The following information on the Smith & Wesson Regulation Police comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Colt hand-ejector pocket revolvers in .32 caliber had been made for about 15 years and Smith & Wesson side-swingers had been on the market for four years in larger caliber before the latter decided to adapt the system to a .32 pocket revolver. The design presented no special problem, as the gun would be simply a smaller model of the .38 Military and Police Model. But the ballistics department was requested to devise an improved cartridge before the new model was placed on the market, the old .32 S&W cartridge used in the jointed frame models being underpowered.

The new cartridge contained 13 grains of black powder and a 98-grain bullet with rounded end. It had the same diameter as the smaller cartridge so that it could be used interchangeably with it. Ballistically, it did not differ greatly from the Civil War rim fire .32 long, though the bullet was heavier by 8 grains. But in accuracy, the new ammunition was greatly superior and it is still rated high in the fifth column of those tables put out by cartridge manufacturers which show how far away a bullet is dependable with the proper aim and trigger pull. Its energy is only rated at 117 foot pounds, but a .32 is not suitable for big game hunting in any event.

Probably due to corresponding changes and improvements in the .38 Military & Police Model, the .32 Hand Ejector followed the same process of evolution. Most of these changes would be overlooked unless you took the action apart. Revolvers bearing serial numbers from 1 to 19,425 were made before any changes were made. Then, among other things, the cylinder stop notches were lengthened to fit an elongated stud slot, contributing to a better alignment of cylinder and barrel. In this form, it ran from 19,426 to 61,126, which gives some indication of its popularity. The second group of changes affected revolvers of this model running to 95,500 and all were of minor importance. As the parts catalogue puts it, however, “As there have been numerous changes in this arm it is advisable to send in the old part when ordering duplicates to avoid delay and chances of error.” A glance through the list of changes, all the way down through number six, will bring out all your compassion for the plant’s service department. The model had 50 parts, and each of them had to be kept in a special bin or compartment. Some were small enough to go through the eye of a fair-sized needle. Subsequent changes and serial brackets were as follows: Third change, 95,501-96,125; Fourth change, 96,126-102,500; Fifth change, 102,501-264,856; Sixth change, 264,857 ad infinitum, as they are still being made that way.

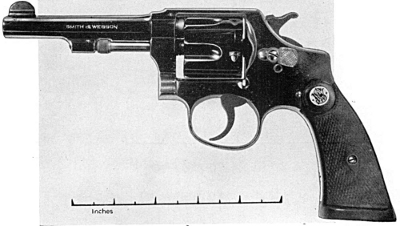

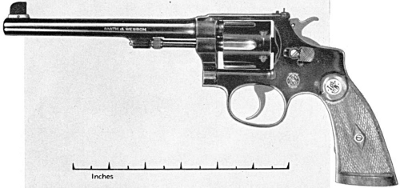

This category is a little hard to decipher, particularly in view of the fact that the Third Model hand-ejector, alias the .32 Regulation Police Model was announced in February, 1917. Presumably there was a Second Model, but the records covering it are incomplete. The Regulation Police Model was built with a square butt and appealed to shooters with large hands. It follows in the same series as the .32 Hand Ejector, with its numerous changes. Listing is unnecessary, as it is still being made.

Both models are offered with barrel lengths running from 3 1/2 to 6 inches and a Regulation Police Target Model is equipped with a Partridge front sight and an adjustable rear sight. They are sixshooters and are available both in nickel or blued finish.

The S&W .32 Long has the same outside dimensions as the .32 Colt Police Positive, or New Police, but some manufacturers produce the Colt cartridge with a 100-grain bullet. Colonel Hatcher’s figures for the S&W are 790 f.s. and 140 foot pounds of energy, though the Smith & Wesson ballistics table credits it only with 734 f.s. and 117 foot pounds. Just to be different, the Winchester table gives it a velocity of 817 f.s. and energy of 143 foot pounds.

The Colt cartridge is listed by Colonel Hatcher as exerting 720 f.s. of velocity and energy of 120 foot pounds, but Winchester only concedes it 706 and 109 respectively and Smith & Wesson omits its ballistics from the table, although it is mentioned as an alternate cartridge in the catalogue. Since the highest figures for either cartridge are well within safety limits, there is no reason to suppose that they are much at variance ballistically. For shooters who are not inclined to worry about the wear and tear on the barrel, a metal pointed cartridge is available in this caliber which performs the same as the other two.

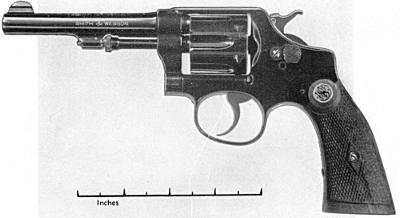

Smith & Wesson introduced the .38 Regulation Police Model simultaneously with the .32 Regulation Police. It differed from the smaller gun only in chambering five of the larger cartridges instead of six. Its heat-treated chrome steel cylinder and four-inch barrel was procurable in blued or nickeled finish and the grip had a square butt. More recently, due to the trend toward short-barreled revolvers, the round-butt frame has been attached to a two-inch barrel and the arm is officially known as the .38/32 2″. It measures up very well with Colt revolvers of the same type and is an accurate shooter. Both the .38 Regulation Police and its short-barreled mate are still on the active list and hence serials would be meaningless at this time.