The following information on pocket pistols and revolver comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

The bulk of revolvers and automatic pistols are made in sizes small enough to be carried in the pocket—powerful weapons, but easily concealed and portable.

The average Englishman has little idea how widespread is the habit of carrying a pocket pistol; it is certainly unusual in England, but almost customary in the U.S.A. and Continental countries. A brief inquiry into the sales by English gunsmiths of pocket pistols to English folk not travelling abroad would probably astonish the casual inquirer. After all, it is better to be efficiently armed than not; and ever since the first prehistoric man invented the sling or the bow, weapons that kept the enemy at a distance and disqualified mere personal strength have been popular.

For the ordinary man a pocket pistol is not an essential; but for anyone whose work or inclinations leads him to strange places in our own cities, or even as far afield as Paris, a pistol is a wise precaution, as it insures that, if you are molested, you hold equal or superior cards to your adversaries. Strangely enough, the English “rough” is not sufficiently familiar with firearms to be afraid of them, and is more or less certain that you will not dare to use them. A display of cold steel, or, for choice, a sword-stick, on the other hand, scares him off at once.

In Paris the indiscriminate apache uses firearms with absolute nonchalance, and street battles between rival bands are as casual as were similar affairs between Bowery or Chicago “toughs” or “gunmen”; as a result, wherever the criminal classes use weapons, the respectable classes also adopt them for private self-defence. The police all the world over share the trait of never being on the scene when wanted.

One cannot deal with the moral question of whether shooting, or even killing, in self-defence is allowable; but in defence of the matter of killing, it must be remembered that, when one is in personal danger and the victim of sudden attack, shooting is probably instinctive, without the least fraction of time wasted in sighting. The pistol is drawn and fired at a speed and during a period of nervous tension that probably entirely inhibits all but a purely instinctive mental process, and one shoots as one points or throws a ball—instinctively. There is only one rule to be remembered, and that is—shoot first.

The “shooting through the pocket” myth is dangerous, for even the expert shot cannot depend on getting his man in this way unless he is within three or four yards; and the author discovered by personal experience that an automatic discharged through the pocket is capable of one shot only. Having occasion to scare a rather ugly customer, I fired a .32 automatic of first-class American manufacture straight through my coat-pocket into the earth. The empty case was prevented by the enclosing pocket from ejecting clear of the action and jammed the weapon, putting me out of action. Luckily, no second shot was needed.

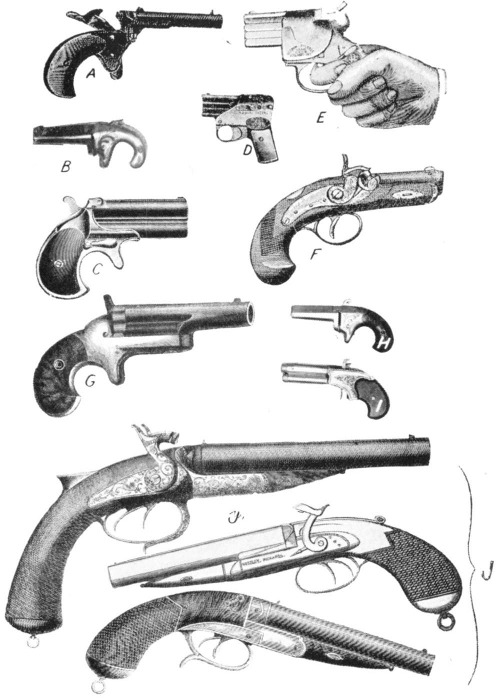

The shooting through the pocket idea was certainly useful in the days of short Derringers and quarrels with gamblers across a table; also in the days of the “southern gentleman,” who wore a long black tail-coat, with a pistol in each tail-pocket, as the sweep up of the tails and pistol allowed him to fire from the hip with comparative freedom of action. The modern lounge suit is practically impossible for the purpose, except in the case of a corps-à-corps struggle. If you have time to draw a pistol, and your enemy has not “got the drop” on you, draw and shoot. You will have a six-to-one better chance than shooting at random through your suit.

In the old days “out West” the double-action, or self-cocker, revolver was condemned by experts, “bad-men,” and sheriffs alike. They claimed that with it the average man, drawing hastily in a quarrel, sent the first bullet into the floor by drawing the trigger out of sheer flurry and nervousness. The action of cocking a single-action pistol took just long enough to steady one’s nerve for the shot.

There is a good deal of wisdom in their summing-up, and it is a point that is accentuated by the bad design of most modern automatics. Pick up the average revolver or target-pistol and snap without sighting at a target, and you will probably find when you glance along the sights that you had instinctively pointed more or less true with it. Try this with any square-handled automatic, and you find that your bullet would hit the ground about ten yards in front of you. This is because the revolver handle is curved to suit the natural grip of the hand, whereas the square shape of the automatic necessitates a strained unnatural position of the hand, the wrist having to be much more “bent upward” to bring the barrel into true alignment with extended arm and eye. Practice will cure this; but the unpractised shot, shooting instinctively with an automatic, is much less dangerous than the same man with a revolver or curve-handled pistol.

The advantages of the automatic pocket pistol are rapidity of fire, and flatness and compactness in the pocket; the disadvantages—unnatural alignment, tendency to jam, and the danger common to all magazine pistols of taking out the charged magazine and forgetting the live cartridge in the chamber.

The pocket revolver is heavier, clumsier, and holds fewer cartridges than the automatic, but it is, owing to the projecting handle, easier to draw and easier to shoot with.

In making up one’s mind over the choice of a pocket pistol or revolver, it is well to remember that if the arm is merely to be carried with only remote chances of needing it, an automatic is excellent; but if it is for probable use, and as a permanent article of wear, regarded as more important than a collar or tie in the country or circles in which you propose to travel, the revolver is much better for your purpose.

The Colt hammerless .25, .32, and .380 automatic pocket pistols are good, and are equipped with a safety-grip in the handle, which prevents the weapon being discharged unless safely held in the hand. Falls or accidental knocks cannot discharge the weapon. The same applies to the Browning’s or F.N. pistols of latest design and similar calibres.

The Webley .25, .32, and .380 automatics are also sound pocket weapons, but all except the new .25 have the disadvantage of an outside hammer, and are slightly less convenient in the pocket. The .32 M.P. Webley has been adopted by the London Metropolitan Police as their official weapon.

The Savage .32 and .380 ten-shot automatic has many better points than most pocket pistols, including a very good grip, greater magazine capacity, and light weight; its shooting is also good.

The pocket Mauser of .25 calibre is, like all the weapons of this firm, well-made and reliable, but for its small calibre is unduly large for the pocket. The Bayard, on the other hand, is little larger than the average .25 pistol, and is made in .32 and .380 calibres, and is the smallest large-bore automatic on the market.

The Smith and Wesson .35 automatic is rather similar in external appearance to the Webley, but the special cartridge necessary renders it less useful than other makes for standard ammunition that can be got all over the world.

The .25 Victoria is an inexpensive Continental weapon, and is the smallest .25 made; its mechanism is not well finished, but exceedingly simple, and one of this make in the author’s possession has proved an exceedingly reliable little weapon.

On the whole, avoid cheap European automatics, and only buy first-class productions. The cheap stuff is unreliable, inaccurate, and even dangerous, while the saving of a few shillings does not warrant the possible accident that may result from their use.

In automatics, as with revolvers, the larger the calibre the more effective the arm, and though a .22 or .25 may be very pretty and portable, nothing under the .32 automatic or the .32-20 W.R. revolver cartridge is useful as a stopping weapon, and of all sizes the .380 or .38 S. and W. is the best.

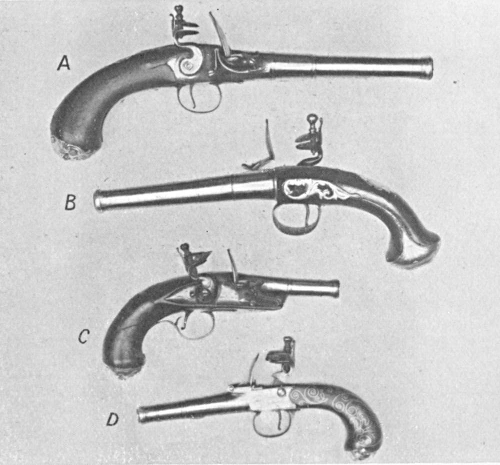

The reader may object that a pocket pistol that will wound is amply sufficient for self-defence, but it must also be remembered that unless the wound is enough to disable the adversary it is of no use. The smaller calibres may wound a man, but not enough to embarrass him and prevent his killing you with a knife or “life preserver,” while the big smashing effect of a large calibre bullet will immediately put him hors de combat without of necessity proving fatal. For a self-defence pocket pistol, neither heavy powder charge nor great velocity of the projectile have much value; it is preferable to use a heavy bullet and a small charge—a principle employed in the old-fashioned Derringer pistols, and proved by years of experience to be sound.

The pocket revolver should either be hammerless or devoid of projections to catch in the pocket or clothes when drawing the arm. The hammerless pistol has the additional advantage of being safe against accidental discharge, as it cannot fall upon its hammer and so fire the cartridge.

The best modern hammer revolvers are also fitted with an intercepting device between hammer and firing-pin or hammer-nose and cartridge; the Colt Positive Lock is a typical example.

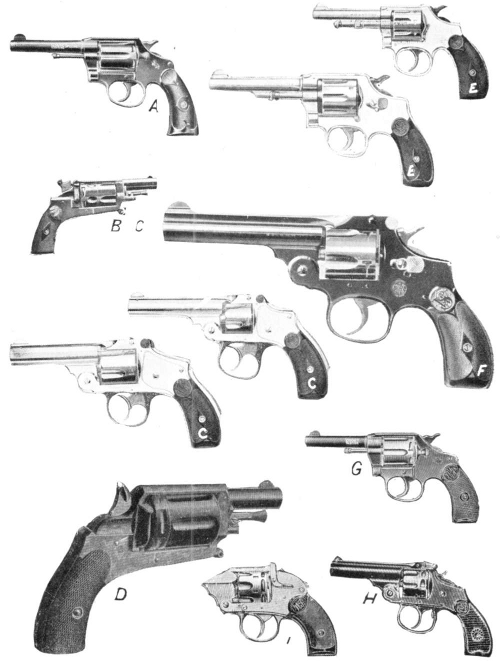

The .38 and .32 Smith and Wesson hammerless safety revolver is one of the best pocket pistols of its type, as it embodies the grip safety with its hammerless feature. The .32 Webley hammerless has also merits, but the safety device fitted does not act automatically—a point that may be overlooked, and leave the owner with a locked weapon in his hand, if he forgets to operate it when drawing the weapon.

Hammerless revolvers are essentially the safest of all firearms, as they are of necessity double-action. This involves a considerable exertion of pressure on the trigger to operate the mechanism, and renders the weapon fairly safe in the hands of children or people unused to firearms. Their disadvantage is, of course, that they cannot be used for single-action target practice, or anything but double-action shooting.

Hammer revolvers can be used either single or double action, but unless fitted with some intercepting device between firing-pin and cartridge are dangerous if dropped hammer downwards. Weapons not fitted with any safety-lock should always be carried with the hammer down upon an unloaded chamber, and never by any chance left at full cock.

The Webley Mark IV. .38 is a compact and serviceable six-shot weapon—a miniature of the Service arm of .455 calibre.

The Smith and Wesson .38 Perfected is intermediate between their tip-up and solid-frame models, and though retaining the tip-up action and automatic ejection, has the handle and locking device of their solid-frame models. These are similar to their military models, and are made in various calibres and barrel lengths—.22, .32 S. and W., .32-20 W.C.F., .38 S. and W., and .38 S. and W. Special. The 1902 model has a rounded stock, the 1905 a square. Numerous Spanish imitation Smith and Wessons are made, and though externally replicas of the genuine pistols, are distinctly to be avoided.

The Colt Pocket and Police Positive models vary only in the shape of grip and length of barrel, and the action is identical, the solid frame, swing-out cylinder, ejection and positive lock features being exactly similar. They can be got for the following cartridges: .32 Colt, .32 S. and W., .32 Colt New Police, .32-20 W.C.F., .38 Colt, and .38 S. and W. Special. Several models take several different .32 or .38 cartridges of varying charge.

Among other pocket revolvers, the Continental “Velo-Dog” patterns are deserving of mention. These pistols are made in all concealable patterns of hammer, hammerless, self-ejecting, and plain models, to take a long centre-fire, high-velocity cartridge of 6 mm. calibre, known as the Velo-Dog. The bullet is of lead, copper coated, and the velocity and penetration exceptionally high. The same type of cartridge is used in the 9 mm. (.380) French Service arm, and pocket revolvers for this cartridge are also common.

Many Continental pistols and revolvers are now made for the .25 and .32 rimless automatic cartridges; but these weapons, though outwardly well finished, are seldom well made inside, and almost invariably made of indifferent metal, badly, fitted, and with terrific “pull-offs.” Except for their small size, coupled with the powerful charge, they have little to recommend them.

The cheaper kinds of American revolver are, as a rule, efficient as pocket pistols, but will not stand up to much continuous use without wearing out speedily. They lack the smoothness of action and accuracy of the first-class makers, but are better than most Continental weapons, and are efficient and safe for house or self-defence arms.

The single-shot Colt .410 rim-fire Derringer, and the double-barrel under-and-over Remington Derringer, are still made, and as large-bore, self-defence pistols for close work are preferable to many small-calibre repeating weapons. Although single action, and almost, if not quite, obsolete, they still have a steady market, and are now, as ever, the best weapons of their class. Many people prefer a single heavy-shot pistol to a small-bore repeater or revolver, and there is much to commend their choice; they are also the cheapest model of first-class pistol marketed.

In self-defence work, it is well to remember that an unloaded revolver is of less use as a weapon than half a brick in the end of a stocking, and that you should never draw a pistol unless prepared, if necessary, to shoot. Looking for a burglar with a lighted candle is as stupid as hunting for an escape of gas with the same illumination. It makes you into a target—not the burglar.

The law on the subject of shooting burglars is rather vague—technically he should put you in peril of your life (i.e., have first shot); but, actually, a burglar is presumably an armed and dangerous criminal. Such a man, having been called on to surrender, presenting a harmless spanner, or, say, a pipe stem, or attempting to draw a concealed something from his pocket, could hardly expect one to wait to see if his implement was a real pistol and really loaded. On the other hand, a burglar shot in the back might lead to a lot of judicial unpleasantness.

It is wise to take advantage of all possible cover, and, except in countries like certain Latin-American Republics, where a wounded man means more legal trouble than a dead one, avoid killing if possible, but don’t run risks yourself.