After going to the range yesterday and shooting some disappointing offhand groups, I decided to hit the books and see if I couldn’t learn something to improve my posture for offhand shooting and trigger control.

The following is an excerpt I found from Small Bore Rifle Shooting by Edward Crossman on the subject of offhand shooting and trigger control which I think might help those of us struggling to improve our groups from the standing position.

STANDING, OR OFFHAND

This takes one of two forms, in a broad classification. Success in either one is a matter of trigger control; no man can hold steadily in this position. The more removed you are from the ground, in rifle shooting, the more difficult it becomes. Prone, sitting, kneeling, and offhand, decrease in steadiness in regular

stages.

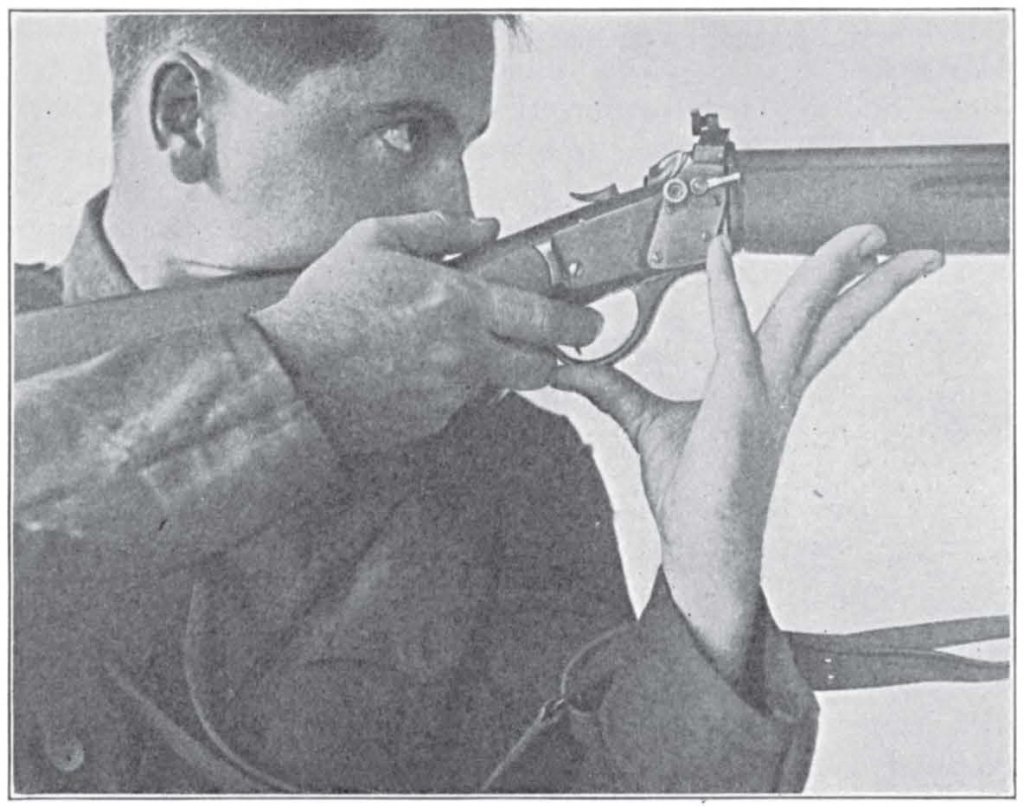

The first of the offhand positions is purely a target-shooting version. The palm-rest of the Free Rifle is merely an artificial aid to this first form, which is the hip- or body-rest.

In this, the rifle is held perched on thumb and fingers, thumb on guard, fingers about the end of the magazine floor-plate of the service rifle, elbow on hip, or pulled firmly against body, body facing at nearly right angles to the line of fire, head dropped forward into the line of sight.

Most men err in not turning the body far enough around from the line of fire, and get the elbow too much to the front.

The sling is of no aid in this position.

It is a poor one for use in a wind, and is not practical for game or war. It is, correctly enough, barred from the offhand stage of the National Matches as entirely artificial.

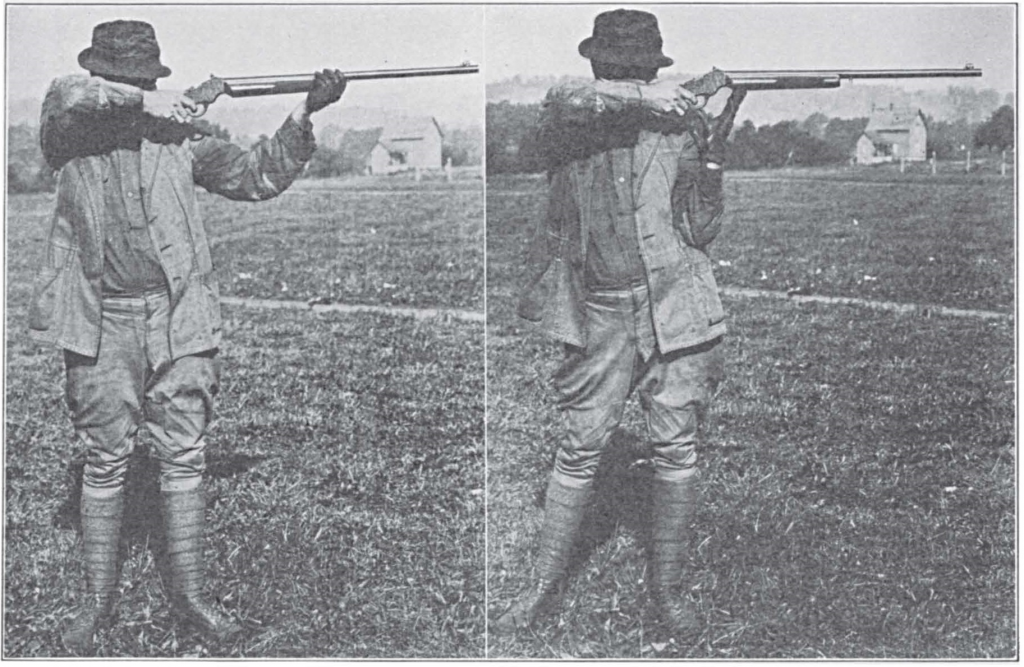

The other form is the extended arm—the shotgun, or deer shooter’s, position. It is divided, roughly, into half- or full-arm extension. The shooter will take the extension that seems the most steady. The heavier the rifle, to a certain degree, the steadier it will hold in this position; but this can easily be overdone. Light, muzzle-deficient rifles require the left hand run well out to control them.

The right hand should do most of the work, and pull the rifle firmly to the shoulder. The rifle should remain at the shoulder and be fairly steady, with the left hand released entirely. This depends much on the weight of the rifle, of course.

The left hand is the guiding hand and the steadying hand. You cannot get steadiness out of muscles on a strain, hence the desirability of letting the right hand do most of the work.

Left side well toward target, left elbow as far under rifle as possible with the build of the shooter. In a high wind, run left hand well out, and shoot the target “as it goes by.”

In any standing position, success is purely a matter of trigger control and touching it off at just the right moment, compounded with an ability to avoid jerking the trigger for a wide shot now and then.

CONCERNING TRIGGER CONTROL

The beginner must remember that, with the exception of prone, no rifle is ever held motionless, and the apparent lack of motion of the rifle of the old hand, is only apparent—the telescope shows that there is still a little wiggle.

Hence, in every position but prone, the rifleman can make good scores only by squeezing off the rifle when it is approximately correct in the alignment of front sight and mark. The farther from the ground the position, the wider will be the swings, and the less the front sight will hesitate under the mark.

Wherefore the festive beginner thinks that he can fool that rifle, and snatch the trigger off the instant the sight touches the mark. It looks reasonable, but the results are truly deplorable.

What happens is that, being a beginner, the shooter could not pull the trigger hurriedly in any event without moving the rifle. Second, the instant his brain signals FIRE! on the report of Chief Scout Right Eye that all is jake, all of his muscles tense up to help in the party. Third, there is a delay, even in the function of brain and muscles, and in the mean time the rifle swings off the mark.

The old-timer can make a rifle go at the approximate instant he desires by a little increase in the weight of squeeze, but keeping all the rest of his buttinski muscles out of the deal.

The tyro cannot, and his only salvation in any but the prone is merely this:

Relax all possible, take up the slack in the trigger, and let the front sight swing and gyrate as it will under the bull.

Keep increasing the squeeze little by little, trying to “think it off” as the front sight is about right under the bull. Often the shot will come when you are not quite expecting it—but you can “call” the location to yourself because of the mental picture you have of the location of front sight and mark as the shot cracks.

This “calling” business is the first sign of your progress or lack thereof.

If your shots, offhand, strike about where you had the picture of the front sight, you did your part of the squeeze and you are improving rapidly.

If they fail to land where you call them, either your front sight was moving too fast, or else you were jerking the trigger.

The good offhand shot makes his scores by some queer and unexplained ability to add just the trifle necessary to the squeeze at just the right time; he almost “thinks” the rifle off. It is acquired only by practice, and it is always done while the rifle is slowly swaying back and forth across the paper.

Don’t try to fool yourself or your rifle—you can’t yank a trigger fast enough. You cannot, even with a quadruple set trigger and a Martini action, the fastest way known to science to cause a bullet to emerge from a rifle barrel.

If you cannot “call” your shots, or if there is no clear mind-picture of front sight and position of bull in relation to it as the shot goes, then you are kidding yourself and making no progress.

No matter how wabbly you are, no matter how wide your swings, if you are squeezing the rifle off you can tell where the shot should strike.

The only time this may fail as to exact location is where you are conscious that the rifle was swinging rather rapidly as the shot went, and your shot is found wider in the same direction than you thought it would be. This is due to the delay, the lapse, in the ignition, and barrel time of the bullet. It is much less with very fast actions, like the Martini, and it is much more with slower actions, like some single-shot hammer types or fool bolt-action guns, with their cocking pieces loaded down with sights, and slower than cold honey.