The following information on modern military arms and the Webley revolver comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

Since the invention of the revolver it has invariably been regarded as a high-class military weapon, and the legitimate successor to the pair of pistols which formed part of an officer’s equipment ever since the sixteenth century. Nowadays the military weapon is the standard type from which all other variations of size, design, or calibre are taken. All officers of modern armies are equipped with one or other of the standard makes of military revolver or automatic pistol, and in some branches of the Services these weapons are issued to the rank and file as well as non-commissioned ranks in addition. The U.S.A. cavalry carry the pistol as a side-arm, and British artillery drivers, Army Service Corps, and non-commissioned officers of many branches, are also equipped with them, as are now the Motor Cyclist despatch riders of the R.E. Special Reserve and Cyclist Battalions, and certain machine-gun crews. The U.S.A. Army and Navy were equipped with .38 “Special” calibre Colt’s or Smith and Wesson’s revolvers, and the .45 U.S. Service automatic Colt is now being issued. The British Army uses the Webley Mark IV. or Service Model .455 calibre revolver, while the Navy is now equipped with the .455 calibre Webley-Scott automatic pistol.

The French Army uses a special revolver, with solid frame and extraction similar to the Colt and Smith and Wesson systems; but the cylinder swings out to the left instead of to the right, and is chambered for a special copper-coated bullet, high velocity smokeless cartridge of 9 mm.

The German Army uses the Luger or Parabellum automatic, and the Russians employ the Nagant—a revolver patented in 1895, and fitted with a wedge action, holding the cylinder close up against the rear of the barrel to avoid gas escape. Various other countries use the 9 mm. Browning military model, the Mannlicher, and the Bayard automatics as standard arms.

The military revolver is always the model to set the standard, and the little pocket revolvers, or special target models, are merely reductions of variations from standard types.

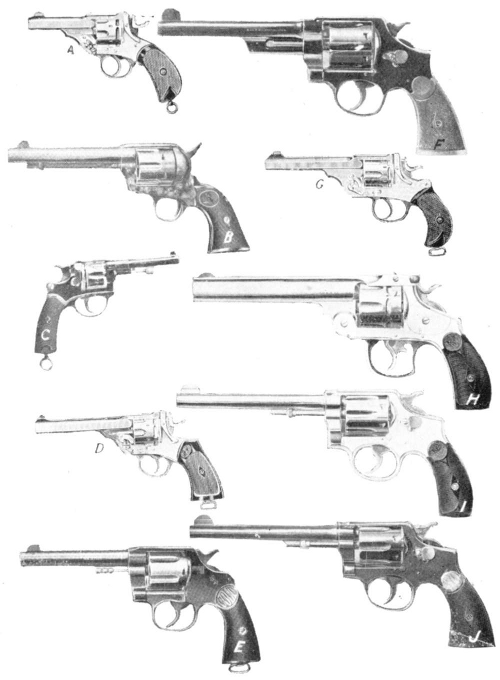

After the 1890 period of development had passed, Colt’s set to work to perfect a self-ejecting model to compete against the Webley and Smith and Wesson types. They selected the solid frame swing-out cylinder model, with hand-operated simultaneous ejector; this type of arm has the benefit of greater rigidity of frame than any of the “breakdown” or “tip-up” action weapons, and further maintains the cylinder in better alignment with the barrel. This standard model of Colt revolver is now made in a complete range of barrel lengths, calibres and sizes ranging from the .45 New Service Army model through the .38 special military and police calibres into pocket weapons and even the .22 target revolvers. There are three distinctive frame sizes—the New Service, or largest, bored for the .45 Colt; the .44-40, .44 Russian; .38-40 and .450-455 British cartridges. The “Army Special” or “Officer’s Model” of medium size and weight, made for the .41 long Colt, .38 S.W. Special (the U.S.A. Army cartridge) the .38 long Colt and the .32-20 follows. Next comes the “Police Positive” frame, with a variation of calibres from .38 Special, .380 Colt, .32-20, .32 S.W., and .32 long Colt. The .22 Police Positive Target revolver is the only rim-fire weapon, with the exception of the Colt Derringer pistol, that is made, and with the exception of this last all the above weapons are double action.

In 1902 the Smith and Wesson firm issued their first solid-frame military arm, in which the familiar breakdown action was abandoned. All the previous models, with the exception of the S.W. Hammerless New Departure Pocket Revolver, were thereby rendered obsolete—a class which includes the .44 S.W. Russian model single-action target revolver, the double-action .44-40 and .44 Russian, and all large size breakdown action Smith and Wesson revolvers.

In 1905 the shape of the stock was changed to a square-shouldered pattern, and in 1908 the big .44 solid-frame S.W. target model revolver was issued.

The Smith and Wesson solid-frame revolver is similar in design to the Colt, the same principle of double action and simultaneous ejection by means of the swing-out cylinder being employed. The lock work of these revolvers is noteworthy, mostly spiral springs being employed, and the exquisite internal finish and smoothness of action being a triumph of mechanical perfection. The cylinder of these models revolves from right to left in place of the usual reverse motion, and in the large calibre model a special front locking device is incorporated in front of the cylinder, with a view to increasing the rigidity of the cylinder bearing. A range of frame sizes and calibres to take the .44-40, .455 British, .38 Special, .38 Colt, .32-20 W.C.F., and .32 S.W. long cartridges are made, the .455, .44, and .38 Special being standard military sizes and obtainable in the target model.

The Webley design of frame, with the safety stirrup locking bolt for the top strap, has always been so strong and well made that no need for a solid-frame action was ever manifested, even when the heaviest charge of smokeless were used in the weapon. The series of Webleys ran up to the Service model .455 Mark IV., with 4 or 6 inch barrel; the 6-inch Army model, with curved “parrot beak” handle, still the favourite Army officer’s weapon; the exquisite 1892 W.G. target model, with special grip, 7 1/2-inch barrel, and target sights; and the later improved model .455 6-inch barrelled Webley-Scott, in which a shorter hammer travel and different shaped grip more useful for cavalry use were adopted. All these weapons were .455 calibre for the Service cartridge, but the firm also issue a range of miniature models for pocket and police use in the .38, .380, and .320 calibres, the latter weapon being made hammerless, or with a special flush-hammer and small holding-down barrel catch for pocket use.

This summarizes the list of the modern revolvers made by the three great arms firms, and in later chapters the special weapons suitable for special purposes will be indicated. As to the differences between them as shooting weapons it is impossible to judge. They are all of excellent design and manufacture, and it is purely a question of personal predilection, one man choosing one make, one another; though for quick double-action work there is no doubt that the Webley is superior to the other two, while their target efficiency for single-action work is about even.

The chief requisites of a military pistol or revolver are a capacity for hard wear under adverse conditions (for upon Service they may have to go for long periods without cleaning or attention), sufficient strength to resist without damage such accidents as being dropped, and a complete interchangeability of parts to facilitate repairs.

The stopping power of the weapon is the point of most importance, and it is universally admitted that calibres smaller than .45, whatever the velocity of the bullet, do not act satisfactorily as “man stoppers.” Most modern Continental automatic pistols err in this respect, and it must be remembered that a man in action, unless hit in a vital spot, such as the brain or heart, when the effect is instantaneous, has still sufficient energy left to be able to close with and kill his opponent with a bayonet, despite many small-bore rifle and revolver wounds upon him. The effect of a revolver bullet should be to develop as much shock as possible when it hits its target. The tendency of the nickel-covered small calibre high velocity projectile is to go clean through a man and travel for a long distance the other side; while the soft lead bullet of the big bore .45 revolver develops and utilizes most of its energy inside the body of the man hit.

A good instance of the value of large-bore lead bullets as against high velocity automatics occurred a few years ago in Mexico when some peons attacked two white engineers. One—a German—was armed with a Parabellum; he shot his adversary four times, each shot being in a vital spot, but the peon closed with him and ripped him up with a machete. The other man was armed with a .44-40 Colt Frontier; his first shot hit his adversary in the shoulder, and the shock was sufficient to knock the man down, allowing him his reserve five chambers to devote to the rest of the gang.

A reasonable objection to automatics as military weapons is their tendency to jam when dirty, an objection from which the revolver is reasonably free. Another most important point is that of mis-fires. In a revolver a mis-fire is of slight effect, as the next chamber can be fired within half a second; but in the automatic several seconds must elapse, and both hands be employed to “break” the action and eject the faulty shell.

The first official military revolver used in England was the Enfield of .442 calibre, later made in .450. This pistol was of the breakdown type, and automatically ejected the cartridges as the cylinder slid forward along its rigid axis. This weapon gave place to the Webley self-ejector Mark I. of .476-455 calibre, the long .476 cartridge having a bullet with a deep recess at the base, in which fitted a hard clay plug, which expanded the base of the bullet to take the rifling. Officers have to supply their own revolvers, and any weapon of approved pattern and .455 calibres, to take the Service cartridge, is accepted.

Solid frame pistols of the long-barrelled R.I.C. model, Tranter’s or Adam’s, were popular about the 1885 period, but the short .450 cartridge proved insufficient to stop the Soudanese “Fuzzy Wuzzy,” and among many officers double-barrel .20 bore pistols, firing either a charge of slugs or the short .577 Snider size cartridge, were popular.

Later the .455-476 cartridge was developed and adopted as standard, and Colt D.A. Frontier models were as popular as Webley’s. About this time Edwinson Green, of Cheltenham, developed a revolver of graceful lines, embodying the advantages of the Webley stirrup fastening and the grace of the Smith and Wesson, but, unfortunately, the manufacture of these arms was not proceeded with.

Occasional specimen weapons by Kynoch, Silver, and numerous makers are found, but from this time onward the three great firms of Colt, Smith and Wesson, and Webley are the only ones of any consequence.

The weapons now permissible in the Army are any of these makes that are double-action, of not more than six inches in barrel length and chambered for the .455 cartridge with 6 1/4 grains of cordite. The first automatic pistol built for the British .455 cartridge was the now obsolete Webley-Fosberry, a six-shot weapon of the ordinary revolver type, but in which the barrel and cylinder recoiled along guides, cocking the arm and rotating the cylinder to the next chamber. This weapon possessed the drawbacks of a revolver, and only operated as an automatic when held rigidly, for if fired with a slack arm, or, as is the case with many expert quick shots, the shooter was accustomed to allow the muscles of his arm to absorb part of the recoil instinctively, the arm refused to function. It was also higher in the hand than most revolvers, and consequently jumped unpleasantly.

The W.G. and Webley-Scott patterns of revolver differ but slightly—differently-shaped handles, cylinder release gear, and breech-block plate being fitted to the latter model, which has also a shorter trigger pull.

The Webley-Scott .455 automatic issued to the Navy is chambered for a special rimless cartridge of 220 grains bullet, and is readily dismountable by hand. It holds eight cartridges in a magazine in the handle, and is equipped with a large safety-grip on the butt, rendering the weapon innocuous unless gripped in the hand. At the moment of firing barrel and breech-bolt are locked together. When the two have travelled in this position a short distance to the rear, the barrel rises upon its diagonally situated guides, and the breech-block alone travels back, ejecting the empty case, cocking the hammer, and reloading the chamber. When empty the mechanism remains open till a new magazine is inserted, when pressure upon a button releases the breech-bolt which loads the chamber, leaving the weapon ready for immediate use.

The design of the Webley is serviceable but ugly, and the shape of the handle set as it is—almost at right angles to the barrel—is such as to render instinctive shooting with this weapon less easy than with the curved handle pistol or revolver, or the automatic with shaped or slanting handle of efficient modern design. It is, however, a powerful and exceedingly accurate shooting weapon.

The Colt .45 military model is now also made to take the British Naval Service .455 automatic cartridge, but as a military automatic has much more to recommend it than the Webley, the slanting grip and easy natural alignment of the weapon rendering it a splendidly efficient weapon for service use.

The safety devices are worthy of note, and the whole design is one that combines the improved mechanical efficiency of an automatic pistol, with an attempt to secure the natural shape of a pistol adapted to the needs of the anatomy of the human hand, a point of design that less progressive makers see fit to ignore.

The accuracy of automatics surpasses that of the best military revolvers, and the speed of firing (normally three to four shots per second) is three times that of a double-action revolver in the hands of an ordinary shot. The objection to the use of automatics for target work is that they have mostly fixed military sights fitted, and that the ammunition is much more expensive than that used in revolvers of equal calibre. The balance is usually poor, and the trigger-pull of a dragging, unpleasant quality, incapable of delicate adjustment. The worse makes have the line of sight too far above the hand, and the racket of mechanism and the loud report all conspire to breed a tendency to flinching. The novice should avoid automatics, as they are far harder to shoot with than revolvers, and it is far better to learn the elements of pistol shooting on a safe and simple weapon rather than the complicated and cumbrous “latest little thing in automatics” advanced by the astute gunshop salesman.

For use as an English Army pistol the “W.G.” Officers’ model, or the Webley-Scott Army revolver, according to which grip you prefer, can be cordially recommended. The New Army Colt is also an excellent weapon, as is the “Webley-Wilkinson,” but as different makes suit different types of hand, it is always best to choose your pistol personally, rather than leaving it to a friend to select.