The following information on the Smith & Wesson New Departure comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

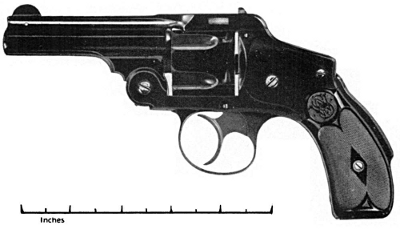

In 1887, Smith & Wesson brought out a revolver which still is as nearly foolproof as any ever made. It was the New Departure, alias the Safety Hammerless, also known in some of the western states as the “Lemon Squeezer.” It has been manufactured in five models, each differing from its predecessor in some small refinement.

Hammerless revolvers, or revolvers with hammers built wholly within the frame, were far from new. Two Englishmen named Harbey and Pennell made one to shoot cap-and-ball ammunition in 1853, and Pettingill patented one in this country in 1856 which was made in calibers up to .44. Although used to some extent in the Civil War, the Pettingill was fragile and never attained wide popularity.

The new arm was not notable because of the simultaneous extraction feature, which had been used on all Smith & Wesson revolvers since the .44 American. But the safety feature of the gun was ingenious, and it was the work of Daniel B. Wesson himself.

This consisted of a safety lever which projected through the back strap of the tang. It was linked with the safety latch and was so arranged that the hammer could not be drawn back until pressure was exerted on the safety lever by the shooter’s hand.

In the original design, a flat spring paralleling the inside of the tang brought the safety lever back to its original position after the trigger had been pulled, but the spring was inadequate for the job it was supposed to perform. Another distinguishing feature of the First Model is the frame post, which was made flush and notched to the latch with a Z-bar barrel catch post extending through the barrel strap, forming the base for the rear sight. The thumb piece for the catch release was placed some distance from the end of the barrel strap, but was moved closer on subsequent models.

The first hammerless model was designed to shoot the .38 Smith & Wesson cartridge, although several catalogues of the firm contain the following statement:

“The .38 Caliber Hammerless Revolver was brought out to meet the demand for a more powerful weapon than the .32 Caliber Safety but which has retained all the features which made the small gun so entirely satisfactory and safe.”

But if you are lucky enough to have a copy of the April, 1887, number of “The Rifle,” which is the direct ancestor of “The American Rifleman,” you will find a description of the revolver on Page 9, and on Page 13 the first advertisement:

“Caliber .38, Weight 18 1/2 oz. NOW READY. Calibers .32 and .44 in Preparation.”

The .32 appeared in February of 1888, but the .44 never got beyond the preparation stage.

The .38 was made with hard rubber grips in barrel lengths of 3 1/4, 4 and 5 inches—either blued or nickeled, and the original announcement in “The Rifle” stated: “The weapon described is for the use of the soldier, the police officer or for the use of those called upon to use this weapon of defense rapidly and effectively…”

Undoubtedly it was suited to the policeman or civilian who needed to shoot in a hurry at short range, but its characteristics do not seem to recommend it for military use. Nevertheless, it was considered seriously as a cavalry arm.

Along in ’88 or ’89, criticism was heard in Army circles that the regulation .45 revolver was much more powerful than it needed to be. Perhaps the idea came from England, where the .303 rifle had superseded the Martini. Some authorities took the position that a warrior would feel less resentful if killed or wounded by a small caliber bullet, and a certain Colonel Elmer Otis stated flatly that pistol fire should not be resorted to at ranges greater than 20 yards.

This was not bad military logic, for at greater ranges a shoulder arm can do a much better job than a hand gun. When a hand gun alone is available, despite the range, one which can be cocked and fired deliberately would seem to have the advantage—but the colonel thought otherwise and he recommended adoption of the Smith & Wesson New Departure revolver as the regulation cavalry weapon. Someone else fancied the new side-ejector Colt which shot the .38 Long Colt cartridge, and after due deliberation the Ordnance Board decided to give both a tryout.

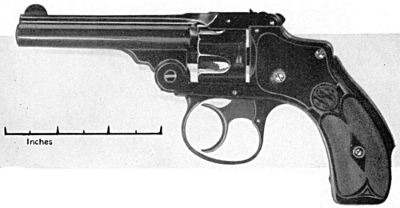

An order was entered for 100 Colts and an equal number of Smith & Wessons. To put them on an equal footing, the Board directed that the latter should have six-inch barrels the same as their competitors.

The Colt cartridge had the edge on the S&W, having a powder charge of 18 grains and a bullet of 150 grains; whereas the other had 15 grains of powder and 146 grains of lead. But the Colt barrels were bored oversize to .362 caliber, the bullets being .357 in diameter and depending on a hollow base for expansion—like the Civil War Minie balls. The S&W barrels were bored to exactly .357 and gave a tight fit to the square-base bullets.

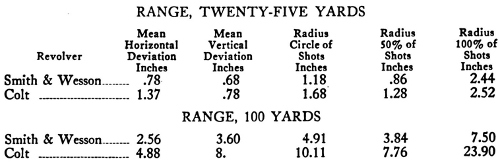

In the first test, which was for accuracy and fired from a machine rest, the Smith & Wessons won out, showing an appreciably smaller dispersion than the Colts. The figures, taken from “Modern American Pistols and Revolvers,” by A. C. Gould, 1894 edition, are as follows:

Mr. Gould’s observation should be added, that in these tests two bullets from the Colt revolver “keyholed” badly, obviously because of failure of the hollow-base bullet to expand.

Shooting into pine butts at 100 yards in a penetration test, the Colt’s heavier powder charge gave it the advantage, 3 3/4 inches to 3 1/4.

After that, both revolvers were fired by the same man in a test of loading, firing and ejecting. The Smith & Wesson won by firing 18 rounds, beginning and ending with empty chambers, in 52 1/2 seconds to the Colt’s 1 minute and 13 seconds. Twenty rounds were fired with the Smith & Wesson in 54 seconds.

The Board then directed that both revolvers be maltreated in a brutal and shameful manner. They were fired 50 rounds, cooled five minutes, and continued with alternate periods of fire and rest until 200 rounds had been fired. No cleaning was allowed, although they were shooting black-powder cartridges.

Early in the test the Colt’s rebound spring balked and the trigger had to be pushed forward by hand. The Smith & Wesson’s action refused to work at the 104th round, but after the cylinder was removed and wiped clean of fouling it functioned perfectly until the 140th round. At that point another cleaning was necessary and it went on to the end of the test without further trouble.

But the Board still was not satisfied, despite treatment which would have earned an enlisted man in Uncle Sam’s forces at least a term in the brig and possibly execution at sunrise. After the revolvers had cooled for 48 hours in their uncleaned state they were fired an additional 50 rounds in alternate series of 12 shots and five-minute rest periods. They functioned about as expected and had to be wiped off occasionally as in the preceding test. The Colt’s rebound spring again misbehaved and the trigger had to be given manual aid. Once the Colt’s cylinder failed to revolve, but after the sideswing action was opened and shut it worked satisfactorily.

More and worse cruelties were devised. The two revolvers were cleaned and then shaken in fine dust, after which they were brushed off by hand and fired for 12 rounds, then dusted again “to ascertain the combined effects of dusting and fouling,” then fired six rounds more. Aside from two instances when the Smith & Wesson trigger had to be given an extra pull to revolve the cylinder, it operated efficiently. But the Colt refused to work as a double-action revolver after the fifth round and had to be cocked by hand. Said the judges of the Colt, “In several instances the cylinder would not revolve without considerable assistance.”

Now the oil was removed from both weapons and they were immersed in a solution of sal-ammoniac for 10 minutes and exposed for 48 hours, after which 12 rounds were fired, without cleaning. Then the sal-ammoniac dunking was repeated and also the 48-hour exposure, the intention being to fire them 18 rounds if possible.

At this point the guns were dismounted and examined, boiled in a solution of potash to remove all oil, left overnight to dry and rusted again as before. But the members of the Ordnance Board were horrified to discover that the Smith & Wesson’s mainspring was broken. “The revolver was well rusted” and had to be coaxed with a mallet before the barrel catch and cylinder hook would operate. “The safety lever would not perform its functions until after some amount of manipulation.” A new mainspring was installed and 12 shots were fired without difficulty.

The Colt’s performance was somewhat better. “The revolver was found to be well rusted, but the mechanism operated freely and the 12 shots were fired without use of the mallet being necessary. The cylinder had to be assisted to revolve once, and the rebound spring failed to push the trigger forward three times.”

One would have thought that the inquisitors on the Ordnance Board would have been satisfied, but they were not. In the final test, the hand guns were rusted again as before but on account of the danger involved only empty cartridges were used. Sad to relate, the Smith & Wesson was cemented tightly by rust and the new mainspring was broken. It had to be laid aside as disabled.

Although the cylinder of the Colt could not be swung outward without persuasion from a mallet, and cartridges could not be inserted in the chambers until they were cleaned of rust, it then fired 18 rounds without difficulty—double action!

An inquest then was held by the Ordnance Board over the remains of the two guns. Final verdict was that the Smith & Wesson was not suitable as a military arm because of the multiplicity of its parts and its failure to survive the rust test. Apparently no attention was paid to the fact that the Colt had failed to get through the dust test, which represented a condition much more likely to arise than the sal-ammoniac dunking. In any event, it was adjudged the winner and became the regulation hand gun of the United States Army.

The Colt revolver continued in use by the Army until the Philippine Insurrection and built a fine reputation for itself, as well as for the .38 Long Colt cartridge. Nobody seems to have had the slightest curiosity about the combinations efficiency as a man-stopper, however, and the Spanish-American War did not provide any occasions for disillusionment. Hardly a revolver cartridge was expended in that brief struggle except for target practice, the issue being settled by shoulder arms and artillery. Thus it was not until our soldiers engaged in close-in fighting with the Tagals and the Moros, as we will see later, that the deficiencies of the cartridge were revealed.