The following information on early Smith & Wesson single action revolvers comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Had Smith & Wesson not been so busy filling the enormous Russian order, they might have taken the time to popularize their product with the hand gun users of the West. But they were otherwise engaged and hence allowed the Colt concern to walk away from them with its Peacemaker .45 and Frontier .44-40. When they attempted to invade the territory west of the Mississippi they found the population pretty well sold on the Colt idea, in spite of the fact that the S&W could be emptied and reloaded in a fraction of the time required for the Colts.

But lack of selling effort was not the only reason for the S&W’s indifferent acceptance by Western gun-toters. In the numerous ructions and imbroglios which took place in the wide open spaces, occasions frequently arose which called for finesse rather than straight shooting—the prime desire being merely to maim or disable an opponent rather than send him up to be planted on Boot Hill. In such instances it was found that the comparatively fragile Smith & Wessons were not suited to the operation known as “pistol whipping.” After being employed as a bludgeon, the S&W generally exhibited a spavined joint at the junction of frame and barrel and had to be sent back to Springfield for repairs. The owner then had to refrain from hostilities pending its return, unless he was fortunate enough to have a spare gun. From the kind of encounters just described, the solid frame Colt emerged quite undamaged.

The Smith & Wessons probably excelled the Colts in shooting qualities, for they were chambered closer. But the black powder cartridges of either weapon fouled them so badly that they were poor target arms after a few rounds had been fired. Undoubtedly the Smith & Wesson was a much sweeter shooting arm, because of its lighter powder charge, yet it was still powerful enough to subdue a man if he were struck in the arm or leg instead of “dead center.”

The larger hammer spur of the Colt appealed strongly to belligerent Westerners. It was easy to find when the owner was in a hurry, and permitted him to shoot a split second faster than with an S&W. That fraction of a second spelled the difference between success and failure in an engagement otherwise even.

The Colt corporation gained another advantage from S&W’s preoccupation with the Russian order by getting into large scale production on smaller caliber pocket revolvers. It led off in 1870 with its rim fire “House Model” .41, and followed up with .32’s, .30’s and .22’s.

Smith & Wesson were a little contemptuous about these models, for they believed they were about through with rim fires and had quit manufacturing their old stand-by, the .32 tip-up, in 1874. However, the Colt firm came out in 1875 with its New Police models, shooting the .32 Short and Long Colt, the .38 Short and Long Colt and the .41 Short and Long Colt center fire cartridges. The New Police arms were an improvement over the company’s previous efforts, and Smith & Wesson had nothing at the moment to match them.

For the time being, they ignored the .32 and .41 caliber arms, probably figuring that the average man would prefer a .44 to a .41 if the price were the same, and they concentrated on getting out a competitor for the .38, which was showing the biggest sales.

The .38 Short Colt centerfire cartridge was built to fit a chamber of the same bore as the barrel. It held a powder charge of 18 grains and a round-nose, shouldered, hollow-base bullet of 130 grains—with outside lubrication, of course, as that was the only kind then in use. The bullet was .375 or thereabouts in diameter, although it could be shot in revolvers using the Long Colt, which calipered .358.

Basing his experiments on the laboratory records of the .44 American and Russian cartridges, Daniel Wesson designed a cartridge which was known as the .38 S&W. The shell tapered slightly from base to mouth and was made to crimp over the bullet as in the Russian cartridge, thus leaving no narrowed shoulder for the dissipation of explosive gases. The bullet’s true caliber was .36 and it weighed 146 to 150 grains. Following the formula which had yielded such excellent results with the .44 Russian cartridge, it was propelled with a powder charge of 14 grains. As originally designed, the bullet had a hollow base and a nose considerably blunter than the later designed Colt Police Positive .38. Its velocity was slightly lower, 579 f.s. compared with 608 in the Short Colt, and 108.2 ft. lbs. to 107 (A. L. A. Himmelwright’s figures). In accuracy it was far superior to the Short Colt.

Having designed a cartridge, Smith & Wesson proceeded to build a revolver to accommodate it. The result showed clearly the influence of the Russian Military model, with which they were so well satisfied, though of course it was reduced in all dimensions from the .44. The standard 3 1/4-inch barrel made it convenient as a pocket weapon, but it was available also in a 4 or 5-inch barrel length—in which case it was a pocket gun only if the tailor collaborated. The cylinder was chambered for five cartridges and like all the revolvers made after the ’60’s, was fluted.

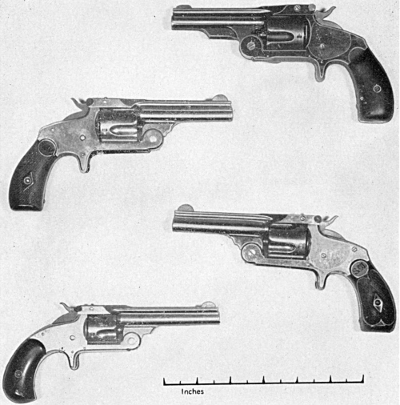

Smith & Wesson single action, .38 Second Model (First Type) Revolver.

Smith & Wesson single action, .38 Second Model (Second Type) Revolver.

Smith & Wesson single action, .32 Revolver, .32 S&W Center fire cartridge.

Sights on pocket revolvers could not project very far without constituting a hazard on the draw. On this first .38 model, and indeed on the other jointed-frame revolvers of the same caliber which followed it, the rear sight was a V-notch cut into a lug which was part of the barrel catch. It was not very wide, and with a narrow blade front sight only 1/32-inch in thickness it gave very poor definition except in excellent light. But little attention was paid to sights on pocket revolvers in that early day and apparently people did not expect them to do fine work at a target.

According to the late Henry Walter Fry in The American Rifleman, the .38 Smith & Wesson cartridge “has the sinister reputation of having killed more men in cities, not of course on the open cattle ranges, than all other revolver cartridges put together. It was before the advent of the automatic, the cartridge for the gangster or gunman’s revolver.” This may very well have been true, considering the number of revolvers which various arms manufacturers either designed to shoot the cartridge or adapted to its use. No onus attaches to Smith & Wesson revolvers because of the reputation acquired by the cartridge for which it was created. It is a known fact that early gangsters were satisfied with any kind of weapon for the touch-and-go shooting they had to do, and they were never anxious to spend the additional amount required to buy high-grade hand guns.

The First Model .38 single-action Smith & Wesson went into production in March of 1876 and 24,633 were produced up to 1880, when slight changes were made in the ejector.

The extractor gear on the First Model .38 was substantially a replica of that used on the .44 American, with a hollow lug on the lower side of the barrel containing the spring and column which released the extractor. This lug was eliminated from the barrel in the Second Model, which appeared in 1880 with serial numbers starting at 24,634. The improved extractor permitted the cylinder to be taken out with a straight pull. Later a straight thread was raised on the axis column which engaged a tiny notch on the lower edge of the barrel and held the latter in closer conjunction with the cylinder, thus minimizing the escape of powder gas between the two. The cylinder was revolved to the left for disengagements. A patented safety device released the cylinder at half-cock so that it would revolve freely until the hammer reached the full-cock position.

Factory records do not show at what serial number the second improvement was made, but the so-called 1880 Model was manufactured until 1891, terminating with serial No. 108,255, when it was superseded by the Third Model (1891)