In a previous article we read what C. S. Landis had to say about trigger control and offhand shooting posture. Today we will continue in a similar vein and take a look at what Townsend Whelen has to say about marksmanship for hunters and marksmanship in the wilderness.

The following excerpt comes from the twelfth chapter of Wilderness Hunting and Wildcraft by Townsend Whelen entitled Wilderness Marksmanship.

WILDERNESS MARKSMANSHIP

“The rifle is a noble weapon. It brings us pleasures that no scattergunner can ever know. A shotgun takes you into cultivated fields, or into those narrow wastes within sight and sound of civilization. But the rifle entices its bearer into primeval forests, into mountains and deserts untenanted by man. To him in whom the primitive virtues of courage, energy, and love of adventure have not been sapped there is scarce a joy comparable to that of roaming at will through wild regions, viewing the glories of the unspoiled earth, and feeling the inexpressible thrill of manliness sore tested by privation and hazard, but armed and undismayed.”—Horace Kephart.

Basic.—Good shots are made, not born. An untrained man instinctively does the wrong thing in firing a rifle. He gives the trigger a sudden pressure, a pull, or jerk when ready to fire, which causes the shot to go wide of the mark by disturbing the alignment of the rifle. The instinctive dread of recoil increases this tendency, and also causes flinching. But with proper instruction any man who is physically fit to hunt big game can become an excellent and reliable rifle shot. Intelligent and educated men can develop themselves with little assistance into first-class marksmen by following the Army training regulations on this subject as a guide,* and by practice in conformity with the principles laid down in these regulations. Study of these regulations, a little home practice, and about ten afternoons on a rifle range or in the country will perfect most men to such an extent that they are far better shots than the majority of sportsmen and guides. But there are some men who cannot learn practically from printed instructions, and for such an individual coach is necessary.

* “U. S. Army Training Regulations No. 150-5, Marksmanship, Rifle, Individual,” and “U. S. Army Training Regulations No. 150-10, Marksmanship, Rifle, General.”

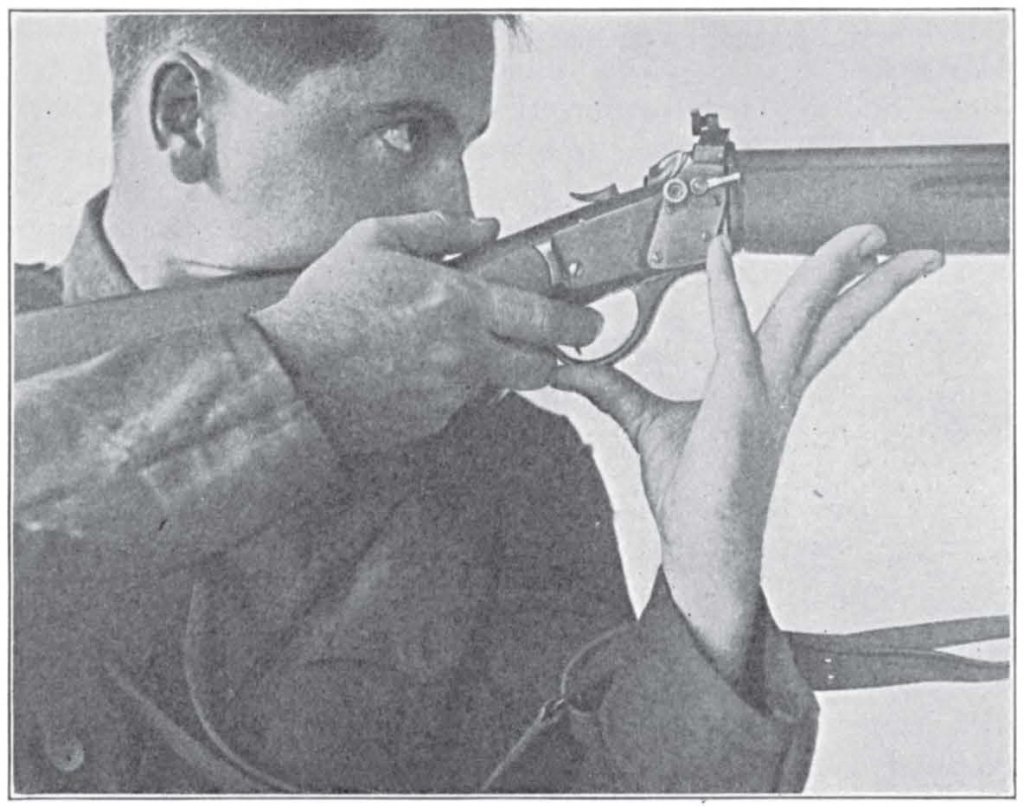

The essentials of good shooting are that the individual must know ( 1) how to hold the rifle with a fair degree of steadiness in each of the firing positions; (2) that he shall know how to aim accurately and consistently; and ( 3) that he shall know how to squeeze the trigger without disturbing the steady hold and accurate aim. Furthermore, he must learn by practice how to coordinate these three essentials-holding, aiming, and trigger squeeze. He must also master the functioning of his rifle and the “Mechanism of Rapid Fire.” Until a man has mastered these he is still in the beginner’s class, and is not prepared to undertake practical shooting of any kind.

It is easier to teach a man to shoot who has never previously had a rifle in his hands than a man who has done a lot of promiscuous shooting without a guide or intelligent instruction, and who has developed many faults. Some faults in rifle shooting, particularly those concerned with the three essentials, are absolutely detrimental to progress and very difficult to overcome. A sportsman should never start rifle practice without a proper guide or a qualified instructor.

The ultimate object of all instruction and practice with the rifle is to develop in the individual the ability to hit small, indistinct targets at unknown ranges, and to hit them quickly and repeatedly, even though they be moving.

I have often seen it stated in print that a good target shot is seldom a good game shot, and vice-versa. This is not true, and men who state such things are neither one nor the other. Exactly the same qualifications, skill, and knowledge are required for hitting a target as for hitting game, and once a trained marksman has become accustomed to his surroundings he will do as well in one form of shooting as the other. But it is first necessary that he be basically trained, and the instruction in this is given in detail in the Army training regulations. It is true that the so-called “target shot” who has never done any shooting except slow fire at a bull’s-eye target is often too slow and deliberate for success in shooting at game. But such a man is not a real target shot. He has never proceeded beyond the A.B.C. of target shooting. He is still in the beginner’s class, for his basic training has not been completed. Basic training includes the rapid functioning of the rifle, the mechanism of rapid fire, the learning of a quick but perfect trigger squeeze, and requires considerable practice at rapid fire.

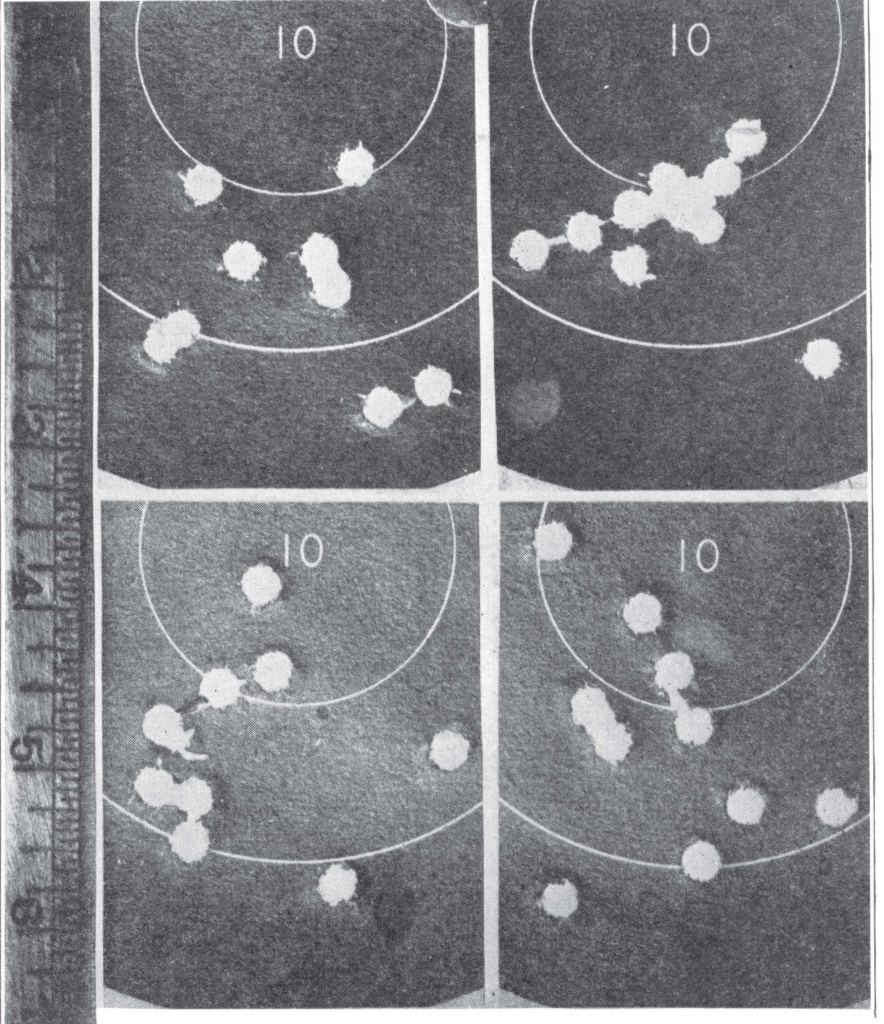

Today we see more and more tendency to confine target shooting to the prone (lying) position only. This is to be deplored. A man should be able to shoot well and quickly in any position. In days gone by in the Army we were required to practice and qualify at rapid fire in the standing position. The target was silhouette of a kneeling man at 200 yards, and it appeared in view for twenty seconds during which time the marksman was required to fire five shots at it. Similar practice was had in the kneeling, sitting, and prone positions, but the basic position for rapid fire was standing. I know of no form of shooting better qualified to teach really practical rifle marksmanship. When a man can “stand up on his hind legs” and hit a kneeling silhouette five times in twenty seconds at two hundred yards he is a first-class game or target shot. Such skill is by no means beyond the capabilities of any man, although it does require almost a season’s practice. But before one can profitably indulge in such practice he must have acquired the ability to put 80 percent of his shots in the regulation 10-inch bull’s-eye at 200 yards, slow fire. The trouble with the so-called target shot is that he pursues the system so far, and then instead of proceeding to practical shooting, he confines all his future practice to trying to put 99 per cent of his shots in that bull’s-eye, slow fire; one minute per shot. Bull’s-eye shooting is a fascinating game, but it is not practical rifle shooting, it is not military target shooting, and it is of little use in game shooting. It is like learning to say the alphabet forward and backward but never learning to read. A man who has mastered slow-fire target shooting only is not a target shot. A hunter who has never mastered the basic essentials of good marksmanship is not a game shot, although he may be living in that delusion caused by one or two lucky or fluke shots at game. The sportsman who desires to become a good game shot with the rifle should obtain the Army training regulations and proceed to develop himself in all the essentials and fine points of slow and rapid fire by intelligent practice, or he should obtain the services of an experienced coach to teach him these things. After that he will have learned enough to enable him to perfect himself in any form of rifle shooting which he desires.

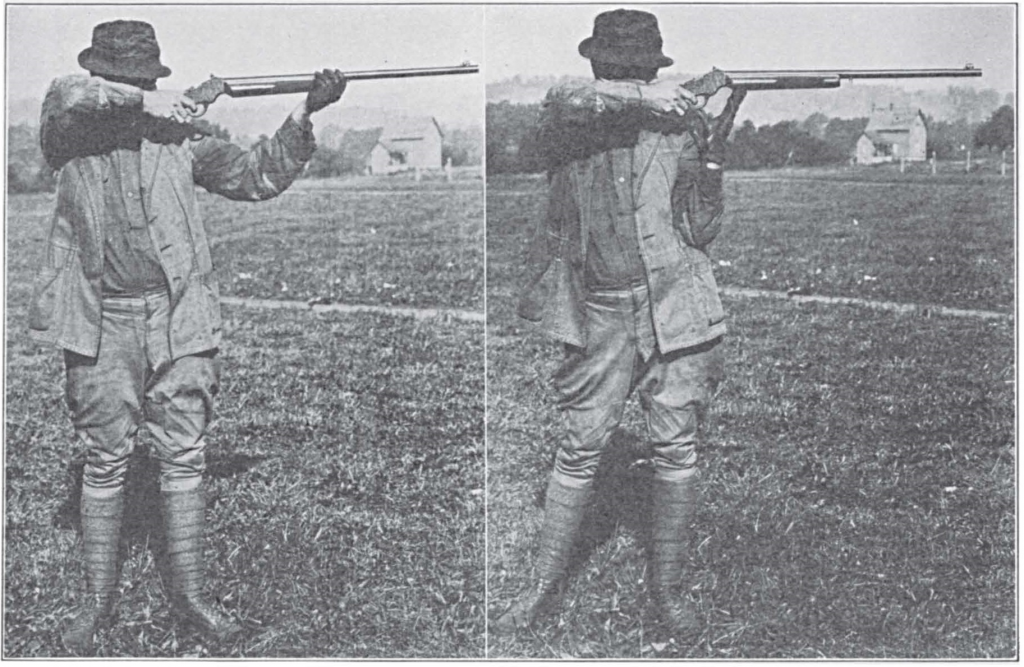

The Standing Position.—In woods hunting one almost always has to take his shots standing. Usually there is no time to assume any steadier position, and if one did sit down or lie down the brush would almost always interfere with the view. The artist loves to depict the hunter kneeling, but almost all trained riflemen find that the kneeling position is much more difficult than to fire standing, and that it takes a comparatively long time to steady down to a good hold and aim in that position. So the kneeling position is seldom used by good shots. One day I was still-hunting moose with my old friend Charlie Barker. We had stopped for a short rest and were sitting on a log watching an ermine hunting mice, when suddenly my sub-conscious mind seemed to tell me that there was something off to our right. I whispered to Barker and got up and strolled over that way quietly. A few yards and I saw the gleam of a big pair of moose antlers appearing like old ivory and glistening above a bush a hundred yards away, then I made out the face and nose of the moose. At once, standing where I was I aimed where I assumed the point of the chest must be, and squeezed off the trigger. Instantly my hand flew to the bolt handle, and by that sleight-of-hand motion known to trained riflemen, I threw in another cartridge and caught the bull as he turned sideways to run off. Almost instantly I was ready to fire a third shot which caught the moose when he had turned tail and was about to leave. At this shot the bull reared up and fell down with a crash, and at my elbow Charlie Barker yelled, “You’ve got him by gosh, you’ve got him!” It was exactly like the old days on the Army Infantry Rifle Team, rapid fire, 5 shots in 20 seconds, at the silhouette of a man kneeling at 200 yards—only it was easier. In those days, which the Englishman would call “salad days,” we youngsters on the team used to be willing to bet a dollar any time that we could make a possible (five hits) at this 200 yard rapid fire.

There is another little lesson for the beginner to learn from this incident. It pays to keep pumping in accurately aimed shots as rapidly as possible while the game remains on its feet.

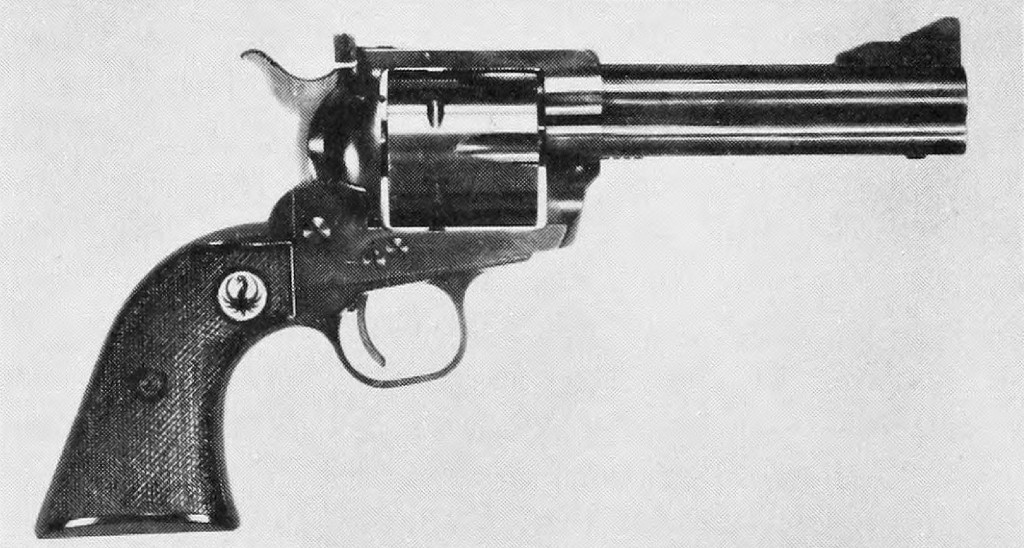

Confidence.—A big-game hunter should have that confidence with his rifle which comes only through perfect familiarity with it. Only thus will he be able to use it with effect, particularly in moments of excitement. The lack of this confidence is partly the cause of buck fever and of those unfortunate incidents which can be related by every guide of experience which happen when the game is apparently within grasp. I have heard of hundreds of these incidents, among which the following will suffice to illustrate the point. A Montana guide lead his sportsman up to within 50 yards of a bull elk. Upon being told that it was an elk with a fine head and that he must shoot, the sportsman placed his rifle to his shoulder and pumped every cartridge out of it without firing! Another incident happened with a sportsman who was considerably familiar with rifles, but not quite enough so. His guide showed him a moose within easy range. The sportsman immediately got the bolt of his rifle tangled up in his belt and when the guide had untangled that he unlocked the rifle to fire, but immediately locked it again, and tried to pull the trigger but could not. However, after a while he got straightened out and killed the moose which had most accommodatingly waited for him to do everything wrong at least once. Incidents of this kind are most unfortunate, and they leave a black spot on one’s vacation even if no one knows about them but the individual. And such an incident might, in fact, often does, happen on the one shot that the hunter gets on a hunt that he has perhaps planned for years. The point is that they scarcely ever happen to men who have made themselves perfectly familiar with their rifles by a dozen or so afternoons of range practice, intelligently applied, before starting out, and they do very frequently happen to those who neglect to take such practice.