The following information on the Smith & Wesson New Century .44 Special Triple Lock comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

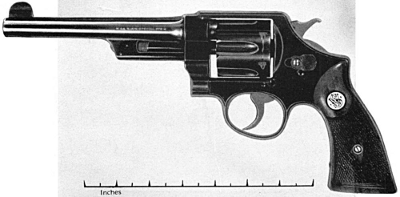

After 52 years of distinguished service in the firearms business, Daniel B. Wesson passed away in 1906, and in the following September the New Century .44 was announced. It was the first large caliber hand gun designed by the firm in many years and followed in general lines the square butt hand-ejector .38 Military and Police 1906 Model. A casing was designed to cover the forward cylinder yoke lock and extractor rod to withstand the heavier breech pressures to which it was subjected.

Although the .44 Russian cartridge had established a fine record for accuracy, it was generally believed that the powder charge was inadequate, so it was stepped up from 23 to 26 grains of black powder—all that was available at the time.

The case had to be lengthened to contain the heavier charge, but the weight of the bullet remained at 246 grains. With the development of smokeless powder, the velocity of the .44 S&W Special, as the cartridge was christened, has been increased to 780 f.s. and the muzzle energy to 330 foot pounds. Elmer Keith, who has taken some extreme chances with his reloading experiments, has boosted the velocity of this cartridge to 1,110 f.s. and claims that it is the hardest hitting hand gun cartridge made.

Besides 13,753 of the New Century, or Triple Lock Model made in .44 caliber, 1,226 were made for the .450 Eley cartridge and 21 for the Colt .45. Five thousand were made for the .450 Mark II British Service cartridge during the First World War.

The New Century barrel was made in lengths of 4, 5, 6 1/2 and 7 1/2 inches, with a weight of 39 ounces for the 6 1/2-inch barrel. It was furnished both in blued and nickeled finish and was one of the handsomest revolvers ever put out by any firm. But it had its drawbacks. The knuckle above the grips at the back of the frame formed a sharp corner and the frame itself was narrower than need be for such a large weapon. Along with its ballistic excellences, the cartridge caused a fairly violent recoil which jammed the knuckle of the gun into the web between thumb and forefinger. In spite of these disadvantages, many good pistol shots adopted the gun because of its accuracy.

Beginning with serial No. 15,525, the casing around the front end of the extractor rod was eliminated. This was about the time the United States entered the First World War and experience had shown that the casing was prone to become caked with mud under battle conditions and hence hard to operate.

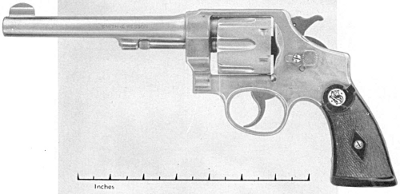

A heat-treated alloy steel cylinder like that used on the .38 Special was added to the gun beginning with serial No. 16,600, and in addition to the models made for the .44 cartridge, 727 were made for the .45 Colt cartridge. It is still being made, but only in 6 1/2 barrel length. In this second model, the back of the frame was given more curve along the grip, but nothing was done to eliminate the hand-splitting feature until 1938. Then the grip was extended to the corner of the knuckle, after the pattern of the .357 Magnum, and now a man can fire one repeatedly without gritting his teeth.

The official hand gun of the United States Army at the time of entry into World War I was the Colt .45 automatic, but it became quickly apparent that this arm could not be produced fast enough to meet the demand. Decision was made by the Government to fill the deficiency with revolvers and both the Colt New Service and the Smith & Wesson .44 were approved. But in order to abate the confusion in cartridges, both were ordered to shoot the .45 government automatic ammunition.

This presented a mechanical difficulty because the automatic cartridge was rimless and the extractors on the Colt and S&W revolvers had nothing on which to get a grip. Someone in the Smith & Wesson factory solved the problem with a semi-circular, three-cartridge clip which functioned perfectly in both revolvers.

Except for the differences in caliber and chambering, the 1917 model .45 turned out by Smith & Wesson was identical with the second model .44 hand-ejector. A butt swivel was added and the barrel was standardized at 5 1/2 inches, while the finish was modified from the customary blue-black to a lighter blue which did not require such lengthy processing. Eliminated as an unnecessary refinement in a service revolver was the checking on the walnut stocks, which did not appear again until the post-war models were in production.

Specifications for the Smith & Wesson Army Model 1917 provided for chambering and bore diameter but were silent as to the pitch of the rifling. After considerable experimenting, a ratio of one turn to 14.569 inches was adopted in preference to the Colt’s twist of one to 16 inches. Both manufacturers adhered to their respective traditions in the direction of rifling, Colt using the left-hand twist and Smith & Wesson the right. The latter company claims that its revolver showed greater velocity, penetration and accuracy than any other hand gun tested by the government.

A total of 175,000 of these military revolvers were delivered by Smith & Wesson to the United States government. The contract, therefore, was still short of the Russian quota by 25,000, but it is well to remember that the firm was occupied for six years in filling that order for the Czar, whereas the first deliveries of the World War Model were not made until October 9, 1917, just 13 months before the end of the war.

It is, of course, impossible to say how many of these revolvers saw active service in World War I, but undoubtedly they were faithful servants of many officers and men. Hand guns were rarely mentioned in news reports from the front, one of the outstanding exceptions being Sergeant York’s spectacular roundup of a German machinegun detachment with the aid of a .45 Colt automatic. Many Smith & Wessons were used by the military police, who frequently committed the sacrilege of employing them as clubs. In spite of the fact that thousands were issued to men who knew absolutely nothing about the care of revolvers, a large proportion survived the war and subsequent occupation of Germany and came back to the U.S.A. in prime condition.

Smith & Wesson began production of the Army Model commercially soon after peace was declared. The inscription “United States Property” disappeared from the side of the frame and the metal parts once more were finished in the well-known blue-black of pre-war days. Several changes were made in the ammunition for the gun—mostly on the side of economy. The clips which held the cartridges in groups of three were the first to go, since they performed no function except in the extraction of a rimless cartridge. Besides adding a rim to the cartridge, the metal jacketing of the World War cartridge was abandoned in favor of time-honored lead. Metal jackets were costly and destructive, Mr. F. C. Ness of The American Rifleman estimating that the life of a hand gun using jacketed bullets was not more than 5,000 rounds. Comparatively unimportant with a Colt automatic, which could be taken apart with the fingers for insertion of a new barrel, this item was much more serious for the Smith & Wesson. Replacing a barrel in a revolver is a major operation and an expensive one.

First of the lead bullets for the auto-rim cartridges were of 230 grains, exactly the same as the weight of the jacketed pellet. The contour also remained the same. But by interior alteration the case was enlarged to hold a heavier powder charge and a bullet of 255 grains, making it the same as the Peacemaker Colt cartridge, whose ballistics it very nearly equals. The punch of the cartridge could be increased by rechambering the revolver and lengthening the cartridge case, as the cylinder is plenty strong. Further increase in the weapon’s shocking power could be supplied by a square-nosed bullet.

Final improvement to the 1917 Army Model was made in 1938, when the Magna stock was designed to lessen the chopping action of the gun at recoil and make it more comfortable for the shooter. Serial numbers of this model start with 1 and all above 175,000 indicate post-war manufacture.

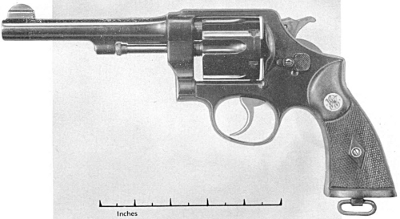

During World War I, Smith & Wesson also manufactured 73,650 revolvers for the British government, the arm being known as Model .455 Cal. Mark II. The first 5,000 were made by rechambering and reboring the New Century Model .44 and 525 of those bear the serial number of the New Century series. The encasing frame on the ejector was omitted after that and some minor changes were made in the structure of the frame. It was made in 6 1/2-inch barrel and in blued finish only. These guns chambered the British Caliber .455 Mark II cartridge or the practically identical Colt .455.

The British Model performed satisfactorily and was a great favorite with Canadian troops. It is not often seen today in this country, as it is no longer manufactured.