The following information on revolver and pistol equipment, accessories, cleaning, etc. comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

The first secret of good shooting is the possession of a first-class weapon, and unless great care and attention is paid to the cleaning of firearms they rapidly degenerate in efficiency.

Revolvers and pistols must be kept entirely free from rust and leading, and to insure this it is essential that the weapon should be cleaned as soon as you have finished shooting.

In the old black powder days the amount of fouling produced by each discharge was enormous, and left a black residue of unburnt carbon and potassium sulphides in the barrel.

Each succeeding shot increased the thickness of the deposit of fouling, till after twelve shots the accuracy of the weapon was perceptibly affected and the recoil considerably increased.

Black-powder fouling was hard to remove, except by the use of boiling water. In the days of muzzle-loading single-shot pistols it was easy to detach the barrel and breech-block from the stock and plunge the whole in boiling water, which speedily scoured out the soluble deposit. The barrel was then withdrawn by means of a wooden stick pushed into the bore and set on end to drain and dry. The hot metal speedily evaporated the remaining water, and left the barrel clean and dry. It was then oiled over inside and out and remounted on the stock.

With the increasedly complicated mechanism of revolvers, the danger of getting water into the lock or ejecting mechanism, where it would be overlooked and likely to rust the delicate parts, led to its disuse, and black-powder revolvers were cleaned with tow and oil or bristle brushes in the ordinary dry way. This meant a good deal of messiness, and was a tiresome job.

Nowadays, the fouling left by smokeless powder is so little that round after round can be fired without its affecting the accuracy of the weapon; but the fouling of all smokeless powders has particular vices of its own.

The black-powder fouling was not instantly injurious to the barrel metal, as it consisted for the most part of neutral or alkaline salts. The residue of smokeless is, on the other hand, acid, and immediately attacks the metal of the barrel and chambers.

Smokeless powder is composed of varying proportions of nitro-cellulose and nitro-glycerin, dissolved together with acetone, and pressed into various forms, such as grains, sticks, discs, etc. These, on explosion, liberate a quantity of nitric acid gases, which permeate the residue or fouling, and are exceptionally corrosive.

To get rid of these it is necessary to clean one’s weapons with “nitro-solvent” or “cordite cleanser,” which are merely blends of mineral oil, some alkali, such as caustic potash and phenol or carbolic compounds. These alkalis render the acid salts of the residue inert and easily removable.

All .22 rim-fire cartridges exercise great corrosive effects, as the heavy charge of fulminate of mercury liberates a variety of acid gases, and cordite cleansers should always be used to clean weapons used with this cartridge.

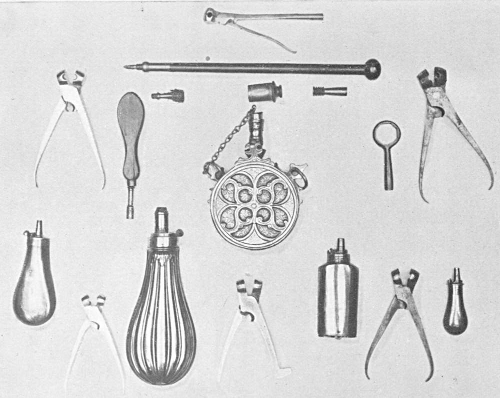

A cleaning kit for each calibre of weapon that you use is the best equipment, but on occasion a single cleaning rod to fit them all, and special bristle-brushes for each, will serve.

The requisites are a twisted wire bristle-brush fitting the bore fairly tightly, a cleaning rod of brass or soft metal, or sometimes wood for large bores, to which screws a jag for patches and a loop for holding a special oil patch, a bottle of special gun oil, and one of cordite cleanser.

The great point is to avoid all chance of damage to the edges of the rifling, and it is always best to clean weapons with break actions from the breech end, as the slightest damage to the rifling, near the muzzle, may affect the shooting badly.

After shooting, clean out the barrel and chambers with a bristle-brush dipped in cordite cleanser. Then clean with flannel patches wrapped round the jag of the cleaning rod, until they come through the barrel clean, showing no signs of fouling or dirt of any kind. It should be possible to draw a white silk handkerchief through the chambers and barrel of a properly cleaned revolver, without it showing the slightest speck of dirt. When it is clean, and before putting it away, oil it thoroughly inside and out.

Pistols, even if unused, should be examined and cleaned once again about three days after putting them away, in case a little fouling has been overlooked, and even if kept in air-tight cases an examination every month is a good rule to go by.

Apart from fouling, there is a disagreeable feature known as “leading,” which is particularly noticeable in small-bore high-velocity arms, such as automatic pistols that fire a nickel patched bullet, and to a greater or lesser degree in all revolvers and pistols.

This leading consists of the surface of the rifling becoming covered with a thin plating of lead or nickel, which is hard to see when you are cleaning, as it takes the same metallic polish as the barrel itself. Underneath this plating there is always a certain amount of acid fouling which eats away the barrel, causing slight “pitting” or corrosion marks, which will soon ruin the barrel for good shooting.

To avoid this, careful cleaning is usually enough, but should it occur the only thing to do is to clean the barrel with any of the special leading or “cupro-nickel solvents” sold for the purpose. In .22 weapons, where the leading occurs frequently, cleaning occasionally with a mercury paste, or simply filling the barrel up over-night with mercury, will easily remove it, as the quicksilver combines to form an amalgam with the metallic lead, and does not affect the steel barrel.

When cleaning a weapon do not forget to clean the breech of the barrel and the mouths of the chambers, as well as the inside of barrel and chambers. At these points wear occurs quickly, due to the escape of gas between barrel and cylinder, and neglect increases the size of the gap and decreases the shooting capacities of the weapon.

Pistols should always be kept in wood or leather cases, not left loose in their holsters. These cases should be as nearly air-tight as possible, and fitted with a good lock and key to prevent the weapons being meddled with.

A complete case should be equipped with cleaning gear, oil bottles, screw-driver, etc., and should have a partitioned section large enough to take a box of cartridges suitable to the weapon. The cleaning rod should be in a different compartment to the barrel, so as not to knock against it in transit.

Excellent leather pistol-cases fitted with a carrying handle and straps are now the usual equipment of a target shot, but some people prefer the French system of enclosing the polished oak or mahogany pistol-case in a separate leather cover.

Holsters are made in several patterns: the usual Army model, with a buttoned flap covering the whole of the weapon, the American “cowboy” holster, and the shoulder holster. Of all patterns of holsters the only one that is any use for wearing on service is the “Olive” or cowboy type. This is open at the top, has the side cut away to admit the finger direct to the trigger, and has a hole bored in the bottom to let out rain or dust. With this type of pistol holster, which is worn on a cartridge belt that hangs from left hip to right thigh, the hand falls perfectly naturally on the butt of the weapon—ready for instant drawing.

A revolver worn in this way is the best equipment for the mounted man, but it should be noted that if the barrel is over six inches long, it is uncomfortable and likely to bump on the saddle cantle when the holster is shifted to the riding position on the right buttock.

The shoulder holster is an excellent device for carrying a concealed weapon, and consists of a leather holster of the Olive type, suspended from a loop of leather, which fits over the left shoulder, and is further secured by a light strap passing round the back and over the breast under the waistcoat. In this manner a large revolver can be carried inconspicuously, but readily accessible. A certain amount of practice is needed before the art of drawing the weapon swiftly can be mastered.

Weapons not in use should always be kept in cases, not holsters.

A queer device of combining an electric torch and a revolver has been recently marketed; it is quite impracticable, but deserving of mention. A tube carrying a battery, a mercury switch, and a series of lenses, on one of which is marked a black spot, is mounted upon the barrel and parallel to its axis. At 12 yards: a circle of light about 2 feet in diameter, with a black spot about 4 inches wide in its centre, is thrown upon the target. This light only comes on when the pistol is held level and horizontally, and the tube is adjusted so that the bullet hits the centre of the black spot. The idea is excellent, but in practice it is found that the black spot wobbles all over the place, and at the moment of trigger pressure the circle of light leaps to one side in the most disconcerting manner. As a weapon for house defence it might prove useful at close range, but as an effective combination of an electric spot light aiming device it is of no real value.

So much time has been wasted by inventors on similar devices that it is worth mentioning, if only to save further expenditure of time and money on an unsatisfactory principle.

The Maxim silencer as used on rifles has been applied to pistols with varying degrees of success. The application of the device to pistols or revolvers is illegal in some countries, and very rarely applied in others. I have never seen weapons so fitted exposed for public sale, but have seen one or two privately adapted. In practice they are not very efficiently silent, and tend to render the weapon unwieldy and inaccurate.

The system of fitting special “target grips” or handles to pocket or police revolvers with small butts is an excellent method of improving the efficiency of the weapons as target arms, the larger grip giving a steadier and more effective purchase for the hand.

If it is desired to form a cheap but permanent target handle for a revolver, a good plan is to bind the whole butt, metal butt strap, wooden stocks, and all with ordinary electrician’s insulating tape, till the whole is covered with three or four loosely applied layers. The weapon should now be thoroughly warmed in a tin box in front of a fire in order to soften the tape and render it properly pliant and adhesive. It should then be tightly gripped in the firing position, and held so until cooled down and “set.” It is as well to cover the hand with loose talcum powder before gripping the hot weapon, as the rubber compound in the tape oozes out and adheres to the skin. Petrol or benzine will remove it.

This principle gives you a good non-slipping grip perfectly adapted to your own hand, as the tape moulds itself exactly to your grip. A handle so treated and afterwards varnished will stand years of wear. Weapons for use in the Arctic, where it is impossible to touch bare metal, should also be so treated.

Holster stocks or attachment stocks of any kind are not of much use as fitted to pistols and revolvers. They only turn a good pistol into a bad carbine. For some kinds of work a wire stock may be of use as fitted to a long-barrelled target pistol for hunting work, but on the whole it is better to carry a folding .22 rifle than a hybrid weapon. The revolver is not meant for long-range work, and though good shooting may be done with the Service weapon up to 100 yards, and fatal effects obtained at 400 yards, its limit of efficient accuracy is about 75 yards, and its probably extreme range well under a mile. Some weapons, like the Mauser, are sighted for extreme ranges, but even used as carbines their accuracy at anything over 400 yards is exceedingly variable. It should never be forgotten that though a weapon may only be efficient up to 100 yards, it may kill at 400, and extreme care should be used that bullets never overshoot a butt or are fired “up into the air,” regardless of where they may fall. Shooting at a moored barrel 250 yards out at sea, the firing-point being up on a cliff about 100 feet above sea-level, I found that bullets from an ordinary .38 pocket hammerless Smith and Wesson went through both sides of the target—an efficient instance of the power of a small weapon a long range.