The following information on the Rollin White patent comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Competition developed for Smith & Wesson very early in the Civil War. Although they were turning out revolvers and cartridges at top speed, the orders must have come in virtually unsolicited, for they did not go to the expense of advertising them in the magazines of the day. Neither did they manufacture cartridges outside of the calibers suitable for their own arms, though if they had enlarged their plant to do so they could have realized a fortune.

Instead of making ammunition for the Spencer and Henry repeaters which were then coming into use, along with several varieties of single-shot metallic cartridge shoulder arms, they licensed other firms to produce such cartridges on a royalty basis. No doubt they felt that the complications and headaches attendant on making such a variety of cartridges sizes would more than overbalance the larger profits.

But Smith & Wesson’s coyness with regard to advertising was not shared by other manufacturers. As early as 1861, other firms were soliciting a slice of the revolver trade. Foremost among them was Merwin & Bray, of 245 Broadway, New York City, who advertised in Harper’s and Leslie’s Weekly “A NEW CARTRIDGE REVOLVER—carrying six bullets (80 to the pound).” Curiously, they did not specify the make of the revolver for which they claimed to be the agents, although the advertisement contained a column width illustration of the gun. The moderate price of $12 was asked for it.

Wording of the advertisement made identification difficult, but authorities are agreed that the revolver was the work of Daniel Moore of Brooklyn, N.Y. He obtained a patent on the gun on January 7, 1860, and it was a most ingenious weapon. Like all the percussion Colts except the side-hammer model, it had no top strap. Barrel and cylinder assembly pivoted at the front of the frame and upon pressure on a stud at the right the hammer, turned en masse to the right, permitting the ejection of empty shells and the insertion of fresh cartridges. A detachable rod under the barrel aided in extraction of the shells.

Besides the six-shot model described in the Merwin & Bray advertisement, Moore later made a heavier model, also of .32 caliber, chambered for seven cartridges, and a still larger model chambering .38 cartridges. These arms are especially interesting because they represent the first stage in the development of the side-swing, split-frame Colts and Smith & Wessons brought out years later and still use in their latest model revolvers.

The connection between Daniel Moore and Merwin & Bray apparently terminated early in January, 1862, because their advertisement of his revolver is omitted from Harper’s Weekly of the 11th and in the following issue is replaced by the following:

“PRESCOTT’S CARTRIDGE REVOLVERS

“The 8-in. or Navy size, carries a ball weighing 38 to the lb., and the No. .32 or 4-in. Revolver, a ball 80 to the lb. By recent experiments made in the army, these Revolvers were pronounced the best and most effective in use. For particulars call or send for a circular to Merwin & Bray, No. 245 Broadway, N.Y.”

Illustrations of both models and of their ammunition appear in the advertisement. Those of the cartridges are full size and the larger one, “weighing 38 to the pound,” is the .38 rim fire which was manufactured by cartridge companies as late as 1915. The diameter of the bullet is substantially the same as that of the .36 Navy Colt percussion ammunition and the portion which sets inside the cartridge forms a “heel” of slightly smaller diameter. The smaller revolver was chambered for the .32 long rim fire used in the Smith & Wesson revolvers of that period.

Produced by E. A. Prescott of Worcester, Mass., the revolvers themselves were strongly built, single-action affairs with solid brass frames and steel barrels. Axis rods which could be removed by pressure on a spring held the cylinders in place, while the cartridges were loaded into the chambers along a groove and through a slot in the recoil shield—same as the Harrington & Richardson bulldog models of today. To extract the fired cartridges you used a nail, pencil or any other probe you could find.

Magazine ads of the Civil War period ordinarily have to be regarded with skepticism, but the statement that the revolvers were the best and most effective weapons (of their class) in use, was perfectly true. The .38 Prescott six-gun was a real man’s weapon. In spite of the shoulder on the bullet to make it fit evenly in the case, it packed a very respectable wallop and was waterproof. Given decent treatment there was nothing about the weapon to get out of order—provided the powder fouling was removed frequently—and its good balance and long barrel made it effective on targets the size of a man at considerable ranges. Smith & Wesson must have been alarmed when they heard about the Prescott revolver, for structurally and ballistically it was vastly superior to their own products.

But the Prescott and Moore revolvers were not all of Smith & Wesson’s troubles by any means. At least a half-dozen firms were turning out cartridge revolvers, several of which were mechanically as good, if not better, than their own tip-up guns. This tip-up system, while popular, was one of the features which stood in the way of their making larger calibered revolvers. The latch arrangement by which the barrel was held to the bottom of the frame was none too strong, and the .32 cartridge was about the peak load that could be imposed on it.

One of the firm’s competitors had his plant located right in Springfield. The proprietor was James Warner, who formerly had been connected with the United States Armory in that city. He entered the revolver field as soon as the Colt patents expired with several percussion models, mostly of small caliber. But soon he was making cartridge revolvers, still adhering to the .28 caliber (going by the name of .30 caliber) which had distinguished his cap-and-ball arms. These cartridge revolvers were identical with his percussion models, solid frame, with only a cartridge-chambered cylinder and a loading gate added. They were put together well enough but were clumsy and unsightly, somewhat resembling the Wesson & Leavitt revolvers in outline.

A veritable hotbed of competition was Worcester, not such a great distance from Springfield. Not only was Prescott building there, but Allen & Wheelock, the firm that had employed both Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson, began to manufacture cartridge revolvers. So did Loren W. Pond and a member of the historic Lowell family—which is credited in that famous four-line poem on Boston as addressing only the Deity.

Allen & Wheelock’s revolvers were based upon a couple of patents of the senior member of the firm, a prolific inventor. Taken out in 1858, these inventions had to do with the cylinder pin and a side-hammer mechanism somewhat resembling that of Colt’s first solid-frame arm of 1855. The A&W cartridge revolvers also were of solid frame, substantially made, with “a dependable rotating system which brought the chambers into exact alignment with the barrel.” The cylinder stop was operated by connection with the trigger and lay exposed to the vulgar gaze on the outside of the lower strap.

The patented cylinder pin resembled nothing more than a modern wire nail with a segment ground from the upper side of the head where it rested against the barrel, to keep it from falling out. Extending clear through and out at the back of the frame, possible only on a side-hammer model, the pin was prevented so effectually from falling out that its removal was always difficult and sometimes impossible without a full kit of tools. Cartridges could not be inserted through a slot or loading gate without the side-hammer being cocked; consequently no gate or slot was provided. This feature did not add to the satisfaction of an owner who had to pause in the heat of battle to drive out the axis pin for the purpose of re-loading his weapon. The side-hammer model was available in a seven-shot .22 and a six-shot .32 long rim fire.

Later, the Allen & Wheelock center-hammer .44 percussion revolver was adapted to shoot the Henry rim fire cartridge, but whether this was during the Civil War or after 1869 (a significant date which will be referred to later) is not known. This big gun had a lot of surplus metal in the frame and its loading rammer was operated by a movable trigger guard which served as an extractor for the metallic ammunition.

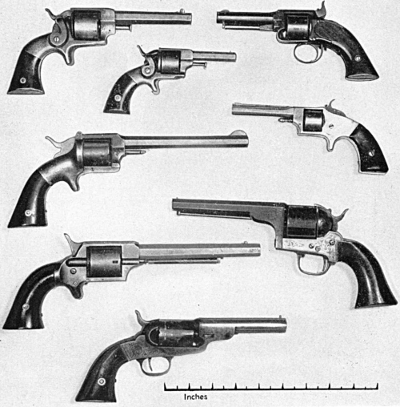

Warner .30 Rim Fire Revolver. Infringement of Rollin White patent.

Allen & Wheelock .22 short Rim Fire Revolver. Infringement of Rollin White patent.

Lowell .22 Rim Fire Revolver, marked “Rollin White Arms Co.” held to be an infringement of Rollin White’s patent.

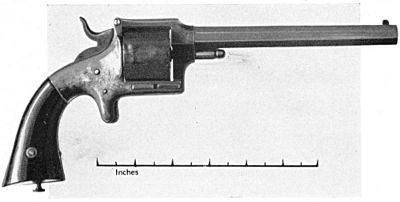

Pond .32 Long Rim Fire Revolver. Infringement of Rollin White patent. Also made in .44 caliber (see Plate 10).

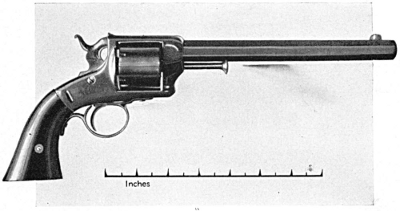

Moore .32 long Rim Fire Seven Shot Revolver. Blued barrel, bronze, silver plated engraved receiver.

Cone .32 long Rim Fire Revolver, made by J. P. Lower. Revolvers of identical construction are said to have been made in Charleston, S.C. during the Civil War.

Bacon .31 Percussion Revolver, converted to shoot .32 short rim fire cartridge by some unknown gunsmith who counterbored the back of each chamber of the cylinder, so as to encase the heads of the cartridges.

Another strong competitor of Smith & Wesson was Loren W. Pond, who obtained a patent on July 10, 1860, and began to manufacture a type of revolver which in several respects was superior to the S&W. Like the latter, it used the tip-up system for loading and extracting but it was not hinged at the forward end of the upper frame strap. Instead, the joint occurred immediately in front of the hammer, as had the revolvers of the Massachusetts Arms Company almost 10 years before. The cylinder was attached firmly to the barrel base by a cylinder pin and swung upward by action of a latch operated by a release lever on the left side of the lower strap. In an exposed position on the lower strap was the cylinder stop.

More of a target arm than any of the early pistols, the Pond revolver had a rear sight formed by a notch in the center of the barrel hinge which gave a good view of the front sight. Its oversize hammer looked clumsy, but actually it was very handy for quick cocking. Illustrated is the .32 revolver which went to war with Lieut. Albert Dowd of the 18th Massachusetts Volunteers. The bore has sustained considerable wear and tear, but it beat a Smith & Wesson Model 1 1/2 at 20 yards by a wide margin. Since both weapons were shot by the same man, superior aiming ability did not enter into the contest. But Pond, like Smith & Wesson, neglected to provide a safety notch for the hammer.

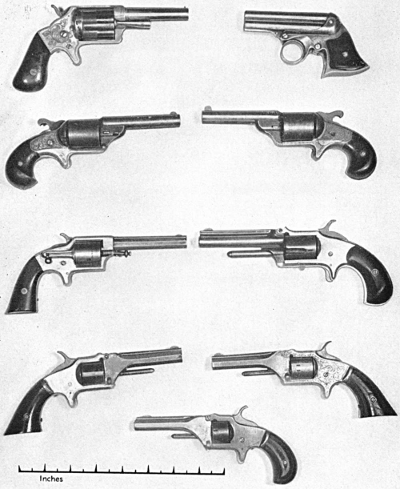

Remington cartridge, four-shot pepper box pistol. Elliott patent.

National Moore .32 ‘teat’ cartridge revolver, loading from front of cylinder. An evasion of Rollin White patent. Illustration shows both sides of this gun.

Plant .32 ‘teat’ cartridge revolver, loading from front of cylinder, another evasion of the Rollin White patent.

Deringer .32 rim fire revolver, manufactured 1874 after expiration of Rollin White patent.

American Standard Tool Company .22 long rim fire revolver, plain model, very similar in appearance to the Second Model Smith & Wesson .22, but has cylinder stop below the cylinder. Manufactured after expiration of Rollin White patent.

American Standard Tool Company Revolver, engraved model.

Ailing Revolver, similar to American Standard Tool Company Revolver, .22 short round butt, manufactured after expiration of Rollin White patent.

Most of the revolvers Pond manufactured were chambered for the .32 long rim fire, but shortly before the inventor was caught in the legal cyclone soon to be described he produced a few of .44 caliber. Its comparatively rugged construction enabled it to withstand the impact of the larger cartridge without endangering the latch.

Had any of the firms which manufactured .44 caliber cartridge revolvers during the Civil War been able to produce them in quantities sufficient to equip the Federal cavalry, that branch of the service would have possessed an arm vastly superior to the cap-and-ball weapon on which they were obliged to depend. But even adequacy of production might not have guaranteed for the horse troops he-man revolvers shooting waterproof ammunition. The brass-hats of the ordnance board would still have had to be won over to the new arm, and judging from their frequent and vigorous disapproval of the Spencer and Henry repeating rifles, this would have been difficult.

Just getting into operation when the Smith & Wesson patent litigation started was the Lowell revolver plant. It produced a sturdy gun similar in construction to the solid-frame Prescott revolver, and as far as can be learned was made only in .32 caliber.

Lastly, under the head of competitors, may be mentioned the Elliot, Sharps and Rupertus cartridge pepperboxes, although they cannot properly be classified as revolvers because the nest of barrels in each case remained stationary while the firing pin rotated. Elliot’s pepperbox was much advertised in the magazines early in the War and could be purchased in a blued finish for only $9. The nickel-plated model cost an additional dollar. Emphasized in the advertisements is the fact that it had “gain twist” rifling, then supposed to possess some extraordinary merit, but the ad writer was careful not to mention that the arm chambered the .22 short (later it was available in .32 caliber). The fantastic claim that its bullet will penetrate an inch of pine at 150 yards is on a par with the miraculous cures alleged for the patent medicines of the same period, which were said to work on bunions and boils with equal efficacy.

This competition must have irritated the partners at Smith & Wesson no end. If the competing arms had been obviously inferior, the hurt might not have rankled, but the fact was that several were better than the best that S&W had been able to produce.

Undoubtedly Daniel B. Wesson recalled that he had once been on the receiving end of a patent suit, and one day in the early fall of 1862 he boarded a train for New York with blood in his eye. He visited a number of New York firearms dealers, making purchases which he stowed away in his carpet bag; then he crossed on the North River ferry and took the train for Washington and a conference with his patent attorneys—the same with which his firm previously had done business.

In the course of the conference, the various revolvers he had bought were displayed and torn down, while the attorneys prepared notes and studied the patent records. When the job was completed, the senior solicitor addressed Mr. Wesson along the following lines:

“I cannot see, sir, why your firm should not be successful in suits against all these arms manufacturers. Every one of them has produced and marketed revolvers in which the cylinders are bored clear through, in direct infringement of the Rollin White patent. You are sole owner of that patent by assignment, and it still has some years to run. I would recommend that you take action at once.”

“I guess what you say is true,” Mr. Wesson responded, “though I kind of hate to go after some of those fellows. My partner and I worked for years for Allen & Wheelock and I’ve known Prescott for a long while, too. Suppose you write letters to those two and see first if they won’t stop making their revolvers of their own accord. If they won’t, we’ll sue them along with the rest.”

The patent attorney’s arguments in their letters to Allen & Wheelock and E. A. Prescott must have been persuasive, because both firms heeded the warnings promptly. Allen & Wheelock abandoned the manufacture of cartridge revolvers and put their employees to work on war contracts, of which they had plenty. Prescott had a long session with his own attorneys and then directed Merwin & Bray to discontinue the advertising in Harper’s and Leslie’s Weeklies because they could no longer fill orders for their solid-frame weapons. Both firms may have been incensed at the S&W partnership, but after watching the infringement proceedings they probably concluded that they had been favored after all.

Within a few days, Daniel Moore, James Warner, Lowell and L. W. Pond were served with process in infringement suits, along with which came injunctions prohibiting them from manufacturing cartridge revolvers pending outcome of the action, and they closed their plants abruptly.

How these firms’ own patent attorneys had overlooked the Rollin White patent is a matter upon which we can only speculate today. Presumably their search had stopped with the Smith & Wesson patents, in which the bored-through cylinder was not claimed as a novelty, and they had assumed that it was not a patentable feature. In any event they had not come across the Rollin White assignment. They made a vigorous fight in their clients’ defense, but it was too late then.

By consent, the suits were consolidated in the Federal court in the District of Massachusetts, and after a trial which lasted several days the judge ruled them guilty of infringement of the Rollin White patent and assessed heavy damages. Probably the most humiliating part of the judgment was a provision that the defendants must turn over all unsold revolvers to the plaintiffs. Thereafter, all revolvers they manufactured were die-stamped below their own inscription: “Manufactured For Smith & Wesson.”

As the spoils of victory, the partners at S&W received 1,513 revolvers from Warner, 4,486 from Pond, 3,376 from Moore and 8,682 from Lowell. Special leniency must have been granted in Lowell’s case, because the turnover was not completed until 12 years later, in 1875.

The decision left Smith & Wesson sitting on top of the cartridge revolver world—or at least the western hemisphere. Except for those licensed to manufacture for Smith & Wesson, the only firms left in business were producers of small cartridge pepperboxes, who had never ranked as serious competitors.

Most remarkable of all the aftermaths of the legal victory was the fact that the winners did not immediately invade the field of large calibers. Their own tip-up models were not sturdy enough to take the shock of the .44 cartridges on account of the weak barrel lock, but they could easily have made solid frame revolvers without trespassing on anybody’s patent rights. Nevertheless, the records show that they clung steadily to their old models until 1869, when the war was over, save for disposing of larger guns turned over to them by their defeated competitors.

A prime reason for this probably was that their facilities were taxed to the utmost as it was and they were making all the guns and all the money possible without tooling up for a new model. Their revolvers speedily became popular as police weapons, and many of them took their toll in the New York riots. Members of the Secret Service used them almost exclusively because of their small proportions, ease in loading, and waterproof ammunition.

The expedients resorted to by manufacturers to evade the patents ran the gamut from the ingenious to the ridiculous. Under a patent granted to an inventor named Slocum, the defeated Moore made revolvers in which the cylinder was a mere cage into which were fitted removable chambers. But a revolver which had to be loaded twice was at a hopeless disadvantage from the beginning, so that venture failed.

Nothing daunted, this same Daniel Moore developed another type of revolver in which the chambers were closed at the rear save for a tiny opening made to accept the tip of the hammer. The cartridges were quite unlike the rim fires, being rounded at the base so that they could be inserted in the chambers from the front. A small protuberance in the center of the cartridge base contained the fulminate, and of course this little pimple projected into the aperture which had been left in the back of each cylinder. The cartridge case enclosed the bullet as well as the powder charge and was flanged at the front to hold it in position in the chamber. For obvious reasons, this type of cartridge ammunition immediately earned the vulgar name of “teat” cartridge.

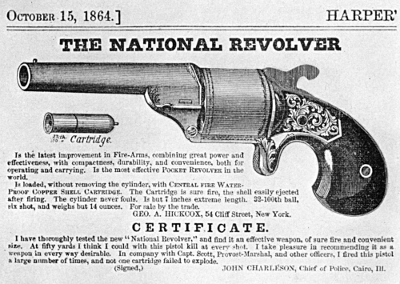

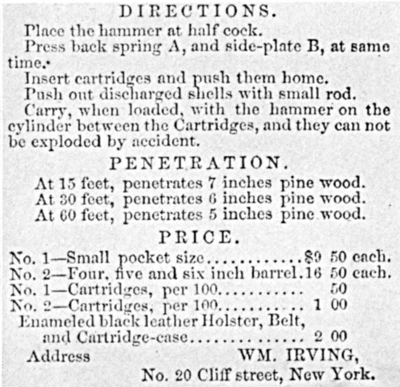

The weapon which used this ammunition was known as the “National Revolver” and it was well advertised when it went on the market in 1864. Unprepossessing in appearance, with an ugly grip which would accommodate but two fingers of a normal hand, it boasted rifling and internal mechanism as fine as the best. However, it was prone to get out of order because of its numerous and delicate parts.

An advertisement of this gun carried in the Harper’s Weekly of October 15, 1864, is interesting not only because of the descriptive material but also because it introduces us to a now forgotten character in handgun history—the redoubtable John Charleson, chief of police of Cairo, Illinois:

“THE NATIONAL REVOLVER

Is the latest improvement in Fire-Arms, combining great power and effectiveness, with compactness, durability and convenience, both for operating and carrying. It is the most effective POCKET REVOLVER in the world. Is loaded, without removing the cylinder, with CENTRAL FIRE WATERPROOF COPPER SHELL CARTRIDGE. The Cartridge is sure fire, the shell easily ejected after firing. The cylinder never fouls. Is but 7 inches extreme length. 32-100th ball, six shot, and weighs but 14 ounces. For sale by the trade.

“GEO. A. HICKCOX, 54 Cliff street, N. Y.”

“CERTIFICATE

“I have thoroughly tested the new ‘National Revolver’ and find it an effective weapon, of sure fire and convenient size. At fifty yards I think I could with this pistol kill at every shot. I take pleasure in recommending it as a weapon in every way desirable. In company with Capt. Scott, Provost-Marshal, I fired this pistol a large number of times, and not one cartridge failed to explode.

“(Signed) JOHN CHARLESON, Chief of Police. Cairo, Ill.”

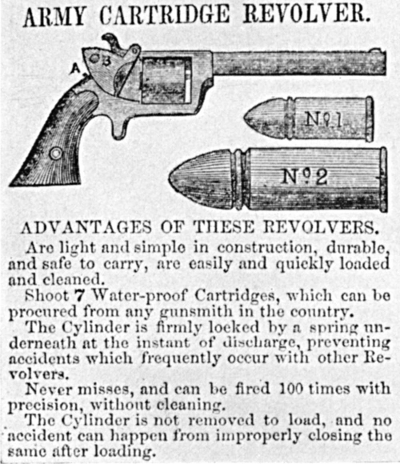

Daniel Moore wasn’t the only manufacturer of teat cartridge revolvers. Merwin & Bray sponsored two very similar models shooting the same ammunition and known as the Eagle and Plant revolvers. Contours are not patentable and both these guns resembled the Smith & Wesson in outline, although they were of solid frame construction. A manually operated gadget which was neater than it sounds was placed at the rear of the cylinder for expelling the spent cartridges.

The teat cartridge and the weapon which fired it were the most ingenious and successful of all the inventions aimed at evasion of the Rollin White patent, but they did not constitute a real challenge to the Smith & Wesson. Advertised statements to the contrary notwithstanding, the cylinders of the Moore, Eagle and Plant revolvers did foul up as often as those of other brands. Quite a lot of pressure was required to force the cartridges into fouled cylinders, and soon newspaper items began to appear concerning citizens who had lost fingers, hands or eyes while loading their revolvers. Frequently the blame was laid on teat cartridges, and the public became prejudiced against them. The plant at Norwich, Conn., which had produced the Eagle and Plant arms, gave up the ghost; but nothing was able to stop Daniel Moore for long. He went into a protracted session with his drafting board and designed the most hideous single-shot derringer that any American manufacturer had produced up to that time. He seemed to run to the grotesque in firearms. Somehow he interested the Colt people in his latest monstrosity and sold the gun to them.

No discussion of front-loading cartridge revolvers would be complete without mention of all ill-fated experiment of the Colt Patent Firearms Company in the late sixties. Their patent attorneys wisely had advised them to stay out of the rim fire revolver game as long as the Rollin White patent was in force, but when a man named Theur came along with a new type of ammunition he had patented, they sat up and took notice.

Theur’s invention—much like the teat cartridges already mentioned—consisted of a rimless, center-fire cartridge which could be inserted at the front of the revolver chamber instead of at the rear, thus avoiding infringement of the patent on bored-through cylinders. Some authorities insist that the Colt firm never offered revolvers using the Theur cartridge on a commercial basis, but some collectors have specimens of the weapon put up in handsome cases and with a box of cartridges thrown in.

The most interesting feature of this gun is its ingenious but highly complicated extractor. A one-sixth turn in the recoil shield behind the cylinder brought into alignment a pin which acted obliquely, striking the base of the cartridge next to that opposite the bore. Impact of the hammer on this pin threw the expended cartridge forward out of the cylinder.