The following information on dry firing handguns comes from Section 10 of Shooting by J. Henry FitzGerald. Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

Dry firing, or, in other words, aiming and snapping the arm without ammunition, is very beneficial to the target shooter and is practiced by nearly every one who shoots. In some ways it is preferable to shooting the .22 caliber arm. It can be practiced in the house morning and night and one is then getting the hang and feel of his favorite arm. In shooting the .22 the light recoil may cover a slight flinch, but in dry firing one sees exactly what he is doing. In quick-draw work dry firing is a wonderful help.

I have seen thousands of cartridges wasted and thousands of discouraged shooters because they did not take the pains to discover what the trouble was and why they were not hitting the target. It is of no use to continue shooting in a blaze-away and trust-to-God fashion. If you don’t know why you miss you never can correct the fault.

Knowing how to stand, how to line up the sights, the trigger squeeze, shooting in the wind, and light conditions are very important, but are you flinching? I know of no better way to correct flinching than by dry firing. You learn all the other things mentioned, you learn to hold the revolver steady at the instant the hammer falls, and you learn not to fight the recoil. Many good revolvers are cussed because the damn thing will not group or place the shots in the ten ring. If the revolver could speak it might say: “If that damn hand would only be still and not try to yank my handle off when the hammer falls I could make a good target.” Do not become careless when practicing dry firing or all benefits which may be derived from it is lost. This is your time to study and find out where you are wrong.

One of the principal reasons why a new shooter cannot make a good score after he has a working idea of the position, etc., is that he cannot control the sway of his arm. It will take weeks and sometimes months to train the arm properly and dry firing will do this, at the same time save money which would otherwise be thrown away.

It does not harm a good revolver to snap it without cartridges and it does help the prospective target shooter, especially in ten and twenty second work. A serious mistake in practicing dry firing for ten and twenty second work is to hold the arm in shooting position and cock, aim, and snap five times without moving the arm. This is not the condition encountered in actual shooting. After the first snap, raise revolver sharply upward as near as possible like the recoil of the arm when a shot is fired, the idea being to accustom the arm to the upward motion of the revolver or pistol and also to accustom the eye to catch the sights quickly as the weapon is returned to firing position.

Captain Max Wendlandt, instructor of the Detroit Police Department, stands at the right side of the shooter and, as the hammer falls, he strikes the bottom of the revolver a sharp blow. This is a very fine substitute for the natural recoil of the arm.

The value of dry firing is evident when our best instructors will recommend and teach it in their police schools.

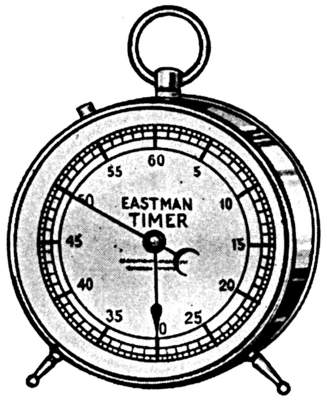

I believe Captain Edward Langrish, originator of the Langrish Limbless Target and expert target shot, has advanced a very fine idea for ten and twenty second shooting by using an Eastman clock used in photography to help the beginner in timing his shots and getting inside the required time. Place the clock where it can be seen easily, toward the target and about six feet away from the raised pistol, which should be empty. When the hand reaches the starting point snap five times, of course, aiming properly at the target with an occasional glance at the clock. Without the recoil of the loaded revolver the ten second time should be between seven and eight seconds and for the twenty second between seventeen and eighteen seconds. The two or three seconds will be consumed in overcoming the recoil when arm is loaded. In a short time this clock practice will be unnecessary as the elapsed time will be known to the shooter within one second.

I remember the late Sergeant John Thomas, U.S.M.C., telling me that he snapped in for seven years before he came to Camp Perry and that year he won the N.R.A. Championship and the National Individual Match. He attributed his success to his snapping in practice. Sergeant J. H. Young, Captain of the Portland (Oregon) Police Team, one of the best revolver shots in the United States, is a great believer in dry firing. The experience and judgment of such men should not be ignored by the beginner.

All dry firing is not recommended; however, a few shots should be fired at every opportunity to check up on the progress. If bitten by the gun microbe this advice is unnecessary. Practice and plenty of it, both dry firing and actual firing, are necessary if the top is to be reached, and the dry firing, at times when no range is available, will assist in reaching the top.

Even experts after a few months’ lay-off will find dry firing the best way to come back, especially in fast work, and when changing from the indoor to outdoor range. If a slight tremor is noticed as the hammer falls this must be corrected, as it is usually due to a slight tightening of the grip or insufficient pressure between thumb and first finger on the revolver.

Use a target of proper size for aiming distance. In an ordinary room a black the size of a dime should be used for dry firing; if on the range use the regular target. Do not use weights or other appliance on the arm, for then the hand and arm are not becoming accustomed to the revolver as it will be used in actual firing.

I believe in full charge loads or very accurate midrange loads at all times, as a slight variation in midrange loads may drop a properly aimed bullet out of the black, where a slight variation in the full charge loads would not lose over a point and the recoil is not disagreeable with full charge ammunition in the modern arms. Stationary sights require this, for all arms are tested with full charge ammunition.

Dry firing is of great benefit in police work where both single and double action shooting are used. It is of especial benefit to the officer who has only fired a few shots. As the officer comes to the firing line he is asked about his experience with the revolver and if he explains that he has only fired a few shots and those some time ago, he is a fit subject for dry firing, which will probably make him double the score he would make if allowed to use the cartridges when he first came to the firing line. The officer experienced in shooting, after he takes a course in dry firing, will probably improve his scores only two or three points but this may be enough to put him over the top.