The following information on the Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector Models comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

The Colt Corporation had no basic patent on its hand-ejector revolver. As mentioned previously, the system had been anticipated in the Moore revolver during Civil War times, and the patent under which the 1887 hand-ejector Colt was manufactured merely covered the latch which permitted the split frame to be swung apart for ejecting and reloading. It operated by pressure to the rear and consequently reversing the process was a simple matter. Smith & Wesson was granted a patent on the modified system July 16, 1895, and the following March brought out a .32 caliber revolver under the new authorization.

These first hand-ejectors followed S&W precedent in that they had a top rib along the barrel, which was threaded to screw to the frame. The side plate was inserted from the right, instead of from the left, and the yoke containing the cylinder swung to the left as in all later models. It was a six-shooter and would accommodate the .32 Colt center-fire, the .32 S&W and the .32 S&W Long—if you weren’t particular what happened to the chambers.

One would naturally expect that the .32 would be followed by guns of other caliber using the same system, but nothing of the kind took place until March of 1899. In the meantime, several chapters of United States history had been written.

The Spanish-American War was an informal sort of brawl which started without much enthusiasm on either side. Nobody seems to have given much thought to preparedness during the two months or so which elapsed between the destruction of the Maine and the actual declaration of war by Congress. Speeches were made, flags were waved, and chests were thumped, but precious few contracts were let for arms and ammunition. As a consequence, this country began the war with what little it had on hand. If our opponent had been more than a third-rate power, we might have been badly embarrassed.

Only our small regular army and Marine Corps had repeating rifles. Our National Guard, which composed the bulk of our armed forces, had nothing better than single-shots of the type used by Custer to fight the Indians. Enough Krag-Jorgensons were found to supply the Rough Riders, but the other volunteers had to be content with 45-70’s and black powder. Everything considered, we came out better than we had any right to expect.

Horse-mounted cavalry figured in none of the battles, the Regulars and Rough Riders marching and fighting on foot the same as the infantry. Hence, revolvers were not used to any extent, and the only Smith & Wessons which played a part in the hostilities were the single-action .44’s purchased years before and carried by the Spanish officers. Hardly a case of revolver ammunition was expended in the Cuban campaign, outside of target practice.

Between the capture of the Buena Ventura and the signing of the armistice, somebody in authority in Washington gave Smith & Wesson an order for some revolvers. It totaled a picayune 3,000 guns, 2,000 for the Navy and 1,000 for the Army, and the manufacturers must have hoped that it would lead to something better or they would not have tooled up the machinery to produce it.

But the war with Spain simmered down to the diplomatic stage soon after the fall of Santiago—before Smith & Wesson had delivered a single revolver on the war order. Instead of cancelling its contract as it did at the conclusion of World War I, the U.S. government merely passed along the word that there was no particular hurry about delivery. This apparently satisfied Mr. Wesson, who had in mind an improvement on the design and obtained a patent on it October 4, 1898.

The contract tendered to Smith & Wesson was precise in some particulars. A hand-ejector was specified and the arm had to be chambered for the .38 Long Colt ammunition, on which the Government had been thoroughly sold before the war began. As a final indignity to the firm which had pioneered both the metallic cartridge and the automatic ejector, the contract called for left-hand-twist rifling, which S&W had not used except in its first venture in the revolver line—the little No. 1 .22.

But if some of the contract’s provisions were too inflexible to suit the manufacturers, others were left to the imagination. Principal among these was the diameter of the bore, and Mr. Wesson, having abandoned base-expanding bullets years before, saw no reason why the bullets should not be given a snug fit. Consequently, he reduced the bore to a small limit of .356 and a large limit of .357, dimensions which have been adhered to in all descendants of that First Model side-swing hand-ejector up to and including the Magnum.

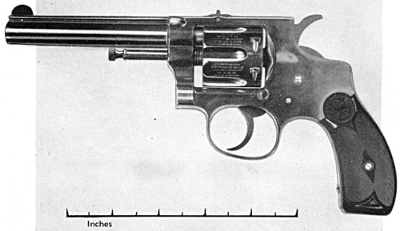

The First Model “Military & Police” .38 resembled the regulation Colt hand-ejector in outline, but the side swing yoke lock released by a forward pressure on the stud instead of a backward push. It had a rounded butt embellished with monogramless walnut grips and a 6 1/2-inch barrel (as supplied to the Government.) The same model with 4-inch barrel and hard-rubber grips was produced for the trade and police officers who knew their guns snapped them up eagerly. Although it was the first six-shot .38 made by S&W, the counter-clockwise rotation of the cylinder then adopted is still defended in the catalogues as permitting the side plate to be located on the right side where it will not be interfered with by the locking bolt and thumb piece. There are no records to show how many police revolvers were made in that First Model, but including the Government order, the serials run from 1 to 20,975.

First deliveries to the Government were made in March of 1899, but it is doubtful whether any of the weapons got to the Philippines in time to see service in the war proper. The insurrection itself dragged out a considerable distance beyond the formal close of hostilities, and in these engagements with supposedly untrained and undisciplined natives, the Smith & Wessons were as ineffectual as the Colts.

This was due to no defect in either hand gun but to the simple fact that the .38 Long Colt cartridge was not a man-stopper—however accurate it may have been for target purposes. Military authorities of that day were entirely to blame for not having tested the killing power of the missile on something larger than a jackrabbit.

The Tagals, the Igorotes and some of the lesser tribes involved in the fighting turned out to be much tougher opponents than the Spaniards; but the U.S. soldiers did not suffer any serious setbacks until they came to grips with the Moros.

As you may recall, these chaps were of Malayan extraction and Mohammedan in religion. Their knowledge of firearms was limited, but they had all taken post-graduate courses in the use of a long, shafted piece of cutlery known as the kris. It was modeled on the deck plan of a snake in motion and was adapted either to throwing or jabbing. Under extreme provocation, however, they discarded their krises and depended solely on a cleaver-like chopper called a bolo.

The Moros were practically indifferent to the battle risks which the average soldier is taught to avoid whenever possible. In common with all Mohammedans, they believed that the shortest course to the arms of Mohammed was to expire on the battlefield, and even greater glory awaited those who could take one or two “infidels” along with them on the last journey.

Such opponents were not easily discouraged. A bullet from the old-fashioned Springfields carried by some of the volunteers, or from a Krag if properly placed, or even a well directed bayonet thrust would stop a Moro; but the pellet from a .38 Long Colt had little immediate effect unless it lodged in the heart or brain. Many American soldiers made this discovery when they came in contact with the juramentados, but it was too late then for them to profit by their experience.

When the casualty rolls from this cause began to run high, somebody in the War Department remembered that several thousand retired Colt .45’s were packed away in heavy grease, ready to be sold to second-hand dealers. The big Colts were promptly resurrected and sent across the Pacific as fast as steam could carry them. Having arrived upon the scene, they not only assisted numbers of Moros to join the select company of Mohammed, but so reduced the religious fervor of others that they abandoned the campaign and went back to their mountain homes.

Failure of the .38 Long Colt cartridge in the Philippines led Daniel B. Wesson to design a better one, and the result was the .38 Smith & Wesson Special. It had a powder weight of 21 grains compared with 18 in the regulation cartridge, and the bullet gained 8 grains for a total of 158 simply by filling in the hollow base. The new cartridge was more accurate for target work than the .38 Long Colt and was heavy enough for ordinary police work, but the War Department had learned its lesson and refused to issue hand guns to soldiers of less than .45 caliber. An added refinement to the cartridge was contributed by the Colt company in the form of a blunt-nosed bullet of equal weight. It was known as the .38 Colt Special and experience proved it to be a better man-stopper than the S&W Special while sacrificing no accuracy for the change in shape.

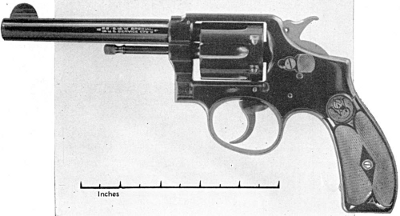

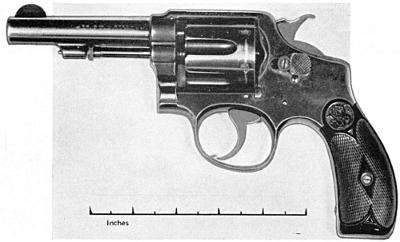

Smith & Wesson made no changes in the hand-ejector revolver chambering the new cartridge until 1902. Then a new model appeared under patent of December 17, 1901, with an improved method for holding the cylinder in alignment with the bore. This was accomplished by a forward cylinder pin lock, made by placing a round lug on the lower side of the barrel, through which operated a spring-actuated pin. The forward lock was in addition to the usual rear lock and supplied a more rigid brace for the cylinder. Perhaps pride has dissuaded the Colt Corporation from adding the forward cylinder lock to their hand-ejector revolvers. At any rate they have never done so, although the patent has expired long since.

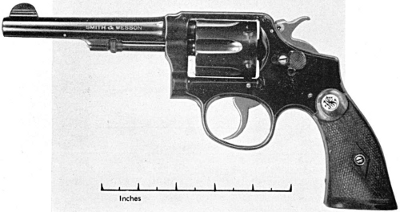

Serial numbers of the first type of the 1902 model revolvers run from 20,976 to 33,803. On October 27, 1903, several minor changes were made in the model, and on November 18, 1904, revolvers with square butts were put on the market. The second type begins with serial No. 33,804 and runs to 62,449, the square-butt type beginning about 58,000. Both checked wood and rubber grips were supplied on the round-butt revolvers, but those with square butts were made only with checked wood.