The following information on matchlock pistols comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

The origin of gunpowder is veiled in the mists of antiquity, and it is not known when it first came into use as a propelling agent. As a combustible and as a firework it is early mentioned, and its probable earliest use in war was as a rocket or bomb.

Gentoos’ code of laws, which was formed at about the same period as Moses, contains a reference. “The magistrate shall not make war with any deceitful machine, or with poisoned weapons, or with cannon and guns, or any kind of firearms,” but it is quite probable that “cannon” means “artillery,” which may be taken as meaning any kind of siege engine, and firearms might for the matter of that have been “fire arrows.”

In 1267 Roger Bacon alludes to gunpowder, and gives a recipe for its preparation, which he is assumed to have got from Marcus Graecus, who lived about the end of the eighth century, and describes a very sound method of making a large rocket.

Artillery were certainly in use at the Siege of Granada in 1325, and a year later the Gonfaloniere and Council of Twelve of Florence ordered brass cannon and iron shot for the defence of their city. Their use spread rapidly, and Edward III of England considerably astonished the Scotch by using “crakys of war,” in 1327.

The eastern origin of gunpowder is probably due to the fact that only in dry, hot countries is saltpetre found in its natural state, and it is certain that in 1626 the East India Company started to import saltpetre for the Government, though Continental Powers had to lay down special “farms” for its production.

The early powder was a simple mixture of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur, ground up together in the proportion of seventy-five of saltpetre, fifteen of charcoal, ten of sulphur. This was known as “meal powder,” and was used both as a charge and for priming.

During the reign of Elizabeth, the process of granulating or corning was discovered, by which the mixture is broken up into small grains. This process has been in use ever since, as it vastly improves the powder and gives it greater strength. The reason for this is that it allows the flame of ignition to penetrate more speedily between the grains than it could throughout a solid mass of meal powder.

Modern black powder has the grains glazed by the admixture of graphite in the corning mill, a process which partially waterproofs them. From time to time the nations varied the composition of their powder, and even powder for the private use of sportsmen was of very variable strength.

A century ago it was quite customary for sportsmen to test their powder in a little device known as an “eprouvette.” This was a little flint-lock pistol action machine, which, in place of blowing out a bullet, blew round a cover attached to a graduated disc that revolved against a spring. The position of the disc after discharge gave the reputed strength of the powder.

There is extant an account of a duel between Charles James Fox and Adams. They were at Brook’s, when Fox made some remark about bad Government powder. Adams, who was responsible, took the matter up and challenged Fox.

They met, and Adams fired, but Fox refused to, saying: “I’ll be damned if I do, for I have no quarrel.”

They shook hands after the encounter, and Fox, who was slightly wounded, said:

“Adams, you’d have killed me if it had not been Government powder.”

Nowadays, black powder has been superseded by smokeless compounds, but it is still on sale in country districts, and made on a commercial scale for blasting—anyway, it has made history for six hundred years; and whatever may be claimed for Berthold Schwartz, it is clear that gunpowder was not invented by a German.

The actual date of the invention of gunpowder is lost, and so also is the date of origin of the first pistol; but one can safely assume that certain specimens of Chinese matchlock pistols represent the first form of the pistol. These are for the most part small, immensely heavy castings, either round or octagon in section, and of exceptionally small bore in proportion to their thickness. The shape is usually that of a small trunnionless cannon, and they were unprovided either with stock or any system of attachment to a handle other than simple binding to a stick. No lock work or serpentin to hold the match is provided, and discharge was accomplished by merely pressing the lighted end of a length of match or rope upon the touch-hole. Some more modern ones are provided with a tang or extension, which folded back over the barrel and touch-hole, and was sufficiently springy to hold away the lighted match until the whole was grasped in the hand, when it was required to fire the piece. Later the usual lock and serpentin were adopted.

In Europe hand firearms were at first practically baby cannon, of which the human body formed the trail and a forked crutch stuck in the ground the support, and none of these can truly be regarded as pistols, as all needed two hands to manage—one to hold the weapon, and the other to apply the match. The next, and most important, development was the Matchlock, which was popular from its inception to the close of the last century, where a very perfect form of this weapon was used by the tribes of the Indian North-West Frontier.

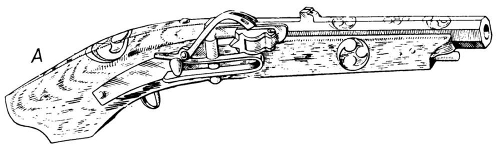

The matchlock in its simplest form consisted of a barrel fastened to a wooden stock by bands. In the rear of the barrel, and in a slot in the stock, was pivoted a curved lever or serpentin, the lower part of which—that is to say, the portion below the axis—was much heavier than the top. This weighted portion served to keep the jaws of the serpentin, which held a lighted match, away from the powder in the flash-pan. The match, a length of rope soaked in a saltpetre solution, was held so that when the lower end of the serpentin, which served also as trigger, was pulled up toward the stock, the glowing head descended into the loose powder of the pan, causing discharge. In later models the match was carried coiled upon the barrel, and the serpentin held but a small length of match, which one first lit from the main match, and then, by further pressure, plunged into the pan. The source of this invention of the serpentin, so called from its snake-like outline and fire-holding jaws, was probably due to the application of the releasing mechanism of the crossbow to the hand firearm. The flash-pan of matchlocks was always protected by a crudely fitted lid arranged to swing laterally, and designed to guard against accidental discharge and the effects of damp.

Although no European specimens survive, it hardly seems likely that short-barrelled matchlocks capable of use in one hand (pistols, in a word) were not in use, and there is no doubt that the knightly outcry against the use of firearms (and very loud it was) created a demand for a weapon easily usable by a mounted man, and it must always be realized that pistols are essentially a cavalryman’s weapons.

Hand guns were in use between 1375 and 1400, and the matchlock, usually known as arquebus, about 1476, being first established among the Swiss, but represented in 1518 before our King Henry VIII. at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. The Yeomen of the Guard, a corps established by Henry VII., were armed half with bows and half with arquebuses, and in Hans Burgman’s picture of the “Triumph of Maximilian” can be seen the complete equipment of the arquebusier of the sixteenth century.

The pistol, so called either from the fact that its calibre corresponded with the “pistole,” the coin, or from its reputed invention at Pistoia, in Italy, was common in Germany in 1512, and was adopted by the French cavalry in 1550. One Caminelleo Vitelli, of Pistoia, is reputed to have invented it about 1540, but its undoubted previous popularity disposes of his claim.

About the period of 1510-1520 there seems to have been an outbreak of enthusiasm among inventors, due possibly to the stimulus of the wars between France and the States of Italy, and about this time occurred the invention of a new system of ignition which was about to reverse all previous conceptions of the limited utility of firearms.

The European matchlock differs from the ordinary Oriental model in that the serpentin points toward the stock, as does the cock of a wheel-lock. In all Oriental arms the serpentin is reversed and occupies a position similar to the usual hammer of a firearm, pointing from the stock toward the barrel.