The following information on rear and front sights for revolvers comes from Section 15 of Shooting by J. Henry FitzGerald. Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

The question which bothers many shooters is whether to purchase a revolver with adjustable or stationary sights. And there is a great deal to be said in favor of both models.

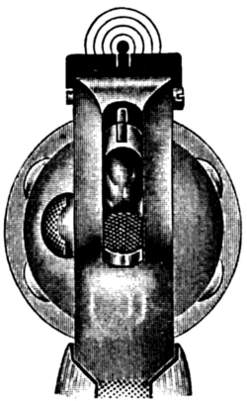

The adjustable sights are preferable for those who wish to use mid-range ammunition or special loads and reload their own ammunition, and for those who wish to change and try out different sights. In a very few minutes the sights may be changed to 1/8, 1/10, or 1/12 inch partridge sights, large or small bead, and gold or ivory. For trick shooting the revolver with adjustable sights is preferred.

I have noted many men on the firing line who are continually changing their sights and to those men the stationary sights would be a blessing. The sights must, of course, be adjusted for the ammunition that is being used, but after once being properly adjusted need not be changed as long as the present sights are satisfactory and no change made in the ammunition.

If long range shooting is indulged in, a higher rear sight is necessary and this is sometimes true if mid-range ammunition is used. If the revolver is shooting to the left move the rear sight to the right; if it is shooting to the right move the rear sight to the left. In other words move the rear sight the way you wish to move the bullet hole in the paper. If the rear sight is adjustable for elevation and windage move the sight to right or left, high or low, as you wish to move the bullet hole on the paper. If the front sight is adjustable for elevation and the arm is shooting low, lower the front sight. If the shots are going high raise the front sight. Move the rear sight the way you wish to move the bullet hole in the paper and move the front sight in the opposite direction from the way you wish to move the bullet hole.

In many matches the adjustable sights are not allowed. The N.R.A. Individual and Team Championship matches at Camp Perry do not allow them. However, the stationary sights are now so well made that the adjustable sights have little, if any, advantage over them. The only change needed is possibly to open out the rear sight to admit more light in the stationary sights.

If an arm has been shooting in the ten ring and on the next trip to the range it should group to the left or right, do not blame the arm and do not blame yourself, until you are sure that the light conditions are not the cause of your trouble. There is no reason for changing sights on a properly sighted arm. It is better to hold to the right or left as the case may be, for with normal conditions (conditions under which the arm was properly sighted) the arm will again shoot center.

If a new arm with stationary sights is purchased which shoots low, it can easily be corrected by filing off the top of the front sight. If it is shooting slightly high this may be corrected by a lower six o’clock hold. If a close six o’clock hold carries the shots out of the nine ring at twelve o’clock, then it is best to return the arm to the factory for correction. Shooting slightly to the right or left may be corrected by filing the rear notch on the side toward which the bullet hole should be moved, but if shooting two or three inches to the right or left the arm should be corrected by the manufacturer.

Proper sights and proper sighting of the side arms are very important for without these the best revolver in the world is useless. We will, of course, always have the difference in eyes to contend with for very few hand gun students require the same sight adjustments.

At the 1927 Camp Perry matches one of my friends asked me to bring a six-inch barrel revolver to the firing line as he wished to purchase a new one. I brought one that I had targeted at the factory and for my eyes was shooting perfectly. My friend took it on the firing line and after three scores returned it to me with the report that it shot too high, all eights at twelve o’clock at twenty-five yards. The revolver lay in my tool box and another friend came along and asked if he could try it. He came back after the trial saying: “Fitz, that revolver shoots just two inches low and if you will file off the top of the front sight to correct this I will take it home.” There was a difference of over four inches at twenty-five yards in the shooting of the two men and both were experts. Nothing except the death of a very dear friend will bring such a sad and sorrowful expression to a man’s face as to purchase a new arm and find it does not group the shots in the ten ring. Still the arm may be shooting perfectly for the man who targeted it and for many others.

Another thing to take into consideration is whether you are shooting at the same size bull’s-eye that the arm was targeted for. Arms targeted at fifteen yards on a twenty-yard target must shoot low at fifteen. The properly targeted six-inch barrel revolver shooting center at twenty yards will, at fifteen yards on the same target, shoot below the center in the bottom half of the black. The revolver sighted correctly for the twenty-yard target at twenty yards will, of course, shoot low at twenty-five yards on the Camp Perry Police target, but will be nearly correct at fifty yards on the Standard American target. Holding with a wide white line at six o’clock or even one inch should not affect the score except in cases where the contestant insists upon holding in the black; world’s records have been made by experts who hold in the center of the black. The majority of shooters, however, hold at six o’clock or with a white line.

The one-tenth inch sights are now universally used either in stationary or movable form for fine target shooting. In choosing sights the length of barrel must be considered, as the one-tenth inch front sight on a seven and one-half inch barrel will not look any wider than the one-twelfth inch sight on a four-inch barrel.

Another peculiarity in rear sights is that a perfectly square notch will appear to tip in or narrow at the top and, of course, when the notch is cut with a wheel cutter this condition could not exist. To correct this each side must have a three-degree angle outward which makes the sight, when held in shooting position, appear perfectly square. If the front sight should be slightly tipped to right or left the rear notch should be changed to allow for an even distribution of light on each side of the rear sight, and the top of the front sight should be square with sides of the rear notch. If filing rear notch the end nearest the front sight must be filed wider than the rear end to keep a clear, sharp edge nearest the eye.

Many odd forms of sights are used, such as the square rear notch with a bead front sight; the bead front sight filed flat on top and a U rear sight; rear sight without a notch but with a one-thirty second inch piece of platinum or silver imbedded in the steel sight in a perpendicular position; and a bead sight may be used with the entire bead held on top of the white line. All these are very good and are eligible in matches where movable sights are allowed.

Smoking the sight with a miner’s lamp or P.J. O’Hare’s famous sight black will close up the rear notch and widen out the front slightly, but this will only be noticed in cases where very little light appears when gun is held in shooting position. It greatly aids the shooting accuracy in the bright sunlight. Paper matches and some of the wooden ones may be used to black the sights, but many of the imported matches will rust the sights. Some of the sights now furnished on revolvers and pistols are sandblasted or roughened and this is an aid to fine shooting in a strong light.

In the days of the powder and ball arms and later in the days of the old Peace Maker the sights all seemed to run to the knife edge variety, and while we read of the wonderful shooting done with these arms I believe that some of the stories were slightly exaggerated. They did not have arms to compare with the ones we have today. The range of our modern revolvers is three times greater than the old powder and ball revolver and accuracy has increased in proportion. I am not going into the description of old and modern revolvers for these have been thoroughly described by Major Hatcher in his book, “Pistols and Revolvers”; but I have met many of the Western gun-toters of the old school and the West did develop the fastest men in the world with side arms because they found it necessary to be excellent shots if they wished to live to enjoy old age.

I find in revolver sights as in Lyman rifle sights that the eye will naturally center the sight, allowing the same amount of light on each side, and I am a great believer in plenty of light. I use the one-eighth rear sight with the one-tenth inch front sight, which combination in smoky ranges is far clearer than the close sight; even when shooting at shells and small objects it is just as accurate.

Years ago at Camp Perry I used to take along about three hundred wide (one-tenth and one-eighth) sights for the contestants and use them all. Then I commenced to open out the rear notch and found that this would answer the requirements of seventy-five per cent of the shooters. This refers to the .45 automatic, which is generally used there, and due to the shortness of this arm the regular front sight is fifty-eight thousandths of an inch. Plenty of light is preferred by many of the experts, especially in rapid fire.

While on the subject of sights I may mention that my observation in many years of testing revolvers has taught me that, though ninety per cent of the target men are satisfied with the way arms are sighted, the other ten per cent could only be satisfied on the first trial by sending to the tester one of their favorite arms, sighted properly for their eyes, then the sight could be corrected on the new arm.

It is best to send a target with the arm submitted showing group and point of aim. Arms shooting right or left, high or low, may be corrected in the same way. If arm is not submitted when another is purchased, the only way is to shoot the new arm as it is received, and return target and arm for correction. Very few corrections are made on the arms of expert shots.

I sometimes have a revolver handed to me as inaccurate, in other words, shooting all over the target. I look at the gun to be sure that I have not been handed one of those smooth bore shotgun pistols and then ask to see the target, for a glance at the bullet holes will place the trouble. If the bullet holes are perfect and the man is shooting standard ammunition the trouble is with him. The sights may be wrong, but the high grade revolver or pistol will group with correct ammunition and sights can easily be corrected.

I wonder how many of the shooters ever study the bullet holes made by their favorite arm. I remember several years ago two pistols were shown me,—one with one turn in sixteen inches, the other with one turn in fourteen inches. They were .22 caliber guns, using two hundred-yard ammunition. I left the room while both pistols were fired at fifty yards and on my return I could easily pick out the bullet holes made by each pistol. The holes made by the fourteen-inch twist were perfectly round and showed the perfect rotation of the bullet, and the bullet holes made by the arm with the sixteen-inch twist were ragged, not as clear cut, and showed a slight tippage. The correct twist for hand guns chambered for the present .22 caliber ammunition is fourteen inches.

If bullet holes are watched closely many interesting things may be noted. A new arm will not always make the perfect holes in the target that it will after fifty or one hundred shots. The bullet in flight may be compared to a top, a slight stagger as it leaves the muzzle, then after a few feet settling down to a steady flight and again the stagger as it reaches the end of its flight.