The following information comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

From the earliest period of the invention of firearms, mankind has desired a short, easily portable, and easily concealed means of defence, and to this common desire we owe the pistol, the revolver, the “automatic,” and all their kindred. The pistol—by which term I include all pistols, revolvers, automatics, and repeating or single-shot weapons meant for use in one hand—was essentially designed as a weapon for quick use at close quarters. It was a weapon of offence or defence with a limited range, particularly suitable for horsemen, and endowing their possessor with an advantage over enemies more skilled in the use of the arme blanche or physically superior to him.

In tracing the history and development of the pistol throughout the ages, we find that in the main it has always been the weapon of the mounted gentleman and companion to the sword. In the hey-day of the duelling period the disastrous cult of the hired bravo and bully imperilled the foundations of the code of honour, and as a revulsion towards a more equable method of settling differences, pistol duelling, with its infinitely greater equalization of risk, superseded the use of the small sword.

It is easy to infer that even then degrees of skill in the use of pistols were equally well marked as those of prowess in fencing; but as a matter of historical fact, while fencing was always the jealously guarded privilege of the gentry and military classes, the use of a pair of pistols was a necessary factor in the education of every householder, gentle or simple, during the period of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. It is safe to say that no household and few travelling carriages did not boast of the armament of a pair of pistols as a necessary defence against highwaymen, rogues, and masterless men.

During the early period of crude match-lock and arquebus, petronel and wheel-lock, body armour and plate of proof still survived, and it was only with the development of firearms and the consequent increased range of combat, together with the difficulty of constructing armour sufficiently strong to turn a ball and yet light enough to be worn without undue fatigue, that pistols began to come to their own.

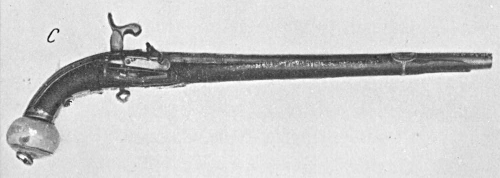

In the days when firearms were rare, and their use confined (owing to their costliness) to the nobles, we find that the early pistols and dags were modelled along the lines of weapons built to serve two purposes—those of a pistol, and a club or mace for use at close quarters—and they were usually, owing to their rarity, made the vehicles for some of the finest applied art of the period. During the Renaissance the craftsman was at the zenith of artistic achievement, and many an artist silversmith was also an armourer of no mean order.

Weapons were a necessity to every man, and upon them was lavished a wealth of loving skill and creative art that has lived to enrich the museums of our modern nations. In utility the firearms of the past were for the most part as accurate and efficient as could be achieved, considering the limitations of the tools at their disposal and the explosives with which they were acquainted. Love for their handicraft inspired the armourers; and many passages in the Memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini, a Florentine artist and silversmith of 1500-1571, proclaim how little has changed the amateur’s love for fine weapons.

With the invention of the percussion system an enormous impetus was given to the development of the pistol, and this invention was the point which made the revolver anything beyond a cumbrous and inefficient repeating weapon.

Revolving firearms of all kinds have been known since the dawn of the age of gunpowder, but the necessity for embodying cumbrous flash-pans, and the danger of other priming charges of loose powder lying in close proximity to the explosion and gas escape of the first discharge, had always made them ungraceful and dangerous weapons.

The percussion system changed that, and simultaneously in all countries the improved revolver made its appearance, but it remained for the citizens of the United States, then engaged upon the dangerous and arduous task of enlarging their territories and establishing their social code, to develop the Revolver.

To them and the French we owe the succeeding improvements and the applications of breech-loading which have since taken place, leading us step by step to that wonderful weapon, the modern revolver, and its ultimate successor, the automatic pistol.

Despite the claims of inventors of European origin, there is no doubt that the revolver in all its best applications is the outcome of American ingenuity and workmanship, and one may well term it their national weapon. To this day there lingers in the murderous Republic of Mexico the tradition of the terrible revolver-armed Texans of the early days of the Lone Star State, and even now, in out of the way parts, your skilled revolver shot earns the whispered sobriquet of “El Tejano” (“the Texan”) a man with whom quarrels are to be avoided!

As a factor in adventure and romance the pistol and revolver are all paramount, and to establish a library of books wherein all mention of these weapons was excluded would, I take it, exclude some two-thirds or more of our known standard works.

The love of weapons is deep-rooted in the hearts of manly men, and skill at arms throughout the ages has been extolled as becoming to the character and necessary to the development of all good citizens, so among the mass we always find a chosen few to whom the use and knowledge of weapons is an all-absorbing hobby, and whose ideal is the collection of representative, and even the rare and unusual, types of weapons in their historical development.

The average schoolboy has a wholesome interest in firearms, and at nearly every school occur a few rare youthful spirits who, in the pursuit of their hobby, defy the masters and the powers that be, revelling in the secret possession of firearms. This is a trait condemned by all who realize the danger of loosely handled firearms, but in extenuation one must plead that accidents with weapons in the hands of those who understand and love them are very, very few, whereas our journals constantly record deaths from the “did not know it was loaded” class—the bulk of fools who have not wit enough to master the first simple facts of use of arms.

Should parents be troubled by a son who loves pistols, I would advise them, first, to see that the weapons be of good quality, and not likely to burst, or go off accidentally, and secondly, to substitute, if possible, a gun or rifle for the pocket-arm, for it must be remembered that a pistol muzzle moves in a much smaller radius than the longer barrelled arms, and that with them accidents are more easily avoided and game far more easily killed. I do not believe in discouraging a lad in the practice of arms, although I would teach him care and economy by means of a Spartan severity in the matter of ammunition.

The reason for this is that when every cartridge is of value and supply exceedingly limited, your true boy learns perforce to perfect his shooting, does not indulge in risky shots likely to wound rather than kill game, and also learns a deal of woodcraft and the habits of his quarry.

I myself started a career of shooting with a flint-lock horse pistol “borrowed” from a trophy of arms. Powder was dreadfully scarce, and narrow-minded shopmen would not supply a boy of eight with it. Urged by these economic conditions my sole source of supply was rook-rifle cartridges, filched from a splendidly careless uncle; the powder from these blended with match-heads, and, later, a home-made meal powder of my own (God knows what risks I ran!) was all I had; newspaper wads, and, for shot, nicely graduated pebbles from the gravelled paths. With these difficulties to contend with I allowanced myself one shot a day, and, as a rule, devoted all the holiday morning to that shot. In the summer holidays, when young rabbits abounded, better game for a chi1d to stalk were never found. The old pistol would kill (perhaps!) at seven to ten yards, and to get within this range needed infinite patience, skill, and the development of a faculty for taking cover. I learnt more in that blissful summer than ever I could set out in cold print; learnt tricks of the wild, secrets of wind and track, that have stood me in good stead in pursuit of game in such divers places as Mexico or the North African Hinterland.

Of course it was all very wicked, but stolen pleasures are often sweetest, and it conveys the solemn moral—one shot, one kill.

To write a true book of all pistols requires a lifetime of study, travel, and research, and would fill many volumes, a delight only to the collector, and of little use to the ordinary man. My endeavour is to cover in this volume a brief summary of pistols in their wide variations, and to view them from the standpoint of the modern amateur of arms.

Exactitude in the matter of dates is often beyond one, but I have done the best to approximate as closely as possible.

I plead then in advance for my shortcomings, my disregard for all but the simplest tables, and my neglect of many quite charming firearms, whose individual peculiarities would interest us for more than a moment.

Criticism must find a place, for without it a book would be little more than a well-bound catalogue, and so I pray that those who disagree with me will remember that they also believe in their theories.