The following information on schuetzen rifles and shooting comes from Rifles and Rifle Shooting by Charles Askins. Rifles & Rifle Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

Two hundred yard sharpshooting is one of the finest recreations connected with the use of a rifle, or for what matter any other tool. Our present off-hand sharpshooter combines the ethics of the old long rifleman of a former century with the ideals of the German or Swiss Schuetzenman.

The typical American rifleman of the past was a grim and quiet chap who shot close and said nothing; he had a deadly concentration that made him unrivaled in war, but he didn’t know how to play. The Schuetzenman loved the sport for its own sake. He took his family with him to the shooting park; he ate much, drank some, talked a plenty, laughed long and loud, and shot a heap whether he hit or not. Of the two classes, one was the better shot, the other the better sportsman.

Formerly the German and the American shot at different targets, on separate ranges. The native son used the Standard target, a freak offspring of the military, while the Schuetzenman had his own German ring target, man target, point target, and eagle target. The American would have preferred “string measure,” an exact value for every shot, had that been practicable, while the German was a great lover of chance and luck with a partiality for the eagle target in which a wooden bird was shot to pieces, the man fortunate enough to strike a certain piece being crowned “King.” He liked the man target, too, with its vertical lines in which a shot ten inches off might count as much as a dead center. The American’s standard of excellence was a long series of shots without a wild thrown bullet; the German gave his prize to the one who landed a single bullet in the center. One style of shooting eliminated the mediocre, the other encouraged the novice.

The arms used differed widely, too, at one time. The German clung to his great Schuetzen rifle with its hair trigger, set so light that an Irishman could start it with a cuss word, though it didn’t mind a Dutch oath. Besides he would tolerate no rule that barred his palm-rest, and long, heavy barrel; neither could be see more merit in the standard target than in his own Ring—in which at least he was right. On the contrary the American usually shot under the rules of the Massachusetts Rifle Association which forbade palm-rests, rifles of over ten pounds weight, or triggers with a minimum pull of less than three pounds. The idea of one rifleman was ultimately to use his skill in hunting and war, the other shot purely for sport and the making of record scores.

Gradually, through a process of evolution and elimination, the two classes have come together in the present generation. The German still uses his “lucky” targets, but no longer values very highly the records made upon them, while the American has discarded his ten pound, three pound pull gun for the Schuetzen rifle, recognizing the utility of the German appliances, palm-rests, set triggers, Schuetzen butt plates, cheek pieces, and has gone him one better by inventing muzzleloading barrels and insisting upon telescopic sights.

The old Schuetzenman, born across the water, loved his brass band, his marching and countermarching, his ribbons and decorations, his beer, and his much shoot and little hit. Not so his son who will be found in the quietest corner of the shooting stand, saying nothing and sawing wood, the finest off-hand sharpshooter in all the world. On the other hand the American youth has deserted his own ranges and gone to the German mostly because he appreciates the need of a social side to the game; the jollity and wholesome fun of the Schuetzenfest appeal to him. The result is a new generation of rifleman who shoot together in all amity and whose work is far superior to anything seen in the past.

Whatever the practical value to the hunter or the soldier of practicing sharpshooting under modern conditions, and I do not credit it with having much, the sport itself is worthy of all praise. Moreover as a training in self control, controlled muscles, and nerve education it is superior to any sport in the world.

The man who would participate in off-hand match shooting must first of all look to his rifle. The ordinary military, the sporting, or hunter’s weapon is quite useless. He must select a Schuetzen rifle and prepare to manipulate it Schuetzen fashion.

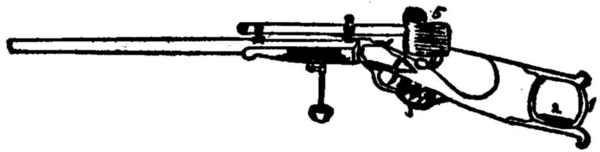

The most advanced type of the Schuetzen rifle is shown in cut published herewith. It has much to recommend it, yet a visit to the range will show that nearly every expert has modified and changed it to suit his own notions. Since, however, it would be impossible to describe at length all the variations that personal requirements demand I shall content myself by pointing out the features of the rifle illustrated which might be termed peculiarly Schuetzen.

The barrel is the Pope-Stevens with bullet seated from the muzzle as described under heading of Match Ammunition, Chapter VIII. The most desirable caliber is there mentioned also.

The sight should be the best telescopic match glass procurable, power from four to eight, micrometer adjusted for windage and elevation so as to give an inch to the line at two hundred yards. Whatever might have been true in the past, it is to-day impossible to compete successfully with peep and globe sights. Ignore spirit levels; the contrivance is useless in off-hand shooting.

Palm-Rest

The palm-rest is the Winchester, and is adjustable for length and angle without the use of tools; some prefer it fixed more toward the frame and others forward. The palm-rest is something that American riflemen once fought bitterly and consistently, rigidly barring it from their matches. Nevertheless they beat the devil around a stump by getting the effect of the palm-rest through balancing the rifle on the end of the thumb and the finger tips—some marksmen shoot in that position yet. This manner of holding is hard on the fingers when the piece is heavy, and otherwise is inferior to the handhold.

The palm-rest serves the double object of permitting the elbow to rest on the hip without unduly contorting the body, also preventing the hand from gripping the barrel which is inimical to evenness of elevation. It is difficult to grip a barrel with exactly the same force every time; the clasp of the hand may tighten or loosen and the contracting fingers of one hand have an effect on the other, causing irregularity of trigger pulling. All this, it might be noted, applies equally to other rifles as well as the Schuetzen, but a degree of accuracy which would be considered satisfactory with a hunting weapon would not rate as third class work with the match rifle. Delicately set Schuetzen triggers can only be used advantageously where the rifle is balanced rather than held, either on the finger tips or palm-rest.

The palm-rest is now in general use by American and German riflemen alike. The man who possessed none would be badly handicapped in a long series of shots, whatever his skill might be. It is not a handsome contrivance, but of its utility there can be no question; rifles weighing above fifteen pounds could hardly be shot effectively without it.

Cheekpiece for Telescope

The cheekpiece is also the Winchester; cut with especially high comb to adapt it to a telescope which is placed a full inch higher above the barrel than ordinary sights. It follows that where a glass is mounted an ordinary low comb and cheek will be practically useless padded up to the required height. A drop of an inch at comb will generally be found sufficient, but the slant to butt must be rapid, down to at least three inches; some prefer four. The cheekpiece, together with the blinder, affords a very secure rest for the head, and on its perfect fit largely depends the ease and security with which the rifleman holds his gun.

The Blinder

Generally speaking, the advice to shoot a rifle with both eyes open the same as when firing a shotgun is good. It applies especially, though, to game shooting, rapid firing, and where distance must be estimated at the time of taking aim. With the long, deliberate aim of the match shooter it has been found trying to concentrate the brain’s attention entirely upon what the sighting eye sees when both are open. On the other hand squinting one eye hurts the vision of the other, and this will not do. Hence we have the blinder.

This is a piece of moderately thick sole leather, fitted to the end of the ‘scope, then bent and shaped to curve around the head over the left eye. The blinder has three distinct purposes. It covers the left eye, obviating any necessity for squinting it, at the same time shutting off all side light either from the right or the left. It is fitted over the end of the ‘scope in such a manner as to act as a guard, preventing injury to the eye from recoil, and the heavy leather is an elegant head rest, firmly locking the head to the gun. As riflemen put it, a shooter crawls into his blinder and goes to sleep only to wake up with the crack of the gun and the marker signaling a 25.

The Schuetzen Lever

The Schuetzen lever is made in many styles with almost as many variations as there are individual marksmen. The author has designed one which he has found more satisfactory than anything at present furnished by the factories. The object of this lever is to place the fingers in such position that the forefinger will exert its pressure directly to the rear without any strain or tendency to press upward toward the thumb. Each finger has its own grooved rest in which it simply lies in a natural bend without any forced contraction or grip, which might involuntarily extend to the pulling finger, causing a premature let-off. When the fingers grip the stock, as in an ordinary rifle, it is almost impossible to manipulate the sensitive double trigger without an occasional accidental pull.

The spur lever is better than a pistol grip, but the middle finger which curves around it has a natural tendency to contract further until the tip of the finger rests on something; nothing is there to afford this rest and the consequent strain is communicated to the pulling finger. The whole idea of the “block lever” with finger grooves is to have the hand in a rest so natural and secure that the forefinger can lie against the most sensitive trigger without the marksman having a particle of fear of an involuntary pull, yet the finger will respond instantly to the will of the marksman.

Since half of off-hand shooting lies in correct trigger pulling, it follows that every contributing feature, including the triggers themselves, must be studied carefully. It is a universal complaint among riflemen that while they can hold well enough they cannot let-off. If a man could discharge his weapon by will power alone, our present rifle records would be discounted in a jiffy.

Fairly good double set triggers are furnished by the factories, but an expert gunsmith who makes a specialty of that sort of thing can improve them greatly. They should be adjusted to a very light pull, the greater the skill of the marksman the more delicate trigger he can handle. However, the trigger must never be so sensitive that it cannot be touched at all without yielding. I have seen more than one novice afraid of his trigger, making a little dab at it when ready to fire—needless to say he couldn’t shoot. The finest double set triggers that I have ever seen were those made by William Bauer of the Central Sharpshooters’ Association, St. Louis. No movement was perceptible to the eye when these triggers yielded to pressure.

Thumb Rest

A peculiar feature of the typical Schuetzen rifle is the thumb rest. Where to place the thumb when firing a rifle is always a problem. If placed on top of the tang it spreads the hand too much, causing an upward contraction of the forefinger in place of to the rear. To such an extent is this true that sometimes two ounces of force are necessary to pull the trigger where one ought to suffice. For this reason some place the thumb along the side of the grip in place of over it, but then it has nothing to rest upon. The problem has been solved by cutting a groove into the grip the size of the thumb, over which extends a steel plate. In this groove the thumb rests as securely as the fingers do in their place on the lever.

The Schuetzen Butt-Plate

The butt-plates that come on factory rifles have a variety of shapes, but those manufactured by private individuals differ still more. The Schuetzen rifle is not held like an ordinary weapon but is balanced. Without the Schuetzen butt there would be a tendency for it to lift away from the shoulder, a tendency that would have to be counteracted by a grip and rearward pressure—something to be avoided. Exacting riflemen have usually had butt-plates made to order, many having the lower arm long and upcurved back of the shoulder.

In off-hand rifle shooting with extended arm the right elbow is held rather high and would be under considerable strain if the aim were continued for any length of time. In deliberate Schuetzen work the arm is dropped until it rests against the butt, this both to hold the rifle in balance and to relieve the arm muscles of all unnecessary labor.

The most nearly perfect arm and shoulder support made is cast from solid brass, the back plate an inch and a half in width, broadening under the arm to two inches. This sort of butt-plate will so lock a man to his gun that a fifteen pound rifle will balance as though it had grown to him.

With a rifle of the sort described here, holding is simplified to training the leg muscles to support the body, second after second, without an iota of movement; to regulating the breathing, and to so distending the chest that the heart beating will not communicate its action to the rifle. Probably the leg training is the most difficult, and the majority would be able to hold steadier if permitted to place the left leg against a solid support.

Sharpshooting

Having our rifle, it only remains to practice—continual, never-ending, patient, persistent, studied practice. It is true that some men of strong nerves, good physique, and keen eyesight can develop rifle shooting skill more quickly than others, but it is no less true that the man who has made the greatest reputation as a sharpshooter is he who has worked the hardest for it. There is absolutely no exception to this and no royal road leads anywhere near success.

Probably the best scheme for the rifleman living in the city is to have two barrels for the rifle, one a .22 for the gallery and the other of larger bore for the range. Except in the matter of judging wind and light, gallery practice is almost as valuable as shooting the full distance. A certain number of shots should be fired daily, say with the .22 ten strings of ten shots to the score, all pulled with the utmost care. During his match shooting days the writer had a range of his own and made it a rule in good weather and bad to fire fifty shots every day at two hundred yards.

Take care to handle the rifle with machine-like, mechanical regularity. Place the feet exactly so every time, wear the same amount of clothing, fit the butt to its precise place on the shoulder, stand long enough to quiet the nerves and heart action, take a long breath or two, like a diver preparing to go under, and then settle the rifle to its aim. Find your steadiest method of swinging onto the bull and use that exclusively. Generally the rifle shots will be aligned above the bull, then the weight of the piece will settle it firmly into place, to swing gently back and forth across the target.

Along with muscle training will have to come nerve education. The great problem of rifle shooting is unity of action between brain and trigger finger. The student will soon discover that he can hold and hold, perhaps keeping the sights on the dead center for seconds at a time; he will pull and pull, but the trigger will not yield, though he knows a pressure of an ounce or two would start it. Of a sudden his sights begin to move off the mark and he tries to ease up on the trigger, when bang goes the gun—wild shot, of course.

What was he doing all the time he thought himself putting ample pressure on the trigger? He cannot tell, nor can anyone else more than conjecture. Perhaps he was really pressing the trigger but not quite hard enough; possibly he was pulling with the whole hand except the trigger finger, exerting all the force on the grip of the rifle; more likely he was not putting a grain of weight on the trigger, though his brain distinctly told him that he was. His “motor” nerves were locked rigidly by the effort of holding the rifle still, but the moment the piece moved the brakes were off and so was the shot.

The man who can pull trigger while his gun is hanging as though in a vise can shoot like a machine, but such an individual I have never seen. The shot must be pulled within the fraction of a second after the bead settles to the center or on go the “control brakes” and he will have to let the rifle move off to try again. No matter how well the shooter is holding, if he keeps on pressing after the trigger has refused to move at the dictate of his will, the first thing that must happen is the release of the nerves which control steadiness, and the rifle is bound to move before the trigger can be pulled.

Individuals differ, and the writer can best give his personal experience. In my shooting the pressure on the trigger was started just an instant before the sight covered the center, with the expectation that the trigger would yield at the precise time when the rifle settled “dead” in the middle of the bull. If my anticipations were realized I got a shot in the 24; if the trigger let go too soon, most likely the shot was as good as a 22, but if the trigger failed to release the lock on time, and getting impatient I forced the pulling to get value for a fine hold, the shot could not be called accurately and might go out of the bull. When anxious to make a fine score I never forced, but trying about three times for a perfectly timed let-off and failing, would then take the rifle down from the shoulder and rest.

I believe this is the common experience of trained sharpshooters, and the patience and forbearance with which they will try again and again for a pull-off is something remarkable. Naturally such extreme care would only be used in the last rounds of a good score when one badly held shot would render futile all the good ones preceding.

By way of proving this point and at the risk of being thought egotistical, I shall have to describe an incident of my own work. When shooting at the tournament of the Central Sharpshooter’s Association at St. Louis I had scored on the German Ring Target 24, 23, 23, and had one shot to fire. H. M. Pope, of Hartford, Conn., had already made 94 in his four shots, and in order to tie him I had to make a 24 while a 25 would win. For thirty minutes I tried to get a perfect pull, going back to the stand again and again before I got it, a 24 which tied for first. The man who won third, H. D. Schneidewind, of Belleville, Ills., told me that he spent an hour and a half pulling his last shot, but he finally got his 24.

Such extreme care as this is liable to defeat itself, through an accidental let-off or one of the many things that can happen and spoil a good score. With rifles cracking to right and left, and impatient marksmen behind awaiting their turn, withholding fire for a perfect pull is a nerve-racking business, but such is sharpshooting at a national tournament.

As in other rifle shooting a great deal of the training for holding and pulling can be accomplished at home in the room or yard without the use of ammunition. Put up a bull’s eye corresponding in size according to distance with the regulation bull. Place an empty shell in the gun and sight on this bull and pull, and keep it up until thoroughly tired—train in this way every day, as often as time permits.

In this way the rifleman can so train his muscles that his sights will never quite move off the bull in the wildest movement they make while he is trying to pull. Only when he can hold continually; on the black for seconds at a time can he consider himself a reliable shot, for it is to be expected that occasionally a shot will go when the sights are at their widest swing and if this is outside the bull, some of the bullets will miss it before a hundred are fired. The acme of skill is never to let a shot go outside the bull, and never let the sights swing out after the finger settles to the trigger.

The manner of bringing the sights onto the center is something for the individual rifleman to solve in his own way. The proverbial instruction is for the marksman to bring his piece up from beneath until the sights cover the bull and then press trigger. This will not do with a heavy Schuetzen rifle balanced on a palm-rest.

The tendency of the big weapon is to swing across the bull horizontally, back and forth. Some men of quick nerve action can pull as the rifle swings, without altogether stopping it, and get good results. Usually they press the trigger while the piece is moving from right to left since the rifle in its left swing hardens and sets the muscles, consequently traveling more slowly. Probably a better system of regulating the swing is to have the left extremity of the movement just reach the center where the weapon must “hang” for an instant before beginning the return to the right side.

In my case I found that my rifle had a pretty regular swing but not pendulum like. It moved off the center to the right, rose a trifle, and then settled down across the bull from two o’clock to six, where I endeavored to stop it and let off—failing to get the pull it would again move off to the right and around as before. If I was in my best form, and using telescope, the sight would never quite leave the twelve-inch. All my premature shots would be to the right and high, delayed let-offs low, and now and then the rifle jumped beyond control throwing the ball high and to the left. In sharpshooting it is a great and fascinating gamble as to what is going to happen when the marksman settles his rifle on the black, but when the perfect pulls come regularly he has a feeling of power the nearest to omnipotent ever vouchsafed to man.

After a little experience on the range the rifleman can begin calling his shots, telling where they went before the marker signals. The more expert the shooter the closer he can call. It is nothing uncommon for a skilled shot to “call” his bullet within an inch of where it has gone. To do this he must not only see where the sights were when he pulled, but must keep his eye on them and note where they jumped to with the recoil. If the rifle rises straight across the bull with its recoil the marksman can expect to find his bullet where he sighted it, but if it jumps out badly to either side expect a bad shot in that direction. It is much easier to call shots with a lightly charged, heavy barreled rifle than with one much influenced by recoil.

It will not do to strain the eye too much in sighting. Experience will teach the shooter that the greatest clearness of vision lasts for but a short time, and then it fades to return again—this happening in regular rotation. The pull-off must then be so timed as to take place when the vision is the clearest, if the shot is to be called accurately.

The training of muscle and nerve is as arduous in a crack rifleman as that of the finest juggler in the world—in fact of all human beings he has the most perfect muscle control. Not only from seeing, but from feeling and mental calculation he has the most delicate perception of the movements of his piece. To such stage of perfection is the training in feeling where his rifle is pointed carried that after placing it upon the bull he can tell exactly the spot his sights are covering without again looking at them. I have known a marksman to sight his rifle, then shut his eyes, pull the trigger to order, and get a bull’seye—sometimes. While holding and not looking, of course, he had a mental picture of where the sights were swinging every instant of the time.

A word on wind and light. An even wind blowing across the range and not too strong permits almost as fine shooting as a calm. However, when it has sufficient force to carry the ball quite out of the bull with windgauge at zero very fine scores should not be expected, but the marksman should be satisfied with a bullet that lands in the 22. There is no such thing as a wind of perfectly uniform velocity, but twelve inches of wind probably means anything from six inches to fifteen, neither will the most careful watching of flags avail much; beware of tinkering eternally with the windgauge, that is a fatal habit. Set it for about the average force and take what luck brings you.

Fishtail winds, that is those that vary from four o’clock around to eight are the most troublesome, and about all that can be done is to watch the flags and “hold for it” allowing the sight to remain at zero. Head winds, sweeping about from ten o’clock to two are also very vexatious, not only driving the bullet from side to side but down. Cuss the wind when it don’t behave, but keep on holding close and it will get the other fellow’s “goat” in place of yours.

Occasionally light will vary the elevation as much as six inches. An experienced marksman can usually give a pretty shrewd guess at the elevation before firing a shot, and a few “sighters” will tell him all he needs to know. As the sun descends usually the bullets will “drop” with it. If toward the finish of a good score the sun should become obscured by a passing cloud better wait till it clears before firing again.

The crack marksman must be of temperate habits. The man who smokes in order to keep his nerves steady will soon find himself betrayed by nervous irritability and the drinking man can only shoot well when braced up exactly so in which condition he finds it difficult to keep himself.

We might as well admit that success in match rifle work is entirely dependent on concentration of mind. Some men can concentrate powerfully but only for a very short time—they will make startlingly high scores but only now and then. Another will be able to keep to his knitting hour after hour, under any and all circumstances, and he is the man his club banks on in a match.

If ambitious to win and to break records, stuff cotton into your ears, smile when spoken to but never reply and never hear what is said. If the other end of the shooting house falls down and kills a man, never know it as long as your end is standing. Say nothing and saw wood, say nothing and saw wood; it is man killing work, but it gets results. WORK tells the whole story, for there is no fun about it, and it is not to be denied that concentration is the bane of all American sports.

The other way of match shooting is to take things as they come. Shoot only when you feel like it. Talk, listen, laugh, and watch the play. Rejoice with the man who made three reds in succession, and sympathize with the peppery old fellow that the dog-gone blinkity blanked marker is forever cheating by showing a ten where he held right for the dead center. Yes, the farce-comedy never was seen that could touch a German Schuetzenfest. But cheek by jowl with the fellowship and the humor comes the training that gives man dominion over the beasts of the field, makes his country impregnable, gives him a power of life and death only second to that of his Maker.

THE END