The following information on the Smith & Wesson .38 Special comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Some of us, during the first World War, became personally acquainted with the British military revolver, the Webley .455 official nomenclature, Pistol No. 1, Mark VI. It was a sturdy piece, built on the top break system, with an extra locking feature something like that of the Schofield Smith & Wesson, but double-action, of course.

The British have always had odd ideas about revolver loads. Their first military cartridge revolver, the Enfield .476, used a 265 grain bullet backed by an 18 grain black powder charge, which trundled it out of the barrel at the rate of some 600 feet per second, with a trajectory like a trench mortar. It was not strange that some of the officers for whom it was regulation, substituted double-barreled pistols with pumpkin sized ball, when they were sent to fight the Afghans and the Fuzzy-Wuzzies.

The ballistics of the Mark VI were not much different from those of the Enfield .476, although it fired a 7 grain cordite charge instead of the 18 grain black powder one, which at least did not smudge up uniforms so badly. The gun itself was handy and well balanced and shot accurately and fast.

The Mark VI continued to be regulation for some years after the Armistice, but about 1928, the British Ordnance Office began to consider the adoption of a smaller calibered revolver, and in 1938, Pistol No. 2, caliber .380 was issued in its place.

So far as externals are concerned, the .380 Enfield bears a strong resemblance to the .455 Webley, in slightly reduced dimensions. It weighs twenty-eight ounces, against the forty of the Webley. The British experts had busied themselves with the lock work and other operating parts, speeding up the action considerably. The barrel was cut down from six to five inches, making it handier to point.

It was not necessary to design a cartridge to fit the .380, as the .38 W&S (Webley & Scott) fitted the specification of a heavy bullet combined with a small powder charge and low velocity. This cartridge was nothing more nor less than the S&W Super Police, which had been developed in this country for the purpose of thinning out the gangster population.

As to the efficacy of the Super Police cartridge, we might cite the instance mentioned by Colonel Hatcher in his “Textbook of Pistols and Revolvers” of the East St. Louis policeman who tried it out at 75 yards on a fleeing hold-up artist. The coroner reported that he found the bullet halfway through the subject and flattened to the size of a quarter.

To get down to figures, the .38 Super Police is loaded with a 200 grain bullet, long and flattened at the point, impelled by a relatively low powder charge at a velocity of 630 f.s. and has a muzzle energy of 166 foot pounds:

If the Ordnance Board experts had not been in such a hurry, they might have read further in the cartridge catalog and found that there was another .38 cartridge which would have fitted their purposes still better, the big brother of the one they selected, known as the .38 Special Super Police. Its bullet was of the same weight and proportions as the one already described, but having a larger powder charge it left the revolver muzzle at the rate of 745 f.s. developing a striking powder of 246 foot pounds. However, they seemed entirely satisfied with the ballistic co-efficients of the lighter cartridge and took it over intact, as the standard British .380 Service cartridge.

Up to the time of the Dunkirk disaster, in World War II, hand guns had not been issued to the rank and file of the British army. Something happened then, it might have been the feeling among the British people that they were fighting with their backs to the wall, that moved the War Office to make a radical change in arming its soldiers, not only the commandos, who were a law unto themselves, so far as weapons were concerned, but the British, Canadian and Australian line troops as well, with revolvers.

It was a weird course of revolver practice that was prescribed by the regulations. They might have been written by Wyatt Earp or Bill Hickok with Ed McGivern collaborating. There is no slow fire, single action, in the curriculum. Indeed, the .38-200 cartridges were not adapted to that sort of shooting. At a range of anywhere from five to twenty yards, a man was taught to be able on the appearance of a concealed, man-sized target, to draw and slam six shots into it before it disappeared.

It was plain from the start that the facilities of the British arms factories were insufficient to meet the demands for the new revolvers and as had been done in World War No. 1, the deficiency had to be supplied in the United States, and bearing in mind the very material aid furnished in the past by Smith & Wesson, the War Office wasted no time in calling upon them with an order.

On account of the urgent need, there was no time for Smith & Wesson to design a new revolver and make and install the necessary machinery to produce it. The question considered was which of the firm’s existing models came the closest to meeting the British specifications with the least possible modification of plant equipment. The Regulation Police Model as it was would, of course, handle the .38-200 cartridge with perfect safety but it was a five instead of a six shooter and its weight (18 ounces) put it out of the running as a military arm.

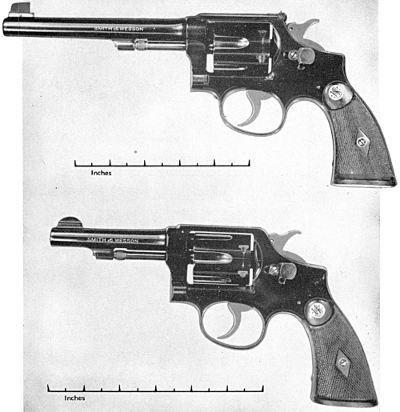

Above—”S&W Pistol No. 2″ British .380. Service cartridge, with 5-inch barrel.

Center—.38 Special with 4-inch barrel, U.S.

Below—Same, with 2-inch barrel.

It was but natural that the lot should fall upon the tried and true Military and Police model, designed to shoot the .38 Special cartridge. The job of adapting it to the shorter .38 Super Police cartridge was not as difficult as one might suppose. The bullet diameter is a hair’s breadth or so larger than that of the .38 Special, but not enough but what it could be fired through the barrel, with perfect safety. You reloaders know that such things can be done with slightly over-size bullets with entire impunity.

The chambering of the cylinders had to be enlarged, for the taper of the .38 cartridge is sharper than that of the Special, but this was a minor operation. There is an unrifled space of chamber through which the bullet has to pass before it strikes the barrel. That is nothing new. It existed in the 1917 Smith & Wesson and Colt Military revolvers and did not materially affect their accuracy. Like the British Enfield revolver, the “S&W Pistol No. 2” has a five inch barrel. It weighs about 30 ounces.

Being a military gun, it has the square butt and following the practice adopted in the First World War with the Model 1917 .45 revolver, the high gloss finish given to Smith & Wesson arms in times of peace, was omitted. The number of revolvers produced by Smith & Wesson for the British Government on this war order is at present a military secret.

Somewhat later, Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Mfg. Co. also took on a contract to make .38-200 revolvers for the British Government, which selected the Colt Official Police Revolver as the model to be adapted to military purposes. Built on the .41 frame and normally shooting the .38 Special cartridge, changing it over involved the same process applied to the Smith & Wesson Military and Police Model, but it is slightly heavier, weighing, with the five inch barrel, 32 ounces.

It remains to be seen if the British theory that a heavy bullet propelled by a relatively light powder charge is more effective than a medium weight bullet of the same diameter with a heavier charge and higher velocity is correct. It has a precedent in artillery practice in the carronades, short cannon of as high as eight inch caliber, firing solid shot at low velocities, which formed the bulk of British naval armaments during the Napoleonic wars. It was claimed that their shot had a greater shattering effect, within their limited range, than those fired from the long 32, 42 and 68 pounders with far heavier charges. Whether a .38, 200 gr. jacketed* bullet driven at the rate of 630 f.s. will inflict corresponding injury upon the human frame is a question that requires actual demonstration. Undoubtedly, by this time these revolvers and cartridges have been tried out a-plenty, under actual combat conditions, but so far the results have not been made public. [*Jacketed bullets are required by the Hague Convention.]

The Smith & Wesson Military and Police Model, with square butt and four inch barrel was turned out, chambered for its own proper cartridge, the .38 Special, for issue to our Coast Guard and to the Personnel of the U.S. Naval Flying Forces. This is known as the “Victory Model.”

Lastly, and maybe this is strictly confidential, the FBI sent in and obtained a good sized order of Military and Police Model Revolvers, with two inch barrel and square butt, chambered to take the .38 Special Cartridge, in the same rough finish previously described, presumably for use as a hide-away gun. This is also called the “Victory Model.”