The following information on the development of the revolver comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

From the earliest times inventors have utilized the revolving barrel or chamber principle in order to effect a repeating firearm, but in nearly all cases the rotation of the fresh chamber or barrel was effected by hand rather than by the action of trigger or hammer.

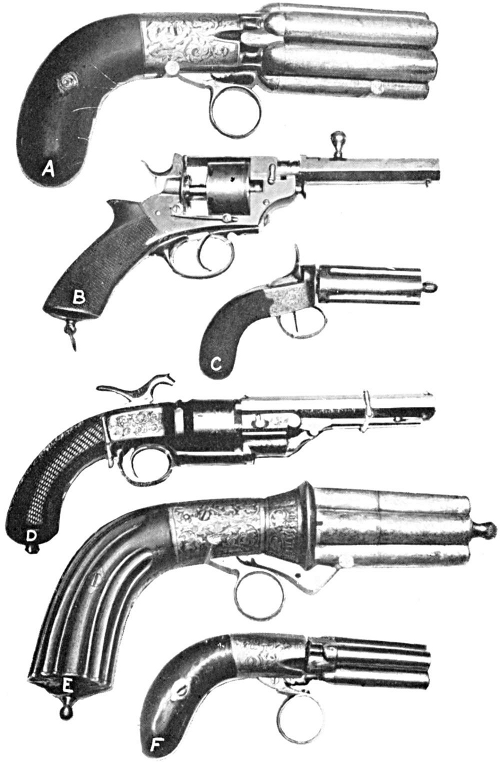

The first type of revolver, apart from museum specimens of great rarity, such as the flint-lock snaphaunce revolver in the United Service Museum, is the familiar “pepperbox,” a design of four or six barrels rotating around a central spindle, and fired by the blow of a hammer actuated by the trigger which also revolved the barrels in exactly the same manner as the modern double-action revolver. There were many makers of these, such as Allen and Thurber, Walker’s patent, and many English and Continental firms, and several types, some with hammers above and some with them below the barrels. Some models have separate barrels, but the majority are bored out of one solid piece. A notable variation is the “Comblain,” in which the barrels remain stationary while a revolving internal hammer strikes the caps.

In all these “pepperbox” revolvers the nipples were at right angles to the cylinder, and it was not until after Colonel Colt in 1835 patented his first revolver that centrally placed nipples were employed.

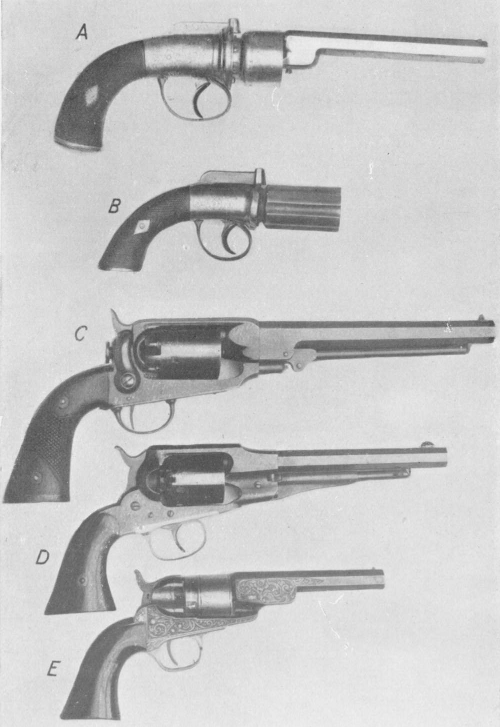

For a complete account of Samuel Colt and his extraordinarily successful career as an inventor and as a manufacturer, the reader is advised to turn to Sawyers’ excellent book, vol. ii., of “Firearms in American History,” which gives complete particulars, and traces the evolution of the Colt revolver through its chequered career, from the first model “Texas pistol” of 1835, through the Mexican War model of 1847 and the great lawsuits over patent rights, then through all subsequent models of revolvers up to 1865. The book is voluminous in detail, and all models are illustrated, as are many other types of American historical arms and revolvers.

The chief points about Colt’s patents were—First, rotating the cylinder by the act of cocking the hammer, so as to bring successive chambers in line with the barrel; second, locking the cylinder in the proper position during the moment of discharge, and unlocking it by lifting the hammer when cocking; third, that each nipple and its caps were isolated from the others by partitions on the cylinder, to prevent simultaneous discharge of two chambers by the flash of the cap. The London factory for Colt’s arms was opened in 1853, but only worked till 1855, when it was taken over by “The London Pistol Company,” and produced their replicas of “Colt” revolvers with the original machinery. The principal output of the London factory was the 1851 model Navy Pistol Colt revolver and the 1849 Pocket Pistol .31 and .34.

The number of Colt muzzle-loading revolvers of various types is legion, and they are mainly of interest to American collectors. Small details of size of trigger-guard, method of fastening the barrel, place of manufacture, etc., make considerable but fluctuating variations in their value, but Colt revolvers with secret triggers similar to the specimen in the United Service Museum, and models made at Paterson, N.J., are of considerable value.

The original and usual models are of .44, .36, or .31 calibre, and have cylinders engraved with “stage-coach hold-up” or naval scenes. They are single action, and have the barrel simply connected to the central spindle around which the cylinder rotates, without any top strap attaching it to the breech-block. Loading is effected by ramming a conical bullet with a varnished goldbeaters’ skin cartridge full of powder attached to its base into each chamber. This ramming, as is common with all muzzle-loading revolvers, is effected by means of a lever and plunger attached to the side of the barrel. Tight ramming was a necessity, inasmuch as the explosion of one chamber might fire another charge in the adjoining chamber if the loading had been with a loose ill-fitting bullet. The loaded chambers were then capped at the base, the cylinder being free to revolve when the hammer was at half-cock. Sighting was accomplished by means of a notch cut in the hammer, which, when raised, just intersected the line of sight. A contemporary opinion of the value of the new invention can be gleaned from Hans Bush’s “Rifleman’s Manual,” and there is no doubt but that he correctly represents the feeling of sportsmen of the period. He states:

“I may now briefly advert to the ‘repeating principle,’ as applied to firearms in general, but more especially to pistols and rifled carbines. It is to our Transatlantic friends that we are indebted for the perfection of these weapons, for though, more than two centuries ago, various attempts were made to produce a series of successive discharges from one arm without the necessity of reloading, it is to Colonel Colt’s perseverance, energy, and mechanical skill that the merit is due of having successfully vanquished all the difficulties that presented themselves in their construction.”

Innumerable were the objections he had to contend with at the outset. Many sneered at the idea as preposterous. “They would always be liable to get out of order.” “They would take too long to reload.” “They would, besides, always be missing fire,” etc.

As regards the liability of the revolving pistol to get out of order, this was satisfactorily disproved by a severe trial instituted by order of the Board of Ordnance of the United States, who directed a holster pistol to be discharged twelve hundred and a belt pistol fifteen hundred times, cleaning them but once a day; after which ordeal neither of the pistols appeared to be in the slightest degree injured.

With respect to the cost of production, as almost every part is formed by machinery, hand-labour being only required in the finishing department, Colonel Colt seems likely permanently to retain in his own hands the business which his ingenuity has created, for he will, of course, always be in a position to undersell any imitators that may appear. Great security is also obtained from the cause above stated, for we find that upon “proof” only one barrel and one cylinder burst out of 2,082. The most perfect uniformity of detail is attained from the mechanism employed for the several parts of each class of weapon being precisely similar; so that if any become damaged on service, a great number of available arms can be immediately compounded of those which have been partially injured.

The ramrod attached to these pistols consists of a very clever but simple compound lever, which forcing the ball effectually home, hermetically seals the chamber containing the powder, and by the application of a small quantity of wax to the nipple before capping, the pistol may be immersed for hours in water without the chance of a miss-fire.

The movements of the revolving chamber and hammer are ingeniously arranged and combined. The breech, containing six cylindrical cells for holding the powder and ball, moves one-sixth of a revolution at a time; it can only be fired when the chamber and the barrel are in direct line. The base of the cylindrical breech being cut externally into a circular ratchet of six teeth (the lever which moves the ratchet being attached to the hammer) as the hammer is raised in the act of cocking, the cylinder is made to revolve, and to revolve in one direction only. While the hammer is falling, the chamber is firmly held in its position by a lever fitted for the purpose; when the hammer is raised, the lever is removed, and the chamber released.

So long as the hammer remains at half-cock the chamber is free, and can be loaded at pleasure. The rapidity with which these arms can be loaded is one of their great recommendations, the powder being merely poured into each receptacle in succession and the balls then dropped in upon it, without any wadding, and driven home by the ramrod, which, of course, is never required to enter the barrel.

While carried in the pocket or belt there is no possibility of an accidental discharge of these pistols. Whenever it is required to clean the barrel and chamber, they can be taken to pieces in a moment, wiped out, oiled and replaced.

The hammer at full-cock forms the sight by which aim is taken. The pistol is readily cocked by the thumb of the right hand, a plan in every way far superior to the arrangement whereby the hammer is raised by a pull on the trigger. This is in every respect most objectionable, the pull materially interfering with the correctness of aim, and the scear-spring having the duty of the mainspring to perform as well, is apt constantly to be getting out of order. Not so Colonel Colt’s; as regards the purposes for which they are intended, they may be pronounced in every respect perfect.

The following testimony of Major Robert Bruce in favour of Colt’s revolvers is quoted from the report (1854) of the Select Commtitee on Small Arms. It proves sufficiently their value and efficacy. “I consider,” said that gallant officer; “Colt’s revolver very far superior to any other we saw at the Cape during the Kaffir War. That opinion is founded upon its accuracy, and in its not failing in what you require. I have never seen an accident with it, and I have never seen it, in discharging, become involved in any difficulty. I have seen it fall into the water and returned to its belt without being discharged, and afterwards, perhaps after the lapse of some days, I have seen it discharged most perfectly without the least failure of any one of the barrels. I have ridden hundreds of miles with a Colt’s revolver by my side, and always found that there was an impossibility of the powder shaking out. The lever ramrod forces down the ball in such a way that no other ramrod could do.” Much additional evidence was given to the same effect—in short, no valid objection can be raised against them.

His cavalry pistols are, in fact, pocket rifles. With one of them I once fired from a rest thirty-six rounds at the enormous range of four hundred and ten yards! Six bullets struck the butt at distances varying from thirty to thirty-six inches from the centre of the target, eighteen bullets struck within the circumference of a circle seven feet in diameter, and the other six shots at heights varying from ten to twelve feet above the target—satisfactorily proving the capacity of the weapon for still greater range.

It must be remembered that for this experiment I had no sights adjusted. The elevation was taken altogether by guess. I am convinced, however, that if requisite sights could be fitted one might insure fair shooting, even with these seven and a half inch barrels, at 500 yards.

The wound which a conical bullet from one of Colt’s revolvers inflicts is terrific, driving before it, as it does, a cylindrical plug of muscle or bone. The haemorrhage or shock to the system is so great that death in the majority of cases usually ensues. No one, indeed, who has not had some experience with these diminutive rifles can form any idea of their capabilities. But their reputation is now so thoroughly established that the inventor may feel secure against the many attempts that have been made to impugn their character.

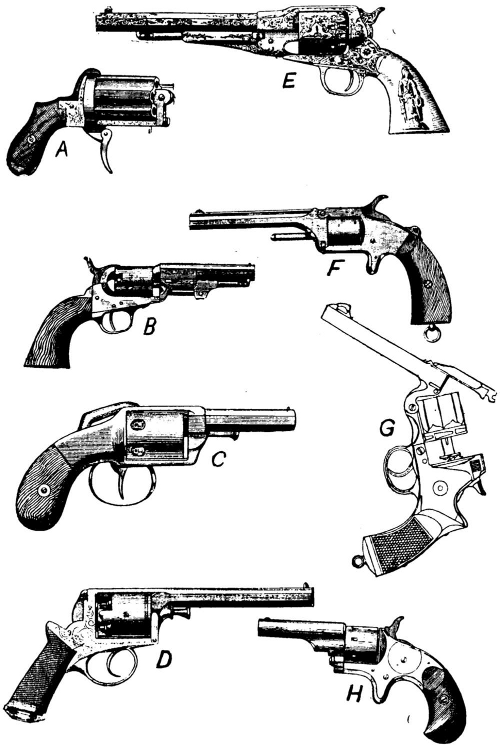

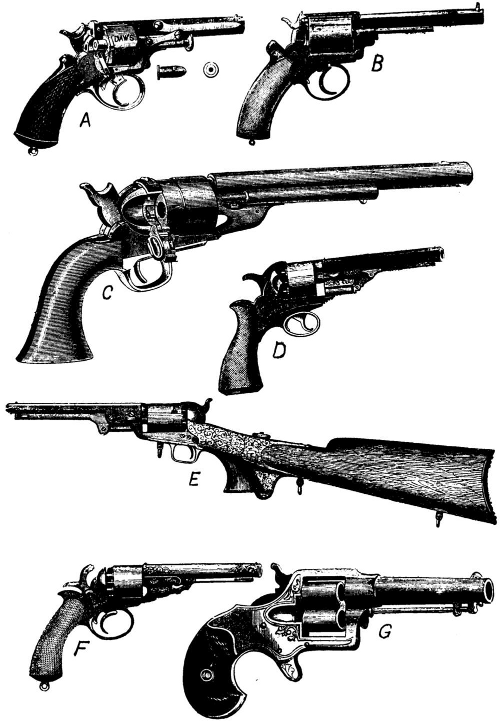

The success of Colonel Colt’s revolver stimulated numerous gunmakers and inventors to further efforts, among which were one or two makes, notably Cockran’s and Wilkinson’s, with chambers arranged like the spokes of a wheel, the cylinder being vertically pivoted. In the Wilkinson revolver the cylinder was removable for independent loading by lifting a top strap that held it in position, and the firing was effected by a long hammer similar to the pepperbox pattern overreaching the rear chambers. Similar pistols, but with the radial cylinder vertically pivoted, have also been manufactured; but the system was never popular or successful, probably because of the mechanical difficulties and the distinct objection of the ordinary man to employing a weapon in which, at least, one loaded chamber pointed directly at him. By 1853 design had steadied down to the solid-frame muzzle-loading revolver of Deane and Adams or Tranter pattern, and large numbers of these weapons were despatched to Australia and the various British Colonies then in process of exploitation. In America an enormous production of weapons was taking place, and the revolver has always been recognized as their national weapon. At the same time, inventors were attempting to embody the cartridge and cap in one, in order to perfect breech-loading mechanisms, and the result of this is an overlapping period of percussion arms of the plain muzzle-loading type. Weapons made breech-loading to take a separate cartridge, but fired by means of a cap placed upon the external nipple, self-igniting cartridges of the needle-gun type, and, finally, the development of the metallic cartridge in its first varieties as rim and pin-fire systems.

Among the notable muzzle-loading American pistols we find the Savage, a revolver operated by pulling back an under lever to cock the hammer and rotate the cylinder, a trigger connected with the lever being fired by pressure of the first finger, the lever itself being operated by pressure of the second. In this weapon the cylinder was held up against the base of the barrel by a method similar to the later invented Nagant.

The Starr revolver, which had a tip-up barrel secured by a pin fastening in the top of the breechblock, and which could be “broken” in order to remove the cylinder for loading or cleaning.

Allen and Wheel-lock revolvers with a side-action hammer striking tangentially set nipples, and a host of other makes, such as Remington’s, Whitney’s, Roger and Spencer’s, Springfield, etc., which in the main followed Colt’s design with the exception that most of them were solid framed—a top strap connecting the butt of the barrel with the top of the standing breech.

Metallic cartridges of the rim or pin-fire types made their first appearance about 1850, for at the Great Exhibition of 1851 we find the French gunmaker, Lefaucheux, who invented the pin-fire cartridge; Flobert, the inventor of the bulleted breech-cap and the father of the rim-fire system; Lancaster, with his central-fire cartridge, used in walking-stick guns to the present day, and the Continental needle-gun cartridges.

These needle-gun cartridges were the first type of self-igniting cartridge used in pistols, and consisted of a bullet having a cap or detonating pellet in its base; behind this was the powder charge, in a combustible linen or paper case, the base of which contained a wad pierced by a central hole and lightly covered with blue waterproofed paper. Ignition was effected by a hammer carrying a long pivoted needle, which struck through the base wad and powder charge, igniting the cap at the base of the bullet. The base wad was pushed forward by the next cartridge on entering the chamber.

A few Continental pistols for this type of cartridge, with a tube container above the barrel and a crude falling-block mechanism, are still extant, but the ammunition was dangerous, and the escape of gas at the breech alarmingly unsafe for a repeating mechanism.

The pin-fire cartridge is substantially the same as is used to this day in cheap Continental weapons, but was more dangerous and less reliable than the rim or central fire; it also suffered from the disadvantage of having to be placed in the chamber with the pin in its proper position projecting from the notch, and as this position in a revolver is of necessity vertical, the hammer and cocking-piece interfered with the sighting of the weapon.

The rim-fire cartridge originated from the development of the saloon or small-bore target pistol, and the author has been fortunate enough to collect at various periods, pieces showing the development of the idea.

The first step is the muzzle-loading .22 calibre weapon with a nippled breech, the action being opened to admit of the placing of a percussion-cap upon the nipple set in direct line with the axis of the bore. The second step is the substitution of a hinged anvil and extractor, thus making the piece entirely breech loading; while the third step is the plain, rimmed-bulleted breech-cap. This idea was readily seized upon by American inventors, and the evolution of the early Smith and Wesson revolvers of .22 calibre, the barrel hinging up from beneath, the Colt, Ballard, and Remington “Derringers,” the Sharps four-barrelled pistol, and kindred rim-fire pistols of American manufacture, was the direct outcome of the invention of bulleted breech-caps.

By 1860 breech-loading pocket weapons were popular, and small-calibre repeating mechanisms, such as the Remington repeating Derringer of .32 calibre, the Henry Volcanic pistol, which was the forerunner of the Winchester rifle, and a number of similar inventions, were in use. Breech-loading for the larger bores was not common at the period of the American Civil War, but came into fashion very shortly after.

The development of the Derringer from the large-bore conically rifled pocket muzzle-loader into the .41 rim-fire, single-shot, vest-pocket, self-defence pistol is peculiarly interesting. The first Colt Derringer has the same pivoted swing-over mechanism as was common in the first French saloon pistols of the same period. This first Colt Derringer (No. 1) was made in metal throughout, and pairs were issued for the use of Indian Civil servants. The weapon has an almost concealed hammer and a “knife blade” extractor to loosen the fired cartridge. The second Colt Derringer (No. 2) was similar, but had wooden stocks and a rather larger grip, while the third is the present-day model, with spring ejector and horizontally pivoted barrel. Among other American Derringer pistols were the Ballard, a tip-up weapon with a ratchet extractor similar to the one in early model Smith and Wesson Frontier revolvers and the double-barrelled Remington Derringer as used today. This weapon has an automatically movable striker on the hammer, which moves when the hammer is cocked, and strikes the rim of the cartridge in the upper and lower barrels alternately.

Derringer pistols were not built for accuracy at long ranges, but for close work over a table or shooting through the pocket. For this purpose of self-defence the heavy bore (.41) and powerful cartridge were eminently suitable. All these pistols and most American revolvers of the period were single action, and with the majority no trigger-guard was fitted, popular prejudice being distinctly against any unnecessary fitment that might delay one in an instant drawing of weapons to exchange shots.

The Sharps four-barrelled pistol was a popular model at this period, and was mostly made in .22 and .32 rim-fire calibres. A revolving nose upon the hammer caused the striker to fire the barrels in rotation, a device similar to that employed in the Comblain and Braendlin four-barrelled mitrailleuse pistols of later date.

The adaption of muzzle-loading revolvers to breech-loading systems brought out some queer devices, and in some cases merely the nipple breech of the cylinders was turned off, leaving the ratchet as a spindle projection. Around this boss was adapted a keyed ring fitted with strikers, which were hit by the hammer and fired the central-fire cartridges in the ordinary way without further alteration to the hammer or standing breech. Later models fitted a larger cylinder and a striker to the hammer. Pistols converted in this way are still in use in Mexico.

The Colt .45 Frontier six-shooter, of enormous fame, was the first and most celebrated of all central-fire breech-loading revolvers, and maintains its popularity as a reliable, accurate weapon to the present day.

The alteration from the muzzle-loading revolver was slight. The barrel and standing breech were connected by a top strap, or rather the barrel was screwed into a solid frame; the hammer was modified and equipped with a striker, and the loading lever gave place to an ejecting rod. Loading was accomplished through a gate at the right-hand side of the frame, and a notch upon the standing breech replaced the hammer backsight. The grip and balance of the weapon remained almost unaltered, though the single-action Bisley model .45 calibre Colt, with long handle and small hammer, was a distinct advance upon the original model.

Smith and Wesson, who had started to make breech-loading revolvers in 1859, next produced their celebrated self-ejecting models, the first patterns of which had ratchet ejectors and gracefully curved handles similar to the Colt grip. In later models this grip changed to the well-known Smith and Wesson shouldered handle, and the ejector assumed the present cam form similar to the Webley system.

These early weapons were all single action, but a demand arose for “self-cockers,” or double-action revolvers, and the Colt Frontier double-action and “Bull Dog” models met the demand. The Frontier types of pistol were usually chambered for the .45 Colt or the standard Winchester rifle cartridges of .44-40, .38-40, .32-20 calibres. This was to enable the frontiersman, cow-puncher, or miner, to use the same standard cartridge in either rifle or revolver. The “Bull Dog” models were chambered for the .41 long and short Colt’s central-fire, the .38 and .32 Colt cartridges, but single-action pocket revolvers, with solid frames and a pretty little seven-shot .22 calibre pistol, were also made to take rim-fire cartridges.

Other makers of this period were Smith and Wesson, Marlin, Merwin and Hulbert, Remington, Hopkins and Allen, and other arms companies too numerous to mention.

In England the solid-frame R.I.C. model Webley’s, Adams’, and Tranter’s, of similar pattern, developed on similar lines, the double-action revolver having always been more popular in this country than in the States.

In Europe the various countries evolved special military weapons, such as the French and German Ordnance revolvers, but it was not until 1890 that the self-extracting Mark I. Webley and its variations in smaller calibres were officially adopted.

Of all the pistols up to 1890 the Colt single-action Frontier was the most popular for general knock-about use. The Bisley model and the self-extracting Smith and Wesson were rivals for target shooting, while the English double-action military and constabulary revolvers were much more in favour than the American double-action models.

This period brings us to the last twenty years of pistol production, and closes the historical section of this book. The standard design of the modern revolver begins with the self-ejecting Webley models, continued into the modern solid-frame, swing-out types of Colt and Smith and Wesson, and eventually gives place to the automatic pistols now made by all three firms and many others.