The following information on history, wars, and the pistol comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

“Mrs. Page. Alas, three of Master Ford’s brothers watch the door with pistols, that none may issue forth.”

—The Merry Wives of Windsor.

The English Chronicles tell us that when Edward IV. landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire, 1471, he brought three hundred Flemings armed with “hand gonnes,” but it is probable that these were hand cannon, or guns, rather than anything of a pistol type.

Henry VIII.’s reign sees the first introduction of the wheel-lock dag, or pistol, somewhere about 1530, as an official English weapon, but it is more than probable that match-lock pistols accompanied the discoverers of America—Columbus in 1492, Cabot in 1497—and were in use during the European wars of 1500-1557.

At this period of history the Protestant Reformation and the divided state of the rich and artistically advanced Italy produced a continual state of European warfare. Francis I. of France was crushed by the Duke of Bourbon and Charles V. of Spain at the Battle of Pavia, 1525, contemporary pictures of which show powder-flasks and match-locks; and the succeeding period up to 1560 was one of continual warfare, during which firearms slowly replaced the pike and halberd, until a sixteenth-century army mustered a large proportion of musketeers, arquebusiers, and cavalry—the latter armed with primitive pistols. The mercenary German reiters used the pistol as a cavalry weapon, and spread its use throughout Europe.

In the reign of Elizabeth (1558 to 1603), Drake, Hawkins, and Raleigh waged war with Spain, and the pistol or petronel, as a convenient weapon for shipboard use, was already popular at the period of the Armada, 1588; while in 1584 William of Orange—William the Silent—was assassinated by means of a pistol shot fired by Balthazar Gerard.

Elizabeth encouraged the London gunmakers, and during her reign the number of gunsmiths increased largely, but during that of her successor, James I. (1603-1625), the trade fell into disuse till there were only five makers left in London.

The Gunpowder Plot conspirators, in 1605, fled after the failure of their plot to Holbeach in Lincolnshire, where they used pistols in their attempt to resist capture.

In France the wars of Henry of Navarre and the Holy League ravaged the country. The French cavalry, composed of troops of gentlemen, had adopted pistols at the time of the Battle of Ivry in 1590. At the Battle of Longside, in 1568, we get from a contemporary writer (Sir James Melville) a description that shows that the pistol was still used as a missile. “The long pikes” of Queen Mary’s men “were so thick fixed in the others’ jacks that the pistols and great staves thrown by them which were behind could be seen lying on the crossed weapons.” The final combination of Henry III. of France and Henry of Navarre against the League, and the assassination of the former and the crowning of the latter Henry IV. in 1598 put an end to the civil war, during which the pistol was a recognized nobleman’s weapon and a favourite arm for assassins.

In 1618 the Thirty Years’ War broke out in Germany, and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, Wallenstein, and Tilly became the military leaders of the age. Gustavus Adolphus recognized the value of firearms and their great mobility, and under him the cavalry—supported by field artillery—were regularly equipped with a pair of pistols, a procedure that was followed by all European military commanders. His death at the Battle of Lützen in 1632 was attributed to a pistol bullet.

A “Military Treatise” written in 1619 gives some idea of the common firearm of the period:

“Hee that lovyth the saftie of his owne person, and delights in the goodnesse and bewtie of a peece, let him alway make choice of one that is double breeched, and if it be possible, a myllan peece, for they be of tough and perfecte temper, light, square, and bigge of breech, and very strong where the powder doth lie, and where the violent force of the fire doth consist, and notwithstanding trimne at the ende. Our English peeces approache very nighe unto them in goodnesse and bewty, (theyr heavinesse only excepted) so that they be made on purpose,”—i.e., specially ordered—”and not one of those common sale peeces with round barrels, whereunto a beaten soldier will have great respect, and rather choose to pay double money for a good peece, than to spare his purse and endanger himselfe.”

When Charles I. of England ascended the throne in 1625, he found the gun trade in a bad state, and forthwith issued orders in 1632 that a stated scale of charges for weapons should be drawn up. Under this we find that—

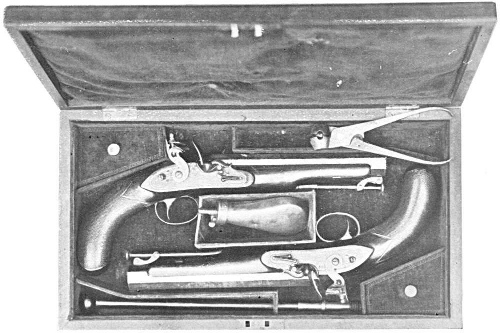

For a pair of fire-lock pistols furnished with a key (i.e., wheel-locks), mould, powder-flask, worm, scourer, in cases of leather and of length and bore according to the allowance according to the Council of War…£iii 0 0

For a pair of horseman’s pistols furnished with snaphaunces and similar equipment to the above…£ii 0 0

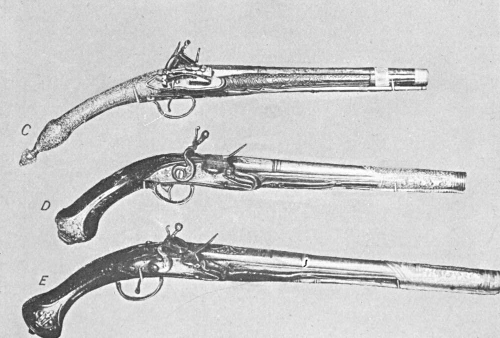

The Civil War of 1642-1648 was remarkable for cavalry work, and the pistols in use were principally wheel-locks and a sprinkling of snaphaunces. Nye, the gunner of Worcester(1649-60), and Henry Radoe, of Norwich, were both acquainted with the snaphaunce; the latter as early as 1585. In 1643 John Hampden was mortally wounded by a pistol bullet at Chalgrove Field during a cavalry skirmish, and Cromwell’s regiment of Ironsides were armed with pistols. In Scotland the all-steel Scotch dag was in favour, and was very popular as an officer’s pistol with the Cavaliers. The Scotch all-metal Highland pistol was a distinct type of flint-lock; yet its development undoubtedly bears traces of the influence of the excellent French pistolets of the period.

A very complete monograph and dated list of the best makers and marks is in existence, and a copy (in French) can be seen at the library of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The village of Doune was a notable centre for armourers and a place of frequent cattle fairs, where the clansmen could exchange their cattle for goods.

The art of making these special pistols was introduced there about 1646 by Thomas Caddell, who left the trade to his children and apprentices.

A regular guild of pistol-makers sprung up there, and a large export trade was initiated, the Doune pistols being particularly appreciated in France and Germany, where half-armour still continued in use, the all-steel finish of the pieces blending well with the armour.

Among many of the best armourers of Doune were Caddell, James Sutherland, Michie, S. Micine, John Campbell, S. Stuart, Thomas Murdoch, John Murdoch, and David McKenzie. The trade did not die out till the beginning of the nineteenth century, and continued into the period of percussion-locks.

In 1798 Thomas Murdoch was the leader of the trade, and his prices varied from four to twenty-four guineas. The earlier types of Scotch pistol can be distinguished by their possessing a half-cock plate projecting from the lock in a manner similar to the release of a Spanish or Oriental lock.

The full-cock is, however, similar to the ordinary flint-lock, and cut on the tumbler inside the lock-plate. A very large bore wheel-lock dag for throwing hand grenades was used by some troops at the siege of Oxford.

After the Civil War many Cavaliers and Puritans emigrated to the newly founded colonies in America and the West Indies, and the pistol was a recognized naval side-arm during the Dutch Wars of 1652.

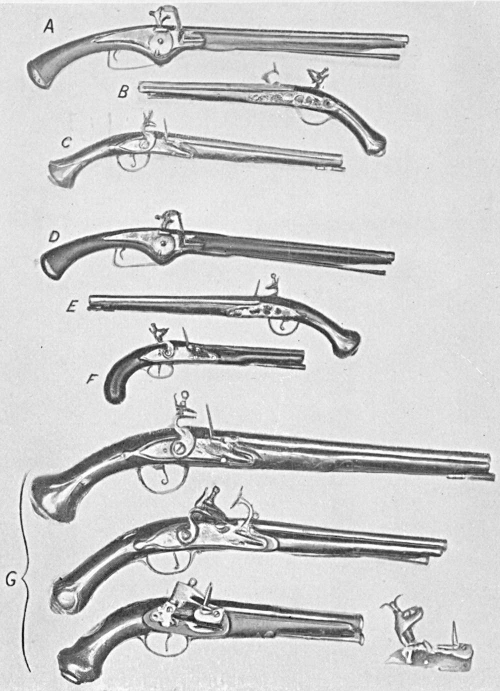

The restoration of Charles II. in 1660 saw the wheel-lock superseded by the true flint-lock, with which all of General Monck’s battalions were armed, although on the Continent wheel-locks were still made in Germany and Italy.

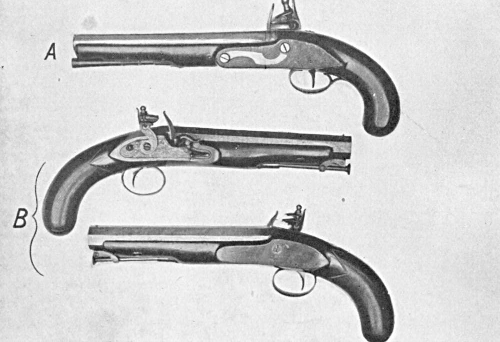

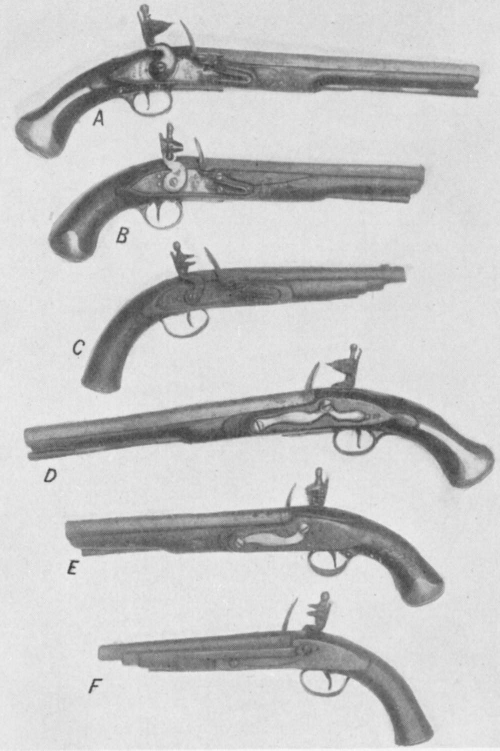

James II. acceded in 1685 and was deposed in 1688. During the Monmouth rebellion in 1685 the rebels had a mixture of weapons, but the royal troops were well armed, the long flint-lock pistol of sixteen inches having superseded the long, two-foot wheel-lock or snaphaunce as an officer’s weapon.

On the Continent flint-lock and snaphaunce pistols were adopted earlier, and at the siege of La Rochelle in 1628, under Louis XIII. and Cardinal Richelieu, the snaphaunce was in use.

By 1642 Louis XIV. and Cardinal Mazarin were the effective combination that steered France to a position of pre-eminence among the nations, and the style and decoration of French weapons of the Louis XIV. period is excellent, so good, indeed, that the same art was often applied to weapons of much later date and to English-made pistols by foreign artificers.

The accession of William of Orange (William III. of England) in 1689 was the prelude to a reign of warfare and rebellion. Scotland and Ireland were aflame with Jacobite sympathy, and the French under Louis XIV. assisted them with arms. In 1701 the Grand Alliance of England, Holland, Germany, Portugal, and Savoy was formed to prevent the union of France and Spain, and to preserve the balance of power. During this time flint and match-lock muskets were in use, but the design of the pistol progressed. The ensuing war of the Spanish Succession broke out under Anne, who acceded to the throne in 1702. By this time short-barrelled pocket pistols to fit the great “salt-box” pockets of the William and Mary and Anne costumes were common, and the large-sized, cannon-barrel, side-lock pistol was a favourite military officer’s arm.

The war with the Battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, and Malplaquet lasted from 1704 to 1709, and although military model pistols had settled down to the standard “Tower-lock Queen Anne” weapon, other patterns of Continental make were in use in the army, while the navy had a very mixed equipment of all kinds of pistols of varying bores.

George I. (1714-1727) had merely the Jacobite rising of 1715 and the siege of Gibraltar by the Spaniards in 1727, and the death of Louis XIV. in 1715 removed a menace to the peace of Europe.

George II. (1727-1760) had the rising of 1745; the War of the Austrian Succession, 1740-1745; and beginning of the Seven Years’ War in 1756; and the campaigns against the French in India (1756) and Canada (1756) with Wolfe’s capture of Quebec in 1759. The pistols of this period do not vary much, the same range of military, pocket, and holster pistols being popular; but as the century advanced the manufacture became more solid, the military affairs calling for good, reliable weapons. The American Colonies were largely supplied by English makers, but in 1740-50 commenced the manufacture of firearms on their own.

The reign of George III. (1760-1820) saw the culminating splendour of the flint-lock period, and the beginning of the percussion era, and it was during this reign that English gunsmiths attained world-wide celebrity for the excellence of their weapons.

The distinguishing factor of this reign was the loss of the American Colonies and their War of Independence, 1775-1783. The first shot in this war was the one that provoked the skirmish at Lexington, and it was fired by Major Pitcairn, from a Scotch all-metal pistol.

The Georgian military pistols are clumsy weapons of about fifteen inches long, locks stamped with “Tower” crown, G.R. and Broad Arrow. Their barrels are merely pinned to the stocks, while those French and Continental pistols of similar type are usually surrounded by brass or iron bands.

The French and Spanish allied themselves with the Americans, and naval conflicts in the West Indian waters and the sieges of Brest and Gibraltar further developed the trade in firearms, both military models and improved private designs being modelled upon the popular duelling pistol.

The French Revolution in 1789, with the execution of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette in 1793, together with the early Napoleonic Wars beginning 1796, and marked by Nelson’s victory of Trafalgar in 1505 and terminated at Waterloo in 1815, brought a great many French weapons to this country, while the campaigns in the Peninsula (1808-1813) under Wellington, account for many Spanish specimens. The notable pistol of this era was the British duelling pistol and the holster and military officers’ weapons made upon the same pattern. It is curious that the Duke of Wellington never possessed a pair of duelling pistols, and when called out ,by Lord Winchilsea in 1829 had to borrow a case from Doctor Hume, his attendant.

George IV. (1820-1830) and William IV. (1830-1837) usher in a period of development of the percussion system, and the birth of the revolver, while Queen Victoria (1837-1901) oversees the whole period of breech loading and the invention of smokeless powder. Automatic pistols belong to the last year of her reign, though their first real development is confined to that of her successor, Edward VII. (1901-1910), and their adoption into the Navy as a regulation pistol to the reign of George V.

Duelling continued till 1844 in England, and is still legal, though discountenanced, in France and Germany.

With the abolition of duelling, English makers ceased to manufacture the noted duelling pistol, and by 1865 the breech-loading revolver had taken place of all single-shot weapons, except a few target and saloon pistols made principally by Tranter of Birmingham.

The preceding precis of dates and battles, when compared with the types of pistol shown in the various plates, helps to fix one’s idea of their period and the slow advance of the importance of the pistol as a military or naval weapon. Up to 1775, the weapon was not accurate even at short ranges, but the later duelling and similar models were sure of a two-inch bull at twenty paces. The usual duelling distance was ten, and military pistols were really for use at point-blank range. The development of the revolver as a war weapon was due to the American-Mexican War of 1846, and to a certain extent to their war against the Seminole Indians in Florida in 1835, where the repeating system struck fear into the hearts of the Indians, used only to single-loaders. The celebrated Texas Rangers, who kept the Mexicans in order and freed Texas from Mexican rule in 1836, were all equipped with revolvers, and the name “Tejano” is a synonym in Mexico to this day for any good revolver shot. In the Mexican War later on, in 1846, all officers and many men carried Colts, and at close-range fighting, such as the Mexican then preferred, the weapon proved marvellously efficient. The discovery of gold in Western America and Australia in 1848 and 1849 spread the private use of the revolver, and the American Civil War in 1861-65 saw both sides revolver-armed. Some troops, notably Mosby’s Guerillas, were armed only with revolvers, two on the belt and two in the saddle holsters, and proved extraordinarily fatal in cavalry conflicts.

The officers bound to the Crimea in 1854 were all revolver-armed, though the cavalry pistol was the same old flint-lock of Georgian times. The Indian Mutiny (1857) was well in the percussion period, though by 1867 (the Abyssinian Campaign) and 1882 (the bombardment of Alexandria) breech-loading revolvers were fully established.

In Europe no serious attempt has ever been made to teach the use of the revolver as a cavalry weapon, except among the Austrian cavalry who were armed with the Werndl pistol. It is still, as in the days of the Crimea, purely an officer’s arm, or issued to small details such as despatch riders on special work. The reason for this is probably the prejudice with which the theory-trained European and British officer regards a revolver. Beyond firing the compulsory minimum course of so many rounds per year, they take, as a whole, no keen interest in pistols, and the advantages of the weapon for close work are completely ignored. Possibly they believe that the days of shock tactics for cavalry are over, and that horses are soon bound to be obsolete for European warfare. Even so, and admitting the necessity of mounted infantry work on the part of cavalry, in addition to their usual use, the revolver as a weapon in a skirmish is far better than sword or lance, and as a side-arm in addition to the bayonet for cyclist battalions, the need is obvious, for your military cyclist is at present unarmed when mounted, and merely equipped as an infantry-man with rifle and bayonet attached; while on his machine he must dismount, and is forced either to take cover and fight as an infantryman or fly defenceless with the lance or sabre of his pursuer at his back.

The revolver would give him at least a sporting chance in hedgerow fighting, and the present cyclist battalions might well be armed with the Webley’s revolvers withdrawn from the Navy on the issue of the present automatic pistol—certainly it would cost the nation no more, and would be better than merely storing them or breaking them up.

The United States of America Army and Navy both have pistols as the official side-arm, and in Cuba and the Philippines the revolver proved its excellence as a military weapon.

Europe, in her blindness, is as ever well behind the times.

AUTHOR’S NOTE.—Since the preceding paragraphs were written, the European War has brought the revolver once more into prominence, and the military authorities are again learning its value. I am glad to say that a better course of training is now insisted upon, and, though much still remains to be done, there are signs that the authorities are waking up.