he has been accustomed only to the scatter gun, as because he has developed the shotgun style of aiming to a point where it can be used with a rifle. Shotgun shooting means pulling trigger the instant our piece covers the point of aim, never dwelling and never taking a second sight, and rapid rifle fire is exactly that, no whit more and nothing less.

Our instructions heretofore have had reference to deliberate shooting, a careful and gentle manipulation of the weapon, an even and delicate pressure of the trigger, a cold control of nerve that sent the bullet on its way only when the aim is sure, time not being considered. Such work is furthered by heavy hanging barrels, set triggers, miniature loads, and “micrometer” appliances generally, but these are not for the student of rapid firing and running shooting.

The rifle for rapid firing should have shotgun weight, shotgun balance, shotgun trigger pull, shotgun fit, and the sights must be such as can be caught instantly without effort in alignment. The hands grasp the piece firmly, not with the rifleman’s loose grip, but the left arm pushes forward while the right draws back, and the trigger is pulled by transferring the drawing back force to the trigger finger, and not by any conscious crooking of that finger. The moment the bead covers the mark the bullet must be under way, be the aim good or bad.

The skill in this kind of work comes, not from being able to hold the weapon as though in a vise, but to swing true to the mark, and to let-off in the hundredth part of a second, no conscious thought whatever being given to the pulling. We need not hurry our movements, indeed we can make them with mechanical regularity if we like, but just as sure as the bead rises to a certain point or swings to a certain point, the bullet must go.

If we hesitate, dwell, or try for a surer aim the practice is useless, and the opportunity is gone if it is running game or a disappearing target.

The training for deliberate firing is to shoot with a rifle hanging “dead,” taking the utmost care not to disturb it by the pressure of the trigger. Neither does it matter how we get on the mark or how much time it takes. On the contrary rapid firing means the making of perfect movements. The measure of skill at a still target lies in the ability to move the sights upon it with mechanical exactness and to time the pull to the motions of the gun.

Much of the training for rapid firing can be accomplished with an empty gun; simply sight and pull trigger, keeping it up until muscles and nerves become thoroughly obedient to the will. Of course the marksman will desire to prove his progress pretty frequently by using bullets in his gun. Naturally results will depend greatly upon clever trigger pulling; sometimes the novice will let-off too soon and more often too late.

In the beginning the same accuracy must not be expected as could be secured by deliberate firing. Ten shots in a two-inch ring at twenty-five yards are pretty good. Progress, however, will generally be so rapid as to elate the rifleman highly, and in the end he may decide that he can do finer work in this style than any other.

As to the rapidity of fire, ten shots in twenty seconds is fast enough in the beginning. All this kind of work presupposes a repeating rifle, and it follows that the model of this will ultimately govern the speed with which it can be shot. With a lightly charged automatic ten shots are possible in ten seconds, all well aimed after the manner detailed; with a bolt-action gun ten shots in twenty seconds would be good, and the pump and lever would come somewhere between. Heavy hunting charges will make the marksman slower, since he must recover balance before firing again. However, this is to be said for the rapid fire system of aiming,—recoil is never felt to anything like the same extent as when the rifle is held for a deliberate aim. So true is this that most people will get their best results from light rifles, with heavy charges, when shot with the rapid fire aim.

With a hunting rifle, shot rapid-fire, it ought to be possible for the average man to place his ten shots in an eight-inch circle at one hundred yards; many can do better than this. I have seen the ten shots go into a six-inch, using a .30-30 rifle, the majority going into a four; time fifteen seconds. The man who can do this is a real game shot and a real rifleman in the modern meaning of the term.

Unquestionably the utility of quick-time firing lies in enabling us to shoot at moving objects or those that are liable to move in a deuce of a hurry. The soldier may see a rifle settling to an aim upon him and plug its owner before the latter can fire, or the hunter may catch a great buck as it tops the brush in one long leap, and would then be gone. Half the shots that a hunter wastes are thrown away because the game is running, or he is hurried out of his accustomed time for fear it will run, and the soldier of the future who cannot shoot true and quick will find himself in the role of the proverbial billet that catches the bullet.

Military authorities have arranged for rapid fire, skirmish runs, and disappearing targets. Civilian riflemen can get the disappearing target on the range by running it up out of the pit as usual and leaving it there a certain length of time. Or he can exercise his ingenuity by inventing some other kind of a disappearing target.

However, the bulk of his practice should be at a running target.

Running Targets

It is not to be disputed that the best practice in shooting at a running target would be firing at actual game in the woods and hills, but this is not practicable unless a man lives in a country teeming with game and shoots a great deal. The ordinary sportsman who takes a yearly outing of a week or two, killing the number of bucks that the law allows, might keep it up for twenty years and know little more of shooting on the run in the end than he did in the beginning. It follows then that if he is to acquire any skill at this branch of rifle firing, he must find some artificial substitute for the living animal. Usually this takes the shape of a running deer or a running hare—a wooden or iron plate, cut into some semblance of the game it represents, and made to travel across the range on a taut wire.

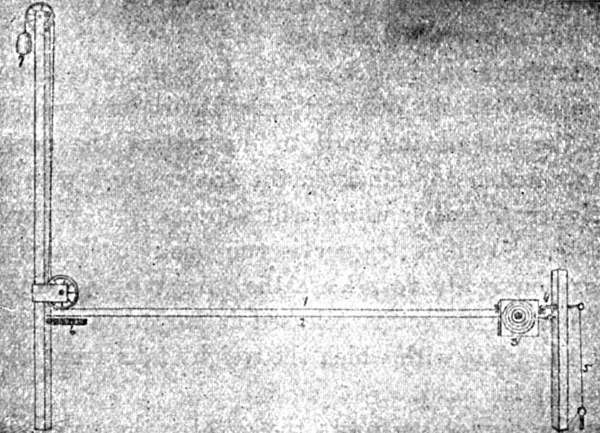

A running target that can readily be constructed by an amateur and used without the assistance of a helper is made as follows: Erect two poles of such height as you wish the target to run, place them as far apart as they are high since the altitude of the poles governs the length of the run. Stretch a good stiff, straight wire between them at the desired elevation. The target itself can be made of a block of wood plated with iron, or a simple block of wood could be used if the marksman did not object to replacing it pretty often. Bore a hole through this block of such size that it will slip freely along the wire. Fasten a cord to the target, this cord to be run through a pulley a trifle higher than the wire, thence over the top of the pole across another pulley and down to the ground where a weight is attached. Fasten the pulling cord to the upper corners of the block so that it will be held right side up when being pulled—it might possibly be necessary to attach a weight to the bottom of the block too if it betrays a tendency to turn over when struck.

In using the target slip it along the wire from one post to the other; this will raise the weight at the end of the cord to the top of the post. Now fasten the block to the second post with a trigger or catch which will slip easily. A cord fastened to this trigger is run back to shooting position ready to release the target by jerking. When the target is released it is jerked across at the speed with which the weight falls from the top of the post.

The higher the posts the greater the speed of the target at the end of its run—friction aside it would move sixteen feet the first second and thirty-two the next. By making the poles high enough or the run long enough a speed would be attained of nearly the rate at which a bird flies. This target is only adapted to small bore rifles; large weapons would shoot it to pieces, or the necessarily thick steel would entail too much weight and friction.

By having an assistant the marksman can stand back any distance he likes until he attains a range that will force him to hold ahead from one to two feet in order to land on the target. We will go into the speed of running targets and the distance they must be led presently.

Another running target can be made by using a cash trolley carrier, exactly the kind seen in department stores. This could be operated precisely as in the store if desired, the target of heavy pasteboard being swung some distance beneath the carrier to prevent wild shots from tearing up the running gear. By starting the carrier well above the ground it will gather sufficient momentum and can be run level where shot at.

Perhaps a better scheme is to dig a trench through which the trolley wire can be stretched beneath the surface where the carrier cannot be touched by bullets. The target of cardboard is then mounted on upright wires high enough above the carrier so that it will be well exposed to view when moving. Motive power is supplied by a geared bicycle wheel with crank attached, the cord from the carrier being wound over the hollow rim of the wheel. Where clubs did not object to the expense a small gasoline engine would supply the necessary power. The carrier should have a weight swung beneath to keep the target upright. If well made and running with little friction this bicycle-power can be given a velocity of fifty feet a second, approximating the speed of a bird on the wing. Of course it can be moved as much slower as desired.

Now in shooting at a running target with a rifle we are going afoul of the same problems in lead that the shotgun has made us familiar with. To be sure a high velocity bullet has a much quicker flight than the small pellets from a shotgun, nevertheless the marksman who thinks he can center a running target by holding dead on the bull has another guess coming.

To begin with let us take up the accepted method of running shooting with a rifle. We are told in the first place not to cover and swing rapidly past the mark as with a shotgun. Such swing cannot be governed finely enough for the single missile, hence it must be at once conceded that no gain can be made on the target by the swing of our piece. On the contrary the rifleman must align his sights in front of the moving object, steadily and rather deliberately, so timing his movements that as the rifle reaches its proper elevation it will be pointed the correct distance ahead to intercept the mark.

Some point the rifle still farther ahead, stopping the weapon and holding it still while waiting for the line of sight and path of the quarry, to converge. Whichever system of sighting is used, and the first is the best, it is quite evident that full allowance must be made for the time taken by the bullet in transit plus the time from the pulling of the trigger to the issue of the ball from the barrel.

Given the speed of our mark and the time of the projectile over the course it is a matter of simple calculation as to how much lead should be given in order to connect. I have had experienced hunters tell me that they simply held in front of a fleeing buck, pulling as the sights “filled;” on the other hand Van Dyke speaks of holding an entire jump ahead of a deer and centering him. We will see who is right. These calculations are made for an animal running at right angles to the line of fire, which of course he might not do, and if moving off at a gentle angle the “sight filling” would be all right.

Take our highest velocity rifle, the ’06 Government, and the time of the bullet’s flight over a 200 yard course is .244 of a second. Add to this one-fiftieth of a second, the average time for pulling trigger, action of lock, and bullet through the barrel, and we have .264 of a second as the elapsed time from our mental calculation to the landing of the bullet. Remembering that a man can run thirty feet in a second we will have to grant a deer a speed of at least forty feet. Now admitting that the beast is moving at that rate, he would cover ten feet while the bullet was reaching him, or with the slower .30-30 bullet fourteen feet. Van Dyke shot a much lower velocity projectile than either of these, and no doubt he was perfectly correct in estimating a lead of sixteen to twenty feet for a running deer at two hundred yards.

A race horse can run a mile in one minute and forty seconds or a little better than that. This means fifty-three feet a second, and while I think the race horse the fastest animal living, yet I believe that an antelope would cover fifty per second, which at a range of four hundred yards would carry him twenty-eight feet while the bullet was traveling to him. We can thus see that shooting running antelope at a quarter of a mile is not so easy as some people would have us believe.

Of course deer and other animals sometimes run at a gentle canter, but even a man walking across the range at four miles an hour at a distance of two hundred yards, would be missed if we held square upon him. Considerations which may be inferred from the above reduce the range at which running game can be killed with any certainty to one hundred yards, or a trifle over. In my experience I have never seen but one deer killed running at over two hundred yards, and then there were four moving single file, head to tail, and I doubt if the marksman knew which he held upon.

Coming down to our artificial running target, and shooting at the accepted range for this work, 100 yards, when the mark is traveling at the rate of 10 feet per second the lead should be 1.16 feet; 20 feet per second, 2.32; 30 feet per second, 3.48; 40 feet per second, 4.64; 50 feet per second, 5.80; 60 feet per second, 9.96, These calculations are made for the Government rifle with a muzzle velocity of 2,700 feet; ordinary sporting weapons would require considerable more allowance. Moreover if a man were slow on the trigger or dwelt on his aim the Lord knows how far ahead he would have to hold. These figures are for the fiftieth of a second for pulling and time out of the barrel, and that is pretty fast.

The English style of running deer shooting is to fire two shots, a right and left, while the mark is traveling about sixty feet, at thirty feet a second. The number of shots we might fire would naturally be limited by the velocity of the mark. The character of weapon we used would have its influence, too. At the given rate of speed and distance under fire, an automatic ought to get in three shots, a lever-action rifle two, but I doubt if the average rifleman with a bolt gun could do better than fire the one shot.

This is not a treatise on deer shooting, yet a word on the subject. A buck at full speed, especially when first sprung, bounds high. It will not do to attempt to hit him while he is rising or even at the height of his leap; hold low and in front, about where he will alight, for he always seems to remain at this point for the greatest length of time. Even when the animal is running straight away hold rather low—his apparent line of “flight” invariably appears to be higher than it really is, what impresses the eye being the top of his bounds where he is in plainest view.