The following information on Smith & Wesson Automatic Pistols comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

In dealing with the big hand-ejector models we have departed from the chronological order of our story and now must return to 1909 and the automatic ejectors.

The jointed frame, top-break system of simultaneous ejection had long since become common property by expiration of the King and Dodge patents and the old story of price competition was being told again. Firms manufacturing cheaper grades of revolvers were utilizing the system and customers who knew nothing about the differences in materials and workmanship involved could see no reason why they should pay substantially more just to get a hand gun bearing the S&W imprint.

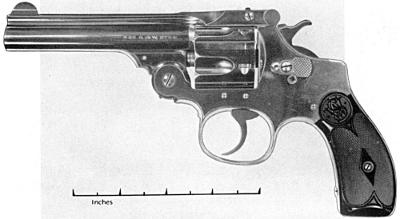

This probably was what induced Smith & Wesson to announce in the catalogue of January, 1909, their .38 caliber double-action “Perfected” revolver, even though they continued to make the Fifth Model double-action in the same caliber until 1911.

Like its predecessor, the Perfected Model was designed as a police and pocket arm. Its five chambers accommodated the .38 S&W cartridge, but it had a heavier frame than the Fifth Model and the trigger guard was an integral part of it. The lock work had been entirely remodeled, with spiral springs substituted for flat springs and a rebounding hammer guarded against accidental discharge. The ordinary locking device was provided on the top strap, but a push button was added on the side of the frame which had to be exercised before the top strap could be raised and the cartridges ejected.

This model was supplied in barrel lengths running from 3 1/2 to 6 inches, the latter being popular for light target work, and the finish was either blue or nickel. Grips were of hard rubber and rounded. A total of 58,398 copies of the Perfected Model were made and its manufacture overlapped that of the Regulation Police Model before it was discontinued in 1920.

Smith & Wesson had made no automatic pistols before 1913, although the Colt Corporation, the Savage Arms Company and other firms were selling them as fast as they could be produced. In that year, however, a deal was made with Charles P. Clement of Liege, Belgium, whereby Smith & Wesson was permitted to manufacture automatics bearing his patented features. Sale of these weapons was restricted to the United States under terms of the agreement, which paralleled the Colt Corporation’s acquisition of the Browning patents.

The Clement automatic had several novel and desirable features. A barrel made solid with the frame gave improved accuracy, while a bolt release catch on the left side of the frame made it possible to retract the breechblock and cock the pistol without having to overcome the tension of the return spring. The pistol could not be fired if the magazine were removed while a cartridge remained in the barrel. By pulling out on the trigger guard, the barrel-frame assembly was released in front and the barrel could be tilted for insertion of a cleaning rod from the breech. The barrel itself was 3 1/2 inches long.

On the right side of the grip, in front, was a safety catch which had to be pressed in order to fire the pistol. It was supplied only in blue-black finish with plain walnut grips, and the magazine accommodated seven of the original type cartridges.

As manufactured in Belgium, the Clement pistol was chambered for the 7.65 mm. cartridge, known in this country as the .32 Automatic Colt Pistol cartridge. It was a jacketed bullet and there was a traditional dislike in the Smith & Wesson organization for that kind of ammunition because of its punishing effect on the bore.

But cast bullets of sufficient hardness and polish to function perfectly in an automatic action could not be produced, so the firm’s ballistic experts went into a huddle to solve the problem. They finally produced what they termed a “half-mantle” cartridge with a cupro-nickel jacket covering its tip and most of its conoidal surface. The covering ceased at the point of the bullet’s largest diameter, so that the part which encountered the lands and grooves of the barrel was naked lead. If the designers had given equal attention to the case and powder charge, they would have done their firm a service, but the fact was that the cartridge had a velocity and energy considerably under the .32 automatic.

However, the “half-mantle” cartridge was duly patented and other cartridge manufacturers were obliged to pay for the privilege of making it—which didn’t assist its popularity. Someone at the Smith & Wesson plant was responsible for the misstatement that it was a “.35 Automatic Smith & Wesson Pistol Cartridge,” whereas the bullet diameter was actually .320, or just .008 of an inch larger than the .32 A.C.P. The latter cartridge could be fired with fair accuracy from the Clement-Smith & Wesson pistol, but the S&W cartridge stuck in the throat of the chamber of the .32 Colt automatic because of that extra .008 of an inch.

The “half mantle” would have had a big sale if Smith & Wesson had been content to let it stand upon its very obvious merits. The same principle could have been applied to bullets in other calibers of automatics and the firm would have made thousands in additional royalties. But they didn’t see it that way.

Other factors conspired to restrain the sale of the pistol and its excellent ammunition. The deceptive and inaccurate designation of the latter gave shooters the idea that the cartridge might be hard to obtain in out-of-the-way places, and actual tests showed that it was not the equal of the .32 automatic cartridge in speed and punch. Consequently, only 8,350 of the automatics were manufactured, regardless of the improved bullet which gave the barrel a life expectancy 20 times as long as the standard automatic.

Among those who appreciated the real worth of the Smith & Wesson automatic were members of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Many agents carried them during the First World War, and while it was rather small for serious work it delivered the goods in the hands of those skilled marksmen to their entire satisfaction.

Manufacture of the automatics was discontinued in January, 1921, but was resumed a few years later (the records are hazy as to dates). When it was returned to production it was chambered for the standard .32 automatic cartridge. Recent Smith & Wesson catalogues have omitted mention of the automatic, but it is still obtainable from some of the larger wholesale concerns.

To an outsider, the Smith & Wesson record on automatics seems unfortunate all the way around. It is regrettable that such a fine gun is no longer produced and even more of a pity that the half-mantle bullet has not been made for other and larger calibers of automatics. Such ammunition would place automatics on a par with revolvers in barrel longevity. It must be conceded, however, that not one pocket automatic in a thousand exhausts its barrel life unless the owner happens to be a gun crank.