The following information on Smith & Wesson tip up revolvers comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

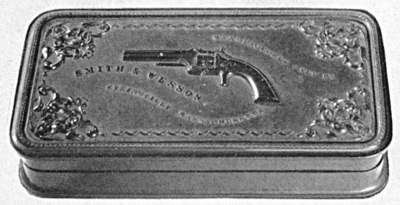

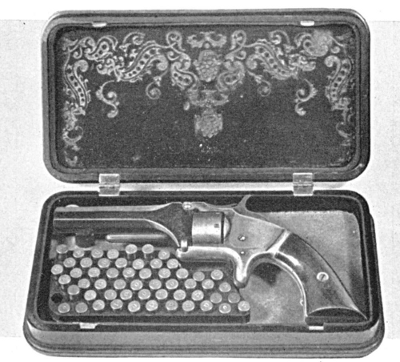

The day they filled their first order for their new revolvers must have been a proud one for the partners. It was a day for which D. B. Wesson long had waited, and although the weapon they were producing was not calculated to stop the charge of a rhinoceros, it was a sweet little number, with its bronze frame (called brass at that time) and its square-ended walnut stock, “piano finished.”

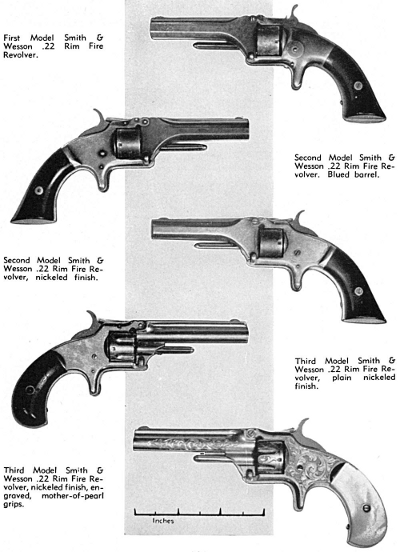

The gun illustrated is numbered 2130, a really early one, and it has had a lot of handling. But enough of the original finish remains to show that the frame was nickel-plated and the cylinder and barrel were in that brilliant “midnight blue” which has been the despair of other arms manufacturers.

This was the first of the famous S&W “tip up” models which were continued in production until 1869. The barrel is jointed to the frame at the front of the top strap and held at the bottom by a spring latch arrangement which releases upon upward pressure. On the left side of the frame is a circular plate secured by the screw which is the axis of the hammer and its assembly. Removal of this plate affords—theoretically—access ·to the revolver’s innards, but the port under the plate is only half an inch in diameter and adjustment of the cylinder pawl and trigger through such a tiny orifice is an operation few watchmakers would care to undertake. This is one of several features discontinued on later models.

Colt’s basic patents had expired when this revolver was issued and nothing would have prevented use of the straight-lever type cylinder stop, but for some reason unknown today the partners saw fit to substitute a system less dependable for bringing the chambers in exact alignment with the barrel. In a groove at the top of the upper strap of the frame was a straight spring which exerted pressure on the slots in the cylinder by means of a lug. Pressure was removed by raising the hammer—itself a two-part, jointed affair which opened somewhat like the mouth of an alligator. This questionable improvement was duly patented in 1859, notwithstanding the fact that infringement was perhaps the last thing the partners had to fear.

Clear proof of the defects inherent in early cartridge ammunition is found in the ratchet assembly of this revolver. All previous revolvers from the first Paterson Colt had ratchets which were integral parts of the cylinders, but this gun had a circular recoil shield which engaged the cylinder by means of a lug, doubtless to prevent jamming of the action in case the imperfectly-made cartridges bulged at the head. Improvement in the quality of cartridges enabled the partners to eliminate this feature in later models.

Barrel of the gun was octagonal, with a rib running along the top, and its length was 3 and 3/16 inches. A lunar-shaped front sight was inserted in a slot parallel to the bore and the rear sight was a minute notch in the uptilted end of the cylinder stop spring. Extruding beneath the barrel like the proverbial sore finger, and marring the streamline effect of this trim little gun with its stud trigger, was the ejector rod. But whatever it lost thereby in beauty it gained in utility, and it was some time before a better method of extracting cartridges was developed.

Rifling in this gun consisted of three grooves, with lands of equal width. Pitch consisted of one turn in 24 inches, left hand twist, like the Colt arms of that time. Smith & Wesson’s next model employed a right hand twist and all subsequent models, with one exception, have adhered to that system of rifling.

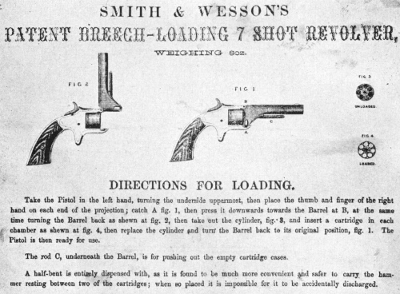

Cylinder of the first S&W revolver was bored for seven cartridges and engaged the frame by means of a hemispherical knob, being held in place at the rear by a column projecting through the axis of the recoil shield. No half-cock or safety notch was provided, the manufacturers excusing the omission in the following words included in the directions for loading:

“A half bent is entirely dispensed with, as it is found to be much more convenient and safe to carry the hammer resting between two of the cartridges; when so placed it is impossible to be accidentally discharged.”

The stud-type trigger on this gun, in the place of a bowed trigger guard, was not a novelty, as it dated back at least to the flintlock period. Extra cylinders, which could be loaded in advance, carried in the pocket and substituted for the empty cylinder in a moment’s time, helped to make the tip-up model popular—along with the very obvious advantages of waterproof cartridges.

Although intended purely as a pocket arm and built with a proportionately small grip, the gun illustrated will still do very fair shooting at 10 or 15 yards, in spite of its rudimentary sights. At greater distances it can hardly be described as a lethal weapon. In a day when large-calibered guns were the rule, it must have been regarded as little more than a toy.

Messrs. Smith and Wesson were acutely sensitive to the principal weakness of their new product. With the end of the Colt monopoly, numbers of manufacturers were turning out hand guns with a real wallop, albeit they didn’t shoot waterproof metallic cartridges. To possess such an exclusive feature only to see it wasted on a child’s-size model was enough to drive any inventor to the corner saloon.

Prime difficulty encountered by the partners in their efforts to build a bigger gun chambered for a he-man cartridge was the drawing and tempering of the copper case. They found it next to impossible to produce a case which was strong enough to withstand a heavy charge of powder and at the same time thin enough to yield to the blow of the revolver hammer. Copper is tricky stuff and it was several years before a system of drawing and annealing was perfected which left the cases rugged enough to withstand charges larger than that of the feeble .22.

Not until June of 1861, after the secessionists had had their way and history’s greatest Civil War was in its opening phases, did Smith & Wesson bring out what they called their Model 1 1/2 revolver. This arm did not measure up to advantage with the 1860 Model .44 of Colonel Colt, or the equally husky Beale patent Remington of the same caliber. It was only a .32, actually with a bore diameter of .313, but it shot a 90-grain bullet backed by the authority of 13 grains of powder, which at least was a step in the right direction.

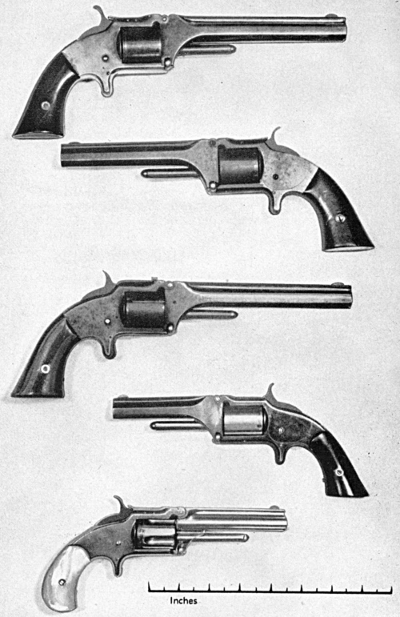

Second from top: First Model Smith & Wesson .32 Long Rim Fire Revolver, blued finish, 5-inch barrel.

Third from top: Variant Smith & Wesson .32 Long Rim Fire Revolver, blued finish, 6-inch barrel, short spurred hammer and different cylinder stop and rear sight.

Second from bottom: Second Model Smith & Wesson .32 Short Rim Fire Revolver, blued finish.

Bottom: Third Model Smith & Wesson .32 Short Rim Fire, nickeled finish, mother-of-pearl stocks.

The new weapon was made with either a five or six-inch barrel and weighed approximately the same as the Colt .31, which was what most commissioned officers of the Union Army carried. Outside holsters were prohibited, and the well dressed officer followed the example of the British military in avoiding a weapon which would give an unsightly bulge to his uniform. The Model 1 1/2 could be loaded much more quickly than any cap-and-ball revolver and its ammunition was waterproof. For these reasons, Smith & Wesson had to go on night shift and their .32’s were snapped up at premium prices by Army and Navy officers—even though the weapon’s effectiveness in stopping an onrushing foe depended on hitting him in a vital spot.

Many of the freaky features that had distinguished the first model S&W were discontinued in the second. The jointed hammer had been scrapped in favor of a flange on the top which did as good a job of raising the cylinder stop. The slender spring of the latter had been replaced by one of split design and sturdier construction.

Steel was employed for the frame instead of bronze, and access to the interior mechanism was by means of an irregularly-shaped side plate which exposed an opening through which a man could work with some comfort. Cartridge ammunition having by this time been so improved that bulged heads were of infrequent occurrence, the recoil shield was omitted and the ratchet formed part of the cylinder as in other revolvers. On the earlier model the frame had been rounded, but on the new .32 it was flat on both sides.

One chamber of the cylinder had been sacrificed in boosting the caliber from .22 to .32, so this model was a six-gun. There was no gas ring on the cylinder and the designer still had failed to provide a safety notch for the hammer—so that the arm was as great a menace to its owner and to innocent bystanders as its predecessor had been.

Most hammers for this model had a conveniently shaped thumb-piece, but in the stress of peak production one batch was fitted with hammers left over from a lot made for the lever-action repeating pistols not intended to be cocked by thumb. This feature must have embarrassed owners who tried to do any fast shooting.

A defect developed on the “Old Model” .32 which was not corrected in that or succeeding models for a long time: There was considerable tolerance between the cylinder and the top strap of the frame, and when much shooting was done the powder fouling so gummed the action that the cylinder had to be revolved by hand.

This model was finished in various manners. Sometimes the metal parts were blued and sometimes they were nickeled, while as often the barrel and cylinder were blued and the frame nickeled. Stocks were of highly polished rosewood.

Altogether, 76,502 of this model were produced, the last in 1874.

As a companion model to the No. 2, Smith & Wesson produced their Second Model .22, a reduced replica of the .32 except that the frame of the smaller gun continued to be made of bronze. Since they were numbered in the same series with the First Model, it is impossible to say today how many of each model were built. Together, however, the two models aggregated 126,439.

The Second Model was produced from 1861 to 1868 and many were carried by privates and non-commissioned officers of the Union Army—as well as by some officers—as vest-pocket weapons.

In December of 1861, occurred the only military casualty of record during the Civil War—inflicted by an S&W .22. The incident took place in Cortland, N.Y., where the 76th New York Volunteers were recruiting. Although the regiment had not yet been accepted formally as a United States force, officers had been elected (a custom of volunteer groups of that time) and Colonel Nelson W. Green had been made commanding officer.

The records of the regiment do not reveal the particular infraction of the rules committed by a certain Captain McNett while the regiment was on parade, but whatever it was it caught the watchful eye of the newly-elected colonel who evidently felt that the time had come to give everybody a little lesson in discipline.

He therefore indignantly ordered the offender to go to his tent and consider himself under arrest. But Captain McNett had been accustomed to calling the colonel by his first name until just a few days before and he failed to take the order seriously, whereupon Colonel Green produced a Smith & Wesson .22 and fired upon the offender.

The bullet took effect somewhere in the region of Captain McNett’s chin and lodged in his neck, causing him to stagger over to the nearest camp stool to the accompaniment of a concerted gasp of horror from the ranks of wide-eyed soldiers.

A doctor appeared on the scene to give the captain first aid, and the following day he was able to go down to the district attorney’s office and swear to a warrant for the colonel’s arrest. The grand jury which chanced to be in session took immediate notice of the incident and voted an indictment charging the colonel with felonious assault, which must have been quite embarrassing for the head-man of a regiment of volunteers.

Colonel Green supplied bond pending his trial, but the times were too critical to allow for legal formalities and the regiment soon was on its way to face deadlier missiles than .22 bullets. When the two officers returned home in 1866, the trial finally was held; but the jury was unable to agree upon a verdict. Perhaps some material witnesses were missing, perhaps the excellent records of both complainant and defendant swayed the jurymen. More likely, however, five years of bloody war had made a .22 caliber bullet wound appear too trivial to be the subject of court action.

Assisting the sale of the tiny Smith & Wessons was the ignorance of the general public in regard to firearms. To the average man, a revolver was a deadly weapon and the size of the charge did not interest him greatly. This fallacious opinion was held by criminals as well as minions of the law—otherwise a certain deputy sheriff in an upstate New York county would never have returned alive from a foolhardy expedition he made armed only with “one of them new-fangled ca’tridge revolvers.”

This chap had been detailed to run down the local Public Enemy No. 1, so he took his trusty .22 and followed the man’s trail to an isolated mountain cabin. The criminal was known to be heavily armed, so the deputy cautiously “snuk up” on the cabin, kicked open the door and “threw down” on the burglar with his Smith & Wesson. The fellow dropped the axe he had seized as the door burst open and docilely marched to the deputy’s horse and sleigh with his arms upraised in token of the S&W’s authority.

If the Smith & Wesson .32 played a major role in the Civil War, the records are curiously silent about it. As already noted, it was an officer’s weapon and virtually all illustrations of battle scenes show the officers brandishing swords instead of revolvers. The sword seemed to be much more inspirational and decidedly more romantic. Custer and other cavalry leaders of both forces favored large caliber hand guns, which were available in quantities only in the percussion type at that time, as we will show later.