The following information on wheel lock pistols comes from The Book of the Pistol and Revolver by Hugh B. C. Pollard. The Book of the Pistol and Revolver is also available to purchase in print.

Up till 1515 all firearms had been handicapped by the necessity of having a burning match attached. This was undesirable and dangerous for many reasons, notably that the flame and smoke of the match betrayed the position of the gunner, a point that rendered the match-lock unsuitable as a sporting weapon or upon such military enterprises as night attacks. After all, the process had been cumbrous, for the musketeer had first to load with coarse powder, a tow wad, a bullet, and another wad, and then to “prime his piece”—that is to say, to fill the flash-pan into which the serpentin dipped with fine powder; then with flint and steel to light his match and carefully nurse the glowing spark into a lambent red-hot head; then had the little piece in the serpentin to be lit, and so at last the weapon was ready to be fired. Attempts had probably been made to attach a tinder-box to the side of a gun, but all had failed. Of early attempts at providing self-ignition the “Monks Gun” in the Dresden Museum is one of the best-known examples. This is similar in action to the pop-gun of our nursery days. Alongside the barrel below the touch-hole (which is at the side) is placed a metal box in which moves backwards and forwards a serrated plunger, the extension of which forms a handle. From the top of the plunger case rises a spring in the shape of a serpentin, which presses a piece of flint down upon the serrated plunger. In use the weapon was held in one hand and the plunger worked rapidly backwards and forwards like a bicycle pump, so that the friction of flint and steel produced a spark in the vicinity of the touch-hole and fired the charge. This weapon may be regarded as the legitimate ancestor of the wheel lock.

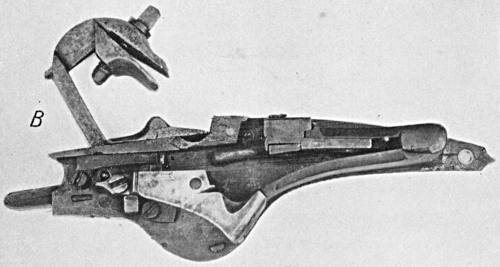

The wheel lock proper was invented in 1515 at Nuremberg, and was a revolutionary departure from all previous methods of firearm construction. The principle was fairly simple, consisting as it does of utilizing the effect of a notched steel disc, revolving at high speed against a stationary flint or fragment of iron pyrites to produce a stream of sparks in the flash-pan. In wheel locks the hammer lies forward of the lock, and, unlike all other firearms, its jaws point towards the butt. This is, in a way, an incorrect statement, for the hammer of the wheel lock is, properly speaking, a serpentin, but instead of holding a match the jaws are made of stouter metal, and hold a piece of flint or iron pyrites.

This is pressed down by a spring at the other end of the serpentin into a pan of powder which communicates by a touch-hole with the charge in the barrel.

This pan has its bottom formed of a steel disc, on the rim of which are chased serrations or channels, and this disc or wheel is outside on the face of the lock, and from it springs the name, “wheel lock.”

This disc was connected by a short link of chain to a very strong spring inside the lock, and was wound up or spanned with a key to a point, where a pin on the trigger lever carried a projecting stud into a hole in the flat surface of the disc, and locked it in the cocked position.

The flash-pan was provided with a sliding lid, which was connected with the internal mechanism of the lock in such a manner as to slide back, exposing the priming powder and allowing the stone in the serpentin to drop into contact with the steel disc when it revolved. This occurred when the trigger was pulled and the stud drawn back into the lock, freeing the disc to revolve against the spring’s compression.

The lock was good, but its construction delicate, and at that period exceedingly expensive. So far as it went it was effective, and as a military weapon was sometimes combined with a match-lock device in case the other lock went out of action.

To fire the piece the flash-pan was primed, the wheel wound or spanned, and the serpentin lowered on the flash-pan lid. When the trigger was pulled, the wheel was free to revolve and driven by the spring spun round at high speed, generating sufficient streams of sparks to fire the priming. In later models an improvement was added in the shape of a pin release to the pan cover. On pressing this projecting pin the pan cover flew back, uncovering the pan for a fresh priming charge to be inserted.

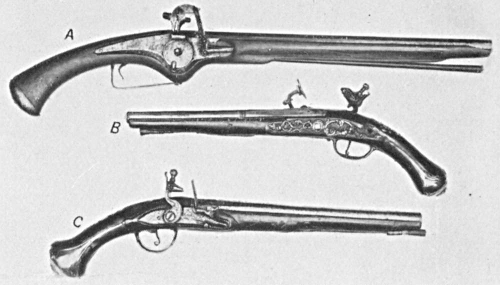

The speedy popularization and perfection of this device gave a great impetus to the manufacture of pistols proper, for now weapons could be concealed about the person and no cumbrous match was necessary. It also proved an ideal weapon for the hunter, as a steady shot could be obtained, and was soon manufactured in pistol and demi-pistol sizes to suit the needs of mounted men.

The first form of wheel lock pistol was the “dag,” or “tacke.” These were short-barrelled, heavy, clumsy weapons, usually of large bore, and with clumsy butts terminating in large knobs or balls—probably with the idea of serving the dual purpose of pistol and club or mace. Practically all sixteenth and seventeenth century pistols were so mounted, and were splendidly carved, embossed, and inlaid. The tradition of the knob butt still lingers, and Tartar and Mongol pistols of comparatively recent manufacture still adhere to the style, having a knob trigger and a heavy ivory ball butt.

In the Wallace Collection are many splendid specimens of wheel lock pistols, or dags, and they are very often made by goldsmiths and jewellers, as well as by armourers, for in those times the craftsman in metals was frequently a general all-round mechanic, besides being a skilled and painstaking artist. The conception, design, and workmanship of Italian weapons of the wheel lock period is often such as to render them gems of artistic production; and to this we owe many of the beautiful specimens that have been preserved to the present day.

Sometimes one comes across baby wheel locks—mere toys, an inch or two in length, of no practical value as weapons, yet perfect models of the larger pistols. These are supposed to be the work of the young apprentices of gun and silver smiths, who showed their skill with their tools by making little models of their masters’ work, exactly as do modern apprentices in the engineering works of to-day.

Many dags were bell-mouthed, and some excellent double-barrelled, both side by side—and under and over—specimens may be found. The tradition of the bell-mouthed, short-barrelled and short-stocked pistol continued for a long time in Spain, where quite recently similar weapons made for breech-loading shot-gun cartridges were manufactured. The same taste in weapons is noticeable in the North African littoral, where a bell-mouthed, or rather trumpet-mouthed, pistol, with a short stock, often carved or inlaid, and frequently of miniature gun-stock shape, was a favourite weapon among the Arabs of the Tripoli, Algiers, and Morocco. (A similar weapon is in the possession of the author, having been brought back from Tripoli by Mr. Allen Ostler, the War Correspondent for the Daily Express at the time of the Italian campaign. It was then in use, and was brought back loaded.)

Neither the dag in its original form, nor the later straight-barrelled pieces, were wonderfully accurate; some were provided with crude sights, but the majority, and certainly the bell-mouthed pattern, were intended for use at close quarters, and were loaded with several slugs to form a scattering charge, rather than a single bullet.

The wheel lock was soon the best military arm, and was adopted by all regiments rich enough to afford them, although poorer battalions still retained the match-lock. During the reigns of Mary and Elizabeth, the official weapons embraced carabines, petronels, which were really long-barrelled, long-stocked wheel lock pistols, and also a hybrid firearm called the “dragon,” whence we get the name “dragoons.” The “dragon” was a brass barrelled semi-pistol semi-carbine, with a fanciful dragon mouth to the barrel. The dragoons were meant to operate as mounted infantry.

The pistol of the Armada period was the long-barrelled, wheel lock petronel, and it is worthy of note that Queen Elizabeth encouraged the manufacture of gunpowder and weapons in the country, although there is no doubt that at that time, and for a good deal later, Continental weapons were superior in material and finish. During the Civil War, both Cavaliers and Roundheads used pistols as part of the equipment of a mounted man. There was no standard bore or length, but in Charles II.’s time it was insisted upon that cavalry pistols should not be less than fourteen inches long over all. The average weapon was the petronel, whose long stock, almost in the same line as the barrel, frequently approximated in shape rather to the gunstock than the easily grasped pistol.

In England wheel locks were manufactured in small quantities, and in perfectly plain material, without decoration or finish. The stocks were made of light, soft woods, and it is seldom that they have lasted to the present day. The majority of wheel locks in existence are the more decorated pieces of German or Italian manufacture, but English pieces are rare—rarer than the armour of the Civil War period, for their wood rotted and they were thrown away.

The name “petronel” comes either from poitrine-al, the French word poitrine meaning “chest,” and indicating the mode of firing, the weapon being butted up against the breast; or from the Spanish word pedregal, “stone,” in reference to the stone or flint held in the lock. Either explanation is good, but neither certain.

In 1630 the flint-lock was introduced, and this was but little used in England until much later, but it is safe to assume that early flint-locks were being used, particularly by rich Cavaliers, during the Civil War period; though for all practical purposes it may be taken that the wheel lock period continued from the time of Henry VIII., whose Yeomen of the Guard carried wheel lock “dagges” in 1519 right down through Elizabethan times—the period of James I., Charles I., and the Civil Wars. They were not officially superseded until the reign of William III. and the beginning of the eighteenth century.