The following information on Smith & Wesson Double Action revolvers comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Evolution of the revolver during the years just covered is remarkable for one manufacturing omission—the double-action principle. The system itself antedated the pepperboxes, for Ethan Allen made double-action, single-shot pistols under an earlier patent than Colonel Colt’s.

During the percussion period, Cooper revolvers were produced with double-action, as were the hammerless Pettingill which came out in 1856, the Starr and the Remington Rider. Many good Adams and Tranter double-actions came to this country from England during the Civil War, along with a number of French and Belgian trigger-cocking hand guns which couldn’t be used single-action. Colt did not produce a double-action hand gun for metallic cartridges until 1877, and Smith & Wesson lagged behind until February of 1880, when they brought out a double-action .38, shooting the cartridge previously designed for the single-action revolver.

It was very similar in outline to the single-action of the same caliber, but carried a bow-shaped trigger guard in place of the spur guard. The cylinder stop was of rocker type, requiring a double series of stop notches in the cylinder, with a free grove to accommodate its action. Half and full-cock notches permitted the hammer to be used single-action as well as double.

Design of the trigger was especially ingenious, with a flanged finger piece held in position by a V-shaped trigger spring operating on the rocker stop. The front sear was joined to the trigger and held in that position by the hand pivot, giving extra leverage for an easy pull when used double-action. Distinguishing the original from subsequent models is the side plate, in which the cuts run across the side of the frame, thus departing from the previous irregular shape.

As the new double-action would do everything the single-action would do, along with a few tricks of its own, it attained popularity from the start. Twenty-five thousand were built in that caliber with the above specifications. In September, 1880, a .32 double-action was offered shooting the same cartridge as the .32 single-action. It was a smaller replica of the .38 except for the irregularly-shaped side plate, which had been restored when it was found that the straight-line type weakened the frame.

This diminutive hand gun was also well received and was sold to 22,172 customers who wanted a revolver on the premises and weren’t particular about its lethal qualities.

Beginning with serial number 25,001 and continuing to 119,000, the Second Model double-action .38 was manufactured with no alteration except in the side-plate. This reverted to the irregular type which had served so well since the Second Model .22 was designed before the Civil War.

In the Third Model .38, the location of the latch notch of the rear sear was changed to give a lighter trigger pull when the weapon was used single-action. Although this required a corresponding change of the full-cock notch on the hammer, the two models are hard to identify except by reference to the serial numbers. Third Model serial numbers begin with 119,001 and run to 322,700.

In January of 1882 the Second Model .32 double-action was introduced with only one change. The rocker-type cylinder stop was eliminated and a long, slender, extended arm was substituted. Although this improvement did away with the extra set of notches, the cylinder stop remained partly exposed and a catch-all for dirt. Second Model serials run from 22,173 to 43,405.

The Third Model .32 d.a. differed only slightly from the Second, except that the side walls of the trigger were made to cover the rear sear and cylinder stop. These were made more compact so as to be fully encased in the trigger slot. Serial numbers run from 43,406 to 327,641 when it was discontinued in 1919 after the longest run of any Smith & Wesson model.

The Fourth Model .38 double-action appeared shortly after April 3, 1889, and did away with the rocker-type cylinder stop, along with the unsightly extra cuts in the periphery of the cylinder. The walls of the trigger were made to cover the rear sear and cylinder stop, as had been done previously in the .32 model. The cylinder stop also was made along lines similar to the .32. In this shape, the model ran from serial 322,701 to 539,300, when it was superseded by the Fifth Model, which differed from it only slightly.

In the Fifth Model, which ran only from 539,301 to 554,077, the front sight was forged solidly to the barrel and a square hole was broached to receive an improved barrel catch cam and coil spring. Although the Fifth Model was discontinued in 1911, its “soul went marching on” in the .38 “Perfected Model,” which overlapped it by a couple of years.

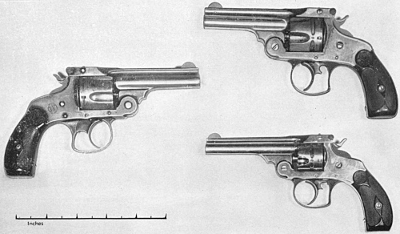

Smith & Wesson, Double Action .38 Revolver (Second Model) .38 S&W cartridge.

Smith & Wesson, Double Action .32 Revolver (First Model) .32 S&W cartridge.

From May, 1881, to some time in 1913, Smith & Wesson manufactured a big revolver known as the .44 Double Action. So great was its resemblance to the .38 that only close attention to details would distinguish them. In proportions and weight, it approached closely those of the later model .44 Russian single-action, although the frame was slightly shorter from the top latch to the butt, due to the shorter hammer throw.

The .44 d.a. used the Russian cartridge, but it was available on special order to shoot the .44-40 or the .38-40 Winchester rifle cartridge. The surface of the cylinder was disfigured, if you view it that way, with the same double series of stop notches and free grooves which appeared on the .38, except that there were more of them because it was a six-shooter instead of a five.

Nevertheless, it was a sturdy, dependable hand gun, with little about it to get out of order. It might have been an efficient auxiliary to the civilization of the West, except that the Colt was so popular out there that no other revolver could get a toe-hold.

But the .44 double-action was esteemed highly as a naval revolver by several foreign nations, including some in South America, even though it didn’t set the west on fire. It received none of the honors which were showered upon the .44 single action. Nobody seemed to want it for a target arm, perhaps because its trigger pull was not as easy as the s.a. At any rate it did not sell at anything approaching the rate of the smaller S&W double-actions, there being only 54,668 of the .44 Russian and 15,340 of the .44-40 manufactured. Mr. Wesson designed a variant of the latter revolver which carried several ounces less weight and was known as the “Wesson Favorite,” but comparatively few were made and they were numbered in the same series as the standard model. They are readily distinguished by the rebated cylinder, which is not unlike that of the 1860 percussion Colt. The outside diameter of the barrel was somewhat reduced and there was a sighting groove along the top rib like that on the Schofield .45.

The .44 double-action was carried in stock until 1913, although there was little call for it after introduction of the .44 New Century hand ejector. It could be obtained either in blued or nickeled finish and with rubber or walnut stocks. Barrels ran from four to six and one-half inches in length. In the longest barrel model, it weighed two pounds, five and one-half ounces.