The following information on practical police and defensive shooting comes from Section 37 of Shooting by J. Henry FitzGerald. Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

Practical police and defense shooting applies to the necessary shooting by police officers, bank guards and armored car guards in discharge of their duty, and, in fact, every one whose occupation it is to protect money and property.

By practical shooting I mean being able to shoot quick and straight. Target shooting is that branch of shooting where the object is to place your shots in the center of a small target and the penalty for not doing so is a poor score. Practical shooting is the placing of your bullets in a human target in such a manner that said human will be unable to shoot at you. The penalty of not being able to do this is the loss of your own life.

We may as well look at this in the true light for target shooting is not sufficient, as that is an advanced stage in the art of shooting. Some of the best quick-draw shots in the world never shot at a target and couldn’t hit one if they did. It is at short range that your life is in danger and at short range that you must be able to place your shots. You may carry a revolver for months and years without knowing how to use it and never have any trouble, and then again you may have trouble the first day or week. If you do not know how to use your revolver you will either forget that you have it and freeze in your tracks, or you will draw it and perforate some innocent bystander, scattering your shots in all directions and no one will be safe, not even yourself.

I have heard the remark, “No one knows what he will do in a gun fight.” This is not correct, because the man who is a practical shot will always give a good account of himself as he has confidence in his ability. He knows just what he can do and he knows that the chances are one hundred to one that his opponent has not his confidence or knowledge, and this confidence and knowledge will be the means of developing a system of self-preservation and defense that is priceless.

I firmly believe that if this system of police shooting becomes universal that crime will decrease fifty per cent. But it must be more than one or two men in a department; all should practice until they are at least fair shots. It does not take months and years to become a fair shot, as it does in target work; it may be accomplished in a very short time.

You have a large target in front of you and the natural qualification of being able to point your finger at a certain object; by handling your revolver a short time you will be able to point the barrel of the revolver as you would your finger, pulling the trigger double action as the barrel swings into line with the target. When you have accomplished this you have the principle of quick shooting at short range and quick draw will be taken up later.

I know a great many officers who never shot at a regular target in their life but who, when their time came to bring in their man, did it with no trouble whatever. I have been called upon many times to instruct a police department of forty or fifty men with a time limit of two or three days placed upon the job. Only one thing can be done in that length of time. Place a Colt’s Silhouette target at five, ten and fifteen yards, and instruct the men in hitting it both single and double action with the right and left hand. All the courses are timed with a watch that times to one one-hundredth or one-fifth part of a second and, in scoring, one-third of the time is subtracted from the scores.

We have heard that little saying that slow and steady wins the race, but quick and steady wins a gun fight, and the quotation that “Colts make all men equal” doesn’t mean that the man who has had practice and knows how to shoot is not the master of the man who doesn’t.

A short time ago I visited a police department and knowing the lieutenant well wished to speak a good word for him to the chief. I said: “Lieutenant S— is a good man for you, Chief, and a fine revolver shot.” The chief said: “Yes, a h— of a fine revolver shot. Missed a man six times the other night who was crawling out of a window twenty-five feet away. I was with him.” Now, I know that this particular lieutenant was a fine shot as far as target shooting was concerned, but he was not a rapid fire shot, and therefore was as wild as any amateur when trying something he was not familiar with.

I have several times been shown revolvers that were used by officers in a shooting bee, with the complaint that the arm did not work properly. I found nothing wrong except that when the first shot was fired the trigger was not released and, of course, the next shot could not be fired. I instructed the guards in one of our large banks a short time ago and one of the officials, in the course of our talk, pointed out one of the guards and told me that he was a coward. When I asked the reason he said that a short time ago they had a little scare and a couple of shots were fired, and that the man in question stood in the middle of the floor and never even drew his revolver. I then asked if the man had ever been instructed in the use of a revolver and the official said he had not. I explained to the official that a man should not be branded a coward until, after proper instruction, he had failed in his duty. A man who has never fired a revolver is probably more afraid of his own revolver than he is of the one in the hands of a gunman.

One of my greatest troubles is teaching officers not to swing their revolvers up over their shoulders and head before bringing it down on the object they want to hit like the movie method. This method makes it unsafe for every one in the range and valuable time is lost, and, as I heard Colonel Rumsey tell one of the shooters at Camp Perry, “The bullet may bounce off your head and hurt somebody.” A close second to the over-the-shoulder and around-the-head variety of getting ready is to aim the revolver at the feet. You are liable to spoil a good pair of shoes, if you persist in this, and it doesn’t improve the foot any, either. Keep the muzzle of the revolver pointed toward the target at all times and keep your mind on what you are doing. Another dangerous proceeding is to turn around at the firing point with a loaded revolver in your hand. Some years ago at Perry on the firing line the contestant on my right asked me if I could see with my glass where his last shot went. I turned around and found that he was aiming his .45 automatic at my belt buckle. I side-stepped and told him that I couldn’t see where his last shot went, but that I knew where my next one would go if he didn’t swing his pistol toward the target.

It seems that I am always quoting something that I have heard at Camp Perry, but one cannot help it who has been fortunate enough to visit the camp during the National Matches. I am glad to see that, while the Police Team and Individual Matches are the big matches, the practical matches are not forgotten. Bobbing targets, running man, running deer, gas attacks and jiu-jitsu are all taught, and this work is of more importance in police work than the target shooting.

One or two lessons will not bring about the desired result, but continual practice will. I have been asked: When is an officer proficient in the use of a revolver? That is when he can handle his revolver with the same speed and sureness of action that the driver handles his car. A car suddenly appears out of a side street without any preliminaries. The brakes go on and the car comes to a stop. Now the policeman comes along the same street, and instead of a car coming out of the side street a burglar appears with a revolver in his hand thirty feet away; can the policeman get into action with the same sure, swift motion that the autoist did? I wonder! The revolver is probably carried under the coat and, being unfamiliar with drawing it, valuable time is lost here; if he is unfamiliar with drawing his revolver he is also unfamiliar with using it when he gets it. We may say three seconds gone and all this time the burglar may be shooting at him because the officer is trying to do something he is not accustomed to do, namely:

To shoot quick and straight and not at a paper target but at a living target capable of shooting back; we know the answer. Fortunate is the inexperienced officer who emerges from this situation alive and if he does the reason is that the other man was as poor a shot as he was. On the other hand place an officer in this position who has mastered the art of quick drawing and quick, accurate shooting; with his trained eye and gun hand, he is master of the situation, even getting his first shot away accurately before the inexperienced man can raise his pistol and fire a shot that has only one chance in one hundred of registering a hit. The difference between inexperienced and experienced officers is that word is passed among the burglar’s friends to keep away from that town, as the bulls there can shoot. The officer who can shoot is a credit to his department and to himself. This question may be asked by some of my readers: Suppose the policeman made a mistake; suppose this was the man who owned the house looking for a burglar? If he was he would not have raised his revolver to shoot the officer, as all officers are plainly marked even to the shiny badge locating his heart.

Many otherwise good officers are killed every year because they do not know how to shoot. It is the cheapest kind of insurance and pays big dividends because it teaches when to shoot and when not to shoot. The inexperienced officer may shoot for no reason at all. The man coming out of the driveway may be in direct line with the house where it would not be safe to miss; the expert would take all this in at first glance and would not miss. I have heard several officers say they would not shoot a man. If this is the case they do not value their own life or their oath to uphold the law. At the present time there is too much shooting by the crook and not enough by the police.

It is just as necessary to know when not to use the revolver as it is to know when to use it. For instance, on a crowded street conditions may arise when it would be dangerous to fire a shot even at six feet. The power of the revolver used must be taken into consideration. It must be remembered that a .38 caliber bullet or larger striking the arm, leg, or parts of the body where no bone is encountered may go straight through and wound some innocent bystander. It is better to let the criminal escape than to have this occur. The officer who does not know how to use his revolver is dangerous because he will either draw his revolver and shoot before the proper time or will be so slow in getting into action that he will lose his own life or be unable to protect the life and property of others. It is not a pleasant subject to speak of shooting a human being, but if we must choose between losing a good officer or a known crook even our sob sisters must agree that the officer should live. The officer is always at a disadvantage as he is known to the crook by his uniform. The crook is not always known unless he breaks a law, which he will not do unless it appears to him that he will be successful and his get-away is assured.

Disarming Holds by Captain Langrish and Lieutenant McGann

The following explanations and illustrations will show the disarming holds practiced by Captain Langrish and Lieutenant McGann.

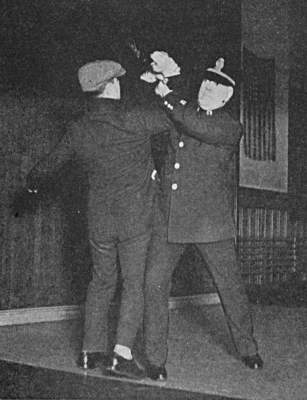

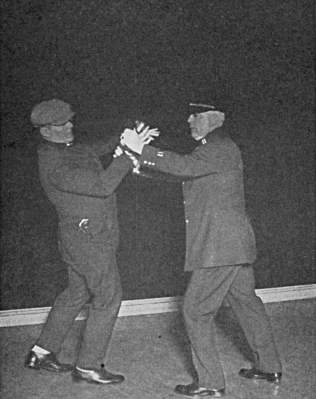

Positions 1, 2 and 3.

From hands up position drop left hand, thumb on cylinder, turn revolver away from body.

With right hand grasp opponent’s right wrist, force revolver away at an angle that will cause opponent to loosen hold on revolver.

Continue pressure until opponent’s finger is caught by trigger guard. Always practice with revolver empty.

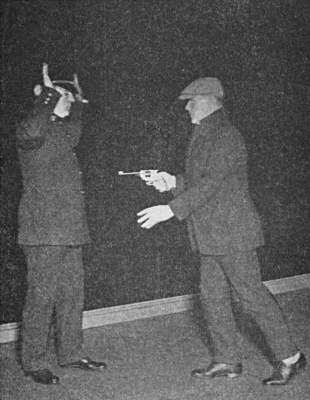

Positions 4 and 5.

Opponent using revolver as club, revolver grasped by barrel. Raise right arm in front of head, catch opponent’s wrist with right hand as he attempts to strike.

Force arm backward, lock left forearm inside opponent’s elbow, grasp your right wrist with left hand, step forward, increase pressure on opponent’s arm until revolver is released, then throw him over your right hip.