The following information on the Smith & Wesson Revolving Rifle comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

Smith & Wesson adapted their single-action revolver design to what they termed their “Frontier” Model in 1885. Identical in most respects with the .44 models chambering the Russian cartridge, its cylinders were 1/8 inch longer and the top strap and receiver were lengthened correspondingly to take the .44/40 Winchester rifle cartridge. Intended to compete with the Colt Frontier revolver chambering the same cartridge, it never became popular. Only 2,072 were produced and the majority of them were taken out of stock and rechambered for the Russian cartridge.

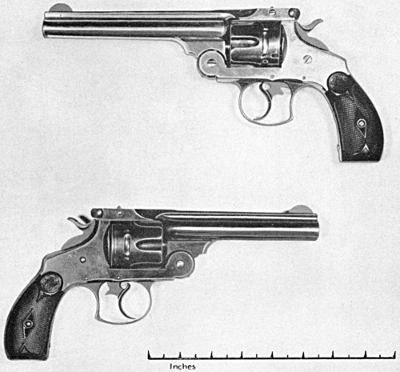

Smith & Wesson, Double action, .44 Revolver “Navy Model” .44 Russian cartridge.

Note: The length of cylinders in 1 and 2 is the same.

Mention has been made of the .38/44 manufactured on special order for Ira Paine. The firm recognized its fine performance and built 1,023 of them with 1-7/16 cylinders and 390 with 1-9/16 cylinders to shoot the Paine cartridge. A round-ball gallery cartridge with the same case length was also developed, but the barrel fouled so badly after a few shots that it never became popular and was discontinued in 1910. The bore diameter approximates that of the .38 special and a few of the model have been rechambered to take that cartridge.

Along with the .38/44, a .32/44 was put in production. This arm also chambered a cartridge in which the bullet was wholly encased and did not touch the cylinder wall. It carried 10 grains of powder and 83 grains of lead, and a round-ball cartridge was supplied for gallery work. Two thousand, six hundred and twenty-one were made with 1-7/16 cylinders, and 299 with 1-9/16-inch cylinders. As in the case of the .38/44, none was made after 1910.

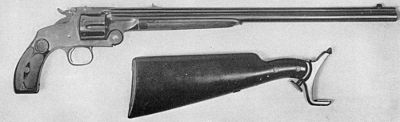

Although Smith & Wesson supplied extension stocks to fit the .44 single-action revolver, few of them were sold. This practically exhausts the subject of the New Model Russian frame, except for a model which was not a hand gun at all, properly speaking, but a shoulder arm.

It was around 1870 that Frank Wesson, a brother of Daniel B., began putting out what he called a “pocket rifle” shooting the .22, the .25 Stevens and the .32 rim fire cartridges. The weapon was simply a pistol with an elongated barrel, and the idea dated back at least to flintlock days. When the percussion system of ignition was developed it appeared again, and various gunsmiths produced them under the designation of “buggy rifles.” Colt and Remington had manufactured such arms during the Civil War to shoot their .36 and .44 cap-and-ball ammunition, without notable success, and a few had been adapted for the metallic cartridge.

In 1880, however, no small caliber repeating rifles large enough for small game shooting were available, and Smith & Wesson decided to supply the deficiency. As a foundation arm they selected their improved Russian Model revolver.

A cartridge somewhat more powerful than the prevailing .32 was developed, with 17 grains of powder and 100 of lead—not too long for the .44 cylinder, which was chambered to take the new ammunition. The butt of the gun was slotted and provided with a wooden stock and a solidly fitting clamp. The barrel was fashioned in two sections, threaded together about two inches forward of the breech, at which point was fitted a large circular boss to which was attached a mottled-rubber fore end.

Barrel lengths of 16, 18 and 20 inches were offered and much attention was given to the arm’s sighting qualities. Not only was a peep sight furnished, but an open sight on the barrel and a globe sight in front—the latter being of crystal with a black spot for increased accuracy. All metal parts were finished in the well known Smith & Wesson blue-black.

When the gun was turned over to the testing department, some remarkable scores were recorded. One shooter turned in 23 successive holes in a four-inch bull at 110 yards, and all concerned spoke highly of the new rifle’s shooting qualities at distances up to 300 yards.

Apparently Mr. Wesson took the testing records at their face value and did not discuss the new gun with the men who had made them. If he had, he would have learned that their opinions of the arm coincided with those Civil War veterans who had shot the Colt revolving rifle of about 1861—which opinion was far from flattering. Fact was that a rifle with an interstice between chamber and barrel was unpleasant to shoot. Some leakage of flash and gas was inevitable, no matter how closely the parts were fitted. This feature in a hand gun held at arm’s length is not objectionable, but when the spurt from the exploding cartridge takes place six or seven inches from the shooter’s face it is a distinct nuisance.

The Smith & Wesson rifle in an attractive leatherette case and priced at $25 was not a bad buy, but only 977 were manufactured from 1880 to 1885. Around the plant the story still is told that most of them were bought by the Clan-na-Gael, an organization of fire-eating Irishmen closely related to the old Molly Maguires, which had visions of freeing the Emerald Isle from British yoke. It was a good thing for their side that they didn’t start their private war with such equipment.

The cartridge for the S&W rifle was more popular with the shooting public. It fitted the .32/44 revolvers already described and a number of Stevens single-shot pistols were adapted to chamber it. When the superior .32-20 cartridge was developed, the “rifle” ammunition became obsolete.