The following information on the S&W Terrier and other short barreled Smith & Wesson revolvers comes from Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by Roy C. McHenry and Walter F. Roper. Smith & Wesson Hand Guns is also available to purchase in print.

In the early nineteen-twenties, the Colt Corporation began to produce a short-barreled revolver at the behest of the Post Office Department. A gun was needed for railway service men which would be convenient for pocket carrying but husky enough to qualify as a man-stopper. The Colt weapon designed to meet these specifications had a two-inch barrel and chambered the .38 Police Positive and .38 Smith & Wesson cartridges and was known as the “Bankers’ Special.” A little later, snub-barreled Colt Police Positive Specials were turned out under the nomenclature of “Detective Specials.”

Considerable demonstrating—much of it by the well known J. R. Fitzgerald of the Colt Corporation—was needed to convince the sleuths that accurate shooting could be done with such stubby affairs. “Fitz” insisted that his prospects do the shooting and soon convinced them that the short barrel was not fatal to accuracy.

No doubt many of the short-snouted guns were put to less legitimate uses, among them being the Chinese tong wars of the west coast. The Chinese have laid claim to prior use of almost every outstanding invention, including the mariner’s compass and gunpowder, and the so-called “belly gun” was no exception. Its use does not date back to the Ming dynasty, however.

Tong wars were carried on in this country, as in China, by hardened wretches known as hatchetmen—from the implement originally used to dispatch their victims. After a time they began to modernize their methods and found that revolvers, while noisier, were quicker and surer than hatchets. But while they preferred hand guns of .44 or .45 caliber, the long barrels of these implements were difficult to disguise inside the sleeves of their kimona-like garments. Hence they filed off all but a couple of inches of barrel and continued to get results they considered highly satisfactory at the ranges they considered proper.

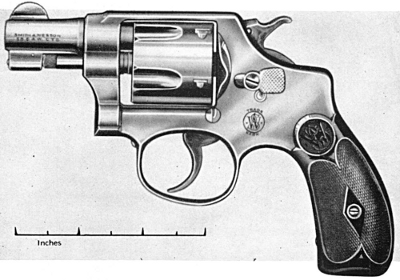

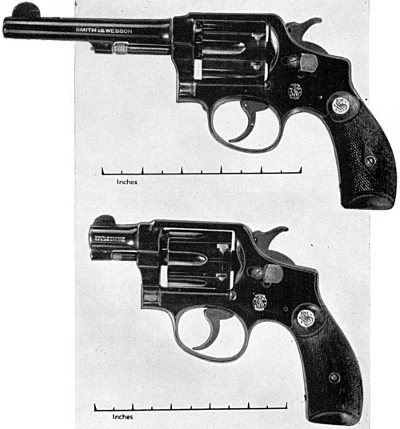

Smith & Wesson did not succumb to the fad for short-barreled revolvers until 1936, when the firm brought out what was termed the “S&W .38/32 2″,” later christened the “Terrier” which was simply the round butt Regulation Police Model with a two-inch barrel. It chambered the .38 S&W, its companion cartridge, the .38 Colt Police Positive and the .38 S&W Super Police with its blunt-nosed 200-grain bullet. Its weight of 17 ounces makes it an attractive pocket arm.

The firm also manufactures what it calls its “Kit Gun,” which in outward form is the round butt Regulation Police Model bored and chambered for the .22 long rifle cartridge. It is a neat hand gun for packing in a week end or vacation grip and can be used with Hi-Speed cartridges for target shooting at more than 25 yards.

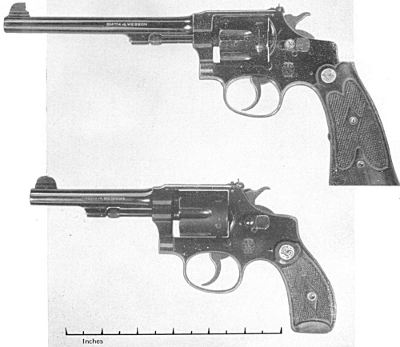

The corporation produced its round butt .38 Military & Police Model with a two-inch barrel in 1938. It had not been claimed hitherto that the .38/44 cartridge was suitable for the K Model .38, but a circular describing the two-inch barrel variety stated that it would handle the heavier cartridge safely. This being so, it should do equally well in the later K Model .38 Specials with heat-treated cylinders, although it would have an unpleasant recoil with either length of barrel. With the two-inch barrel, the gun’s weight is 28 ounces, only three-quarters of an ounce less than the longer-barreled model.

At the present writing (1944) it is next to impossible to buy a new Smith & Wesson revolver of any kind, and just as hard to get ammunition. What Smith & Wesson has been producing since some time before the United States entered the war is a “military secret,” but what they are like and what they do cannot be told in full until the war is over.