The following information on duelling with pistols or revolvers comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

The practice of duelling with pistols developed out of the mixed type of mounted duel when the two combatants fought with all arms on horseback, as was customary in cavalry actions of the period. Such a combat was fought between Colonel Jonah Barrington and Mr. Gilbert in Ireland in 1759. The combat took place on horseback, the weapons being two horse-pistols loaded with ball and swan-drops, swords of the contemporary cutting type, and “skeenes”—long broad-bladed daggers. Colonel Barrington was shot in the face at the first encounter, but the large ball missed him, and the swan-drops merely broke the skin. He was ultimately victorious.

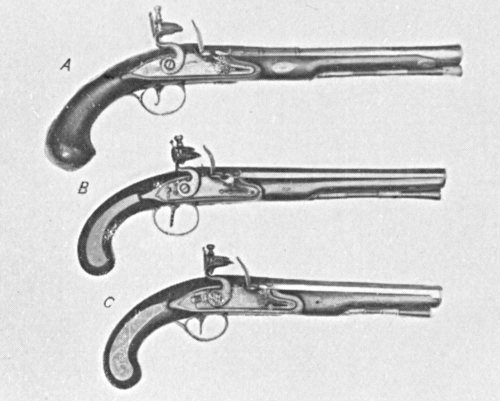

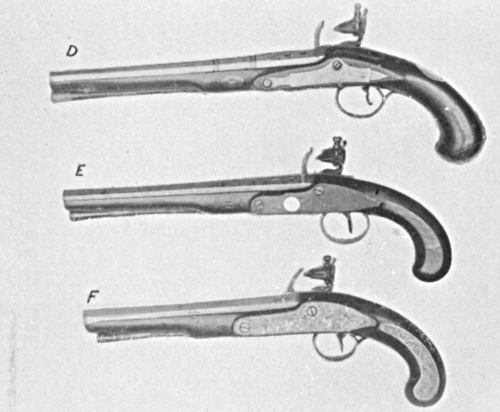

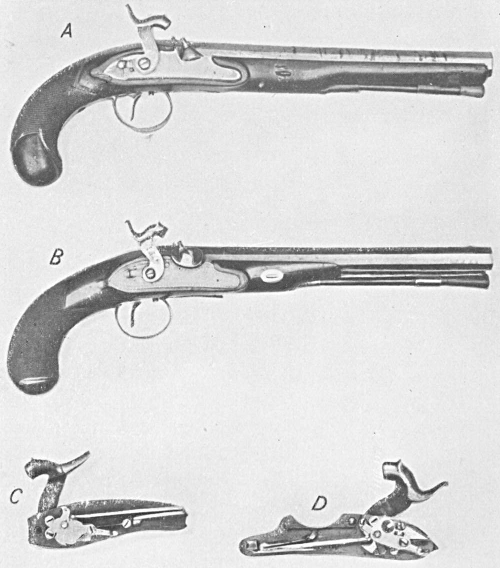

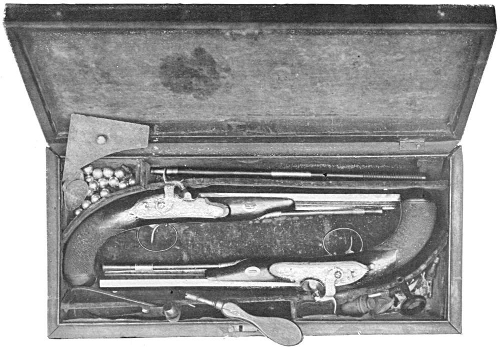

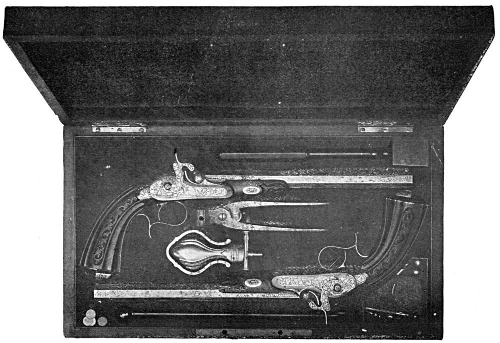

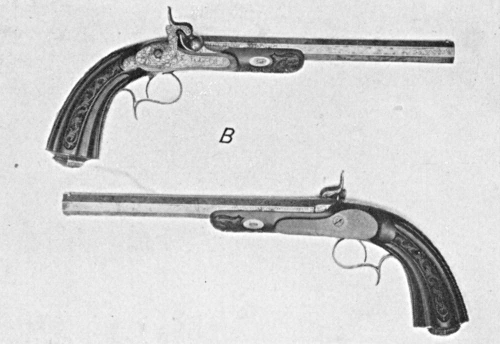

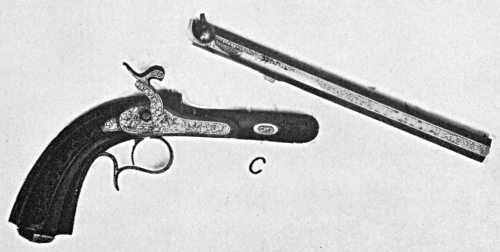

The latter half of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth were notorious for duels, Ireland being particularly ill-famed in this respect. At the period of 1870 no young Irish gentleman was considered a man until he had been “out” and “blazed” at least on one occasion. Duelling pistols were family heirlooms, and had special pet names, such as “Sweet Lips” and “Darling.” In 1777 the Irish “Code Duello,” upon which all English codes were founded, was formulated at the Clonmel Assizes, and adopted as the standard regulating affairs of honour. The usual pistol was a 9- or 10-inch barrelled smooth-bore weapon pistol, flint, and (later) percussion. Rifled pistols were regarded as bad form, and were barred by convention; but “semi-rifled”—that is to say, pistols with the breech-end of the barrel rifled to about half-way up—were occasionally· made and employed.

Duelling was popular with all classes—gentry and professional. In the Army it was so rife that it was partly checked in 1792, and forbidden on pain of cashiering in 1842. Among notable pistol duels, one of the first is that between Lady de Nestle and the Countess of Polignac in 1721. Later affairs of note were John Wilkes and Lord Talbot in 1761; Earl Bellamont and Lord Townsend at Marylebone in 1773. Duels in the dark were not at all unusual, one of the most notable meetings being that of Henry Gratton and Isaac Cory, both members of the Irish Parliament.

The clergy were not exempt from the practice, and in 1764 the Rev. Thomas Hill was called out by Cornet Gardner, of the Carabineers, for “ungentlemanly conduct,” and killed. The Rev. Henry Bate, of Ely Cathedral, who died in 1824, fought many duels (mostly about ladies and actresses), and killed three men.

Journalists were exceedingly liable to be called out; and even to this day duels between Continental editors and offended public characters are frequent, though often not severe. In 1821 Mr. Scott, editor of the London Magazine, was fatally wounded in a duel in the dark at Chalk Farm, his opponent being a barrister named Christie; and in 1835 Mr. Black, of the Morning Chronicle, and Roebuck, M.P., exchanged shots.

In the United States duelling was equally rife, but the “Code Duello” was slackly administered; most unusual and diverse weapons being used. A wide and disreputable latitude of conduct was permitted and condoned by popular opinion, so that the margin between homicide and duel was exceedingly confused.

During the Tripoli affair and at Gibraltar in 1819 duelling between American and English officers was common; and after Waterloo, the daily spitting, or embrochement, in duels of our young Englishmen by the enraged French was a scandal, only put down by the British insisting upon pistols, a weapon in whose use they excelled the French as much as the latter excel1ed them with the smallsword. As the French were the aggressors, and choice of arms devolved upon the challenged, this arrangement was quite fair.

The three most important duels in the States were those between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in 1804, Stephen Decatur and James Burrows in 1820, and D. C. Broderick and David S. Terry in 1859. The political issues affected by the fatal results of these duels in every case reflected upon the history of the nation.

The celebrated Bowie duel, which gave the name to the Bowie knife, was a mixed pistol, knife, and sword-stick affair, with several participants, and occurred in August, 1827.

American editors had to be good shots; and a famous affair took place between R. F. Beine, of the Richmond State, and W. C. Elam, of the Wing, as late as 1883.

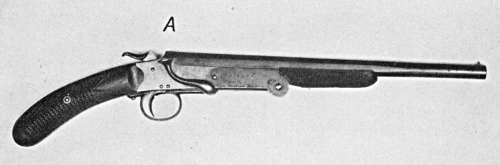

The short-barrelled Derringer was a favourite weapon, and was used at short range over a table between the combatants. Such a duel was fought between a doctor and General Bankhead Magruder in 1852. American ladies also had their affairs, and a duel between two of them at Buffalo, New York, both using “Allen’s Revolvers,” was stopped by the arrest of the combatants.

The decline of duelling set in about 1840; but in a book by Major Ben. C. Truman, of 1884, we read: “At the present time duelling is at a great discount in Ireland, and the laws against the custom rigidly enforced.”

Andrew Steinmetz, who wrote in 1868 a large treatise on the subject, deals with duelling as a modern affair, and one still practised. There was a curious terminology applied: “Leeching” was the duelling term for taking up one’s firing position. To “delope” was to fire in the air; while the meeting-place was termed the “releager.” Gentlemen perfecting their education or likely to have an affair of honour went through a severe course of training. Practice was made at small white wafers about two inches in diameter pasted on a black background, and the novice was advised to “culp,” or break, three dozen of these each morning before breakfast. When he could be sure of breaking twelve of these at fourteen yards in six minutes, he himself reloading his pistol between each discharge, he could consider himself trained.

A duellist about to fight was enjoined to retire early to bed, be called at five and take a strong cup of coffee and a biscuit, to wash the eyes in cold water, and not to wear flannel underclothes. This latter because of the danger of flannel entering the wound with the ball. To steady his nerves he may smoke a cigar, and if faint take a small brandy with effervescent soda-water on his way to the releager.

The actual duelling position varied, as there were several systems. A “volonté à marche interromper,” “à ligne parallère,” being systems in which the combatants advanced towards one another, exchanging shots according to a prearranged code.

“Au signal” was the usual straightforward method of firing on the word of command, and “à barrière” the equally popular method of placing the combatants back to back, whence at a word they marched ten paces forward, turned round and fired.

In the usual “au signal” duel the adversaries were placed facing one another, and either both fired at the word of command, or it was decided by a tossed coin or the Code Duello which fired first. In no case were they allowed to take dead aim at one another before the word to fire was given, but each had to hold his pistol pointing to the ground behind his back, or erect armed, pointing to the sky. Ten, twelve, or fourteen paces were the usual distances.

The duel “à l’outrance” was the only exception to the above rules. In this the combatants each held one end of a handkerchief, and presented weapons at each other’s breasts before the word was given. Only one pistol was loaded, selection being made by lot; the winner having the choice of taking whichever weapon he pleased, both being covered by a handkerchief.

The duelling of the old days was covered by a strict code, but it was customary to bring your own pistols, whereas, nowadays, new pistols unknown to the combatants are insisted upon. Possibly the best accounts of duels are those given in fiction by authors who lived during the duelling period. A man of that time writing a book would of necessity be accurate in his description of the details and mode of procedure.

Samuel Lover in “Handy Andy,” 1842, gives an account of Irish contemporary life during the period 1820-1840, and the duels therein are fought with flint-locks; the combatants bringing their own weapons to the ground, the seconds loading for them, and both combatants “blazing” at the word of command.

The custom of duelling is now happily almost extinct, for it was a bad custom, and did more harm than good. It is often urged that there are cases when duelling offers the only decent way to settle an affair or punish a gross offence. There is much to be said for this point of view, but it was this same view-point, carried to impossible extremes, that forced public opinion into legislation which classes duelling with murder.

If one could trust that the Code Duello would only be appealed to in certain extreme cases, it would be an excellent antiseptic against certain conditions of our social development. Nowadays one is no longer obliged to hazard one’s life “in honour bound” over some trivial matter, but during the duelling period one was at the mercy of fools and perforce had to be shot at over trivialities.

To carry a challenge is now a severe offence against this country’s laws—to accept one even graver. Participation in an affair of honour would insure any officer’s dismissal from His Majesty’s Service, and to all intents duelling among British folk is obsolete.

Duels are still permissible on the Continent, and are not quite the bloodless affairs they are thought to be by the public.

Sword duels with the “épee de combat” are not as a rule serious, each opponent trying to pink the other in the forearm. Duels with sabres are much more serious, and duels with pistols the most serious of all.

In good class European circles it is now a rule that duels must be conducted as privately and with as little self-advertisement as possible, and the affairs are usually regulated by a Court of Honour that does its best to bring about a reconciliation between the parties.

Assuming that an honourable settlement is impossible, the seconds, two friends to each combatant, arrange the place and time of meeting. A case of new regulation pistols are bought at a suitable gunmaker’s, loaded in the shop, and the case sealed to prevent tampering with the load or practice with the weapons.

The usual distance is 25 metres, and choice of position for their men is settled among the seconds by drawing lots, as one place may have an advantage in light or wind.

The duel is conducted by a gentleman who is not a second: “M. le Directeur du Combat.” He opens the pistol-case, and withdrawing the weapons, offers the choice of the pair to the combatant who has drawn the winning lot. The other weapon is handed to his opponent.

They take their places, and at command cock their pistols.

The director stands back from the combatants about midway, and gives the command just as in the wax-bullet practice:

“Attention!—Feu! Un!—Deux!—Trois!”

The combatants must raise their pistols and fire after the word “feu,” and before the word “trois” is finished.

The Court of Honour, who regulate the affair, often see that the words of command are given very quickly, in order to disconcert and hurry the duellists as much as possible. The normal rate is at a hundred words to the minute, but it can be said infinitely faster.

If both miss, and one or other desires a second shot, they change places; the weapons are reloaded, and further shots exchanged.

Under this system there is little time for “deloping”—i.e., firing in the air, but the same condition can be intimated by placing one’s pistol behind one’s back on the word “feu.”

Modern duels in which one or both of the combatants are English do occasionally take place, and are always fought on foreign soil. To avoid all legal risk the challenge and its acceptance should also take place abroad, for it is not enough that the duel alone is fought abroad if the affair was started on British soil.

In any case the duel must be carried out under the existing rules of the country in which it is fought; and the use of other weapons or any informality of procedure would render all parties liable to arrest and punishment.