The following information on .22 caliber Smith & Wesson Hand Ejectors comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Back in the Eighteen-eighties, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company designed two cartridges to supplement their staple .44-40. They were identical in length but smaller in caliber and were known as the .38-40 and the .32 Winchester, the latter also being designated the .32-20 because of its powder charge. With its 115-grain bullet, the .32-20 was found to have a devastating effect on woodchuck and other small animals and some hunters took to using it for deer.

As late as 1900, a benighted market hunter boasted to the editor of Recreation magazine that he had killed over 300 deer with the cartridge, for which he was properly rebuked. But the feat was not so remarkable, assuming that the braggart had an ample deer population to stalk. From a ballistic standpoint, the .32-20 was far ahead of the small-caliber muzzle-loaders that provided the venison for homes in the first half of the Nineteenth Century.

The Colt Corporation adopted the .32-20 for its single-action soon after the cartridge was developed and it served very well for those who recognized its limitations. Of course it never was popular in the far West, and neither gun-toters like Billy the Kid nor man-hunters like Pat Garrett and Bill Tilghman were addicted to it, but that was a good many years before Smith & Wesson brought out its .32 Winchester Hand-Ejector in 1899.

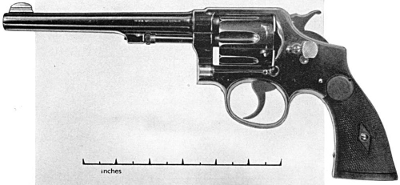

A twin of the .38 Hand-Ejector, it was built along similar lines and went through the same stages of development. No forward cylinder yoke locking device was built into the first model, of which 5,311 were made, but one was added on the 1902 model as was done for the .38 Special. It had the same rounded butt and was supplied in barrel lengths of 4, 5, 6 and 6 1/2 inches.

The second or 1902 model ran from 5,312 to 9,811, and with minor improvements to the locking device, added in 1903, the series was continued to 18,125. From that number up to 22,436 it had an improved cylinder stop working on the reciprocating principle and was known as the Model 1905. In 1909 it was further improved by a rebound slide which operated upon the recovery of the trigger between the hammer foot and the frame, encasing a coiled wire trigger spring, and the series continued in that form from 22,247 to 45,200.

On December 17, 1909, a third change was made in the model, involving alteration of the hammer at the foot, forward of the rebound seat, so as to engage the notch in the trigger for double-action throw. This series ran to serial No. 65,700, and the square butt made its appearance somewhere in that last sequence.

A fourth change was made on May 21, 1915. This involved utilization of a leaf spring, located in the side plate with head projecting between the hammer face and the frame when the hammer rested at rebound, as a hammer block. The block could be withdrawn from its normal position only through the full rearward action of the trigger at the instant of firing.

With serial No. 81,287, the model began to be produced on September 2, 1919, with a heat-treated cylinder; and from June 2, 1922, starting with serial No. 109,161, it had a square-cut rear sight, a flat top strap and a flat top front sight. Front and rear tangs were corrugated for a better grip on the target model, and after August 14, 1923, the trigger also was corrugated. From that date forward the model has remained unchanged except in inconsequential details.

The year 1902 was productive of another Smith & Wesson revolver. Daniel B. Wesson, the old inventor and designer of arms, may have felt that his work was drawing to a close and harked back to the first model revolver with which his firm had achieved success. When he had finished his drawings and translated them into metal, he had in his hands the first Smith & Wesson .22 caliber multiple shot arm that had been made in 23 years.

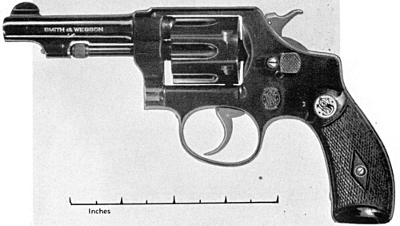

The weapon was not prepossessing, being nothing more than a tiny pocket revolver built on the hand-ejector principle. It had a seven-shot cylinder and incorporated the forward cylinder locking device already noted as having been patented December 17, 1901. With a grip which would accommodate no more than two fingers of the average hand, it was too small to be classed as a target arm, and it was made in barrel lengths of only 2, 3 and 3 1/2 inches. As in larger models, the frame bolt was operated by a collar-button-size thumb piece in the rear of the cylinder and on the left side of the frame. The gun weighed only 9 1/2 ounces.

Mr. Wesson had planned to use the .22 long rifle cartridge in the little revolver, but when one was fired the others worked loose and prevented the cylinder from rotating. To counteract this defect, a cartridge was developed which was known as the Smith & Wesson Long and which differed from the .22 long rifle only in that it was slightly crimped. The combination worked perfectly, but the model did not have a wide sale. It was supplied in both blue and nickel finish and with rounded, hard rubber grips, but the serial numbers run only from 1 to 4,575.

A second model appeared in 1906 in which the rear cylinder lock was discarded and the forward lock was operated by a knob at the forward end of the extractor rod. It was available only in rounded grips, with barrel lengths of 3 and 3 1/2 inches. The .22 long rifle cartridge had been so improved by 1906 that it could be used in this model without danger of jamming. Serials run from No. 4,576 to No. 13,950.

Model Three of this type was introduced in August of 1906. Insofar as was possible with a revolver of such light weight, the manufacturers had endeavored to make it a target arm and it could be had in barrel lengths up to 6 inches. Its square butt was still too small to afford the average hand a steady grip. Hard rubber and plain walnut grips with gold monograms were offered, and it was fitted with an adjustable rear leaf sight like that on single-shot pistols. Various lengths of the removable blade could be utilized to suit the taste of the individual shooter. The rebounding and blocking hammer used on larger models also was incorporated into this model. Another improvement was effected in the cylinder stop, an elongated stud slot being made to allow the trigger to catch in recovery. Altogether, everything was done to make such a light weapon accurate, and the public’s acceptance of the gun is reflected in the serial numbers, which ran from 12,951 to 26,154. It was still being sold as late as February, 1915, in spite of serious competition from the Bekeart model, next to be discussed.

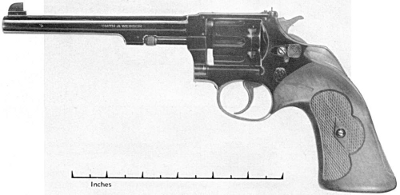

Incentive for the next development in small hand guns came from outside the Smith & Wesson plant. Phil B. Bekeart was a San Francisco firearms dealer and for some time prior to 1908 he had been urging the firm to produce a heavier type of .22 revolver. He granted that the small .22 then being put out was a nice plaything for shooting at tin cans, but he wanted something that would compare in accuracy with the .22 single-shot pistols.

When asked to be more specific, Mr. Bekeart suggested that the lines and design of the hand-ejector .32 be used as the foundation for a gun to shoot the .22 long rifle cartridge. All that needed to be done was to take a .32 barrel blank and a .32 cylinder blank and bore, rifle and chamber for the smaller caliber, with appropriately reduced extractor and a hammer geared to rim fire cartridges and hitch them to a frame as then constructed. The firm thought it over and may have built an experimental model or two; then the report was made that it would be an expensive undertaking and did Mr. Bekeart believe that the demand for the new gun would justify putting it in production?

Mr. Bekeart was so sure that he ordered a thousand of them at the prevailing rate to dealers with the understanding that he would pay for them as the demand increased. This clinched the deal and in due course of time Mr. Bekeart received his thousand .22/32 revolvers. That was around 1908, according to Colonel Hatcher, but, production on a larger scale did not begin until June, 1911.

The Bekeart model, designed for target shooting, is fitted with adjustable sights. Known officially as the .22/32 Heavy Frame Target Revolver, it has a flat face hammer which strikes a firing pin, and which in turn hits the cartridge at the top. The tang is cut near the butt to make a shoulder for extended square butt wood stocks of sufficient size to make a mansize grip. It is made only in a 6-inch barrel and in blued finish, but you have your choice of square butt, extended length stocks, or stocks similar to those on the .22 Perfected Model Single Shot Pistol. Its 23-ounce weight was considered adequate for a .22 up to recent years.

It is fitted with a Patridge sight and a square-notch adjustable rear sight. Up to a few years ago it was advertised to group in a 2 1/2-inch circle at 50 yards, but it now groups in a 1 1/2-inch circle at that distance due to improvements in cartridges—in a machine rest, of course. It is a six-shooter but is not designed for hi-speed cartridges.

Collectors need not look for a Bekeart revolver with a low serial number, for they were numbered with the .32 hand-ejector model which already had a good start when the .22 was first produced.