The following information comes from Section 34 of Shooting by J. Henry FitzGerald. Shooting is also available to purchase in print.

Building a Championship Team

By Capt. J. H. Young

Just a few words of advice to those who wish to develop a good, strong revolver team.

First, check up on the timber you have to work with, or, in other words, have every man report for practice who wishes to try and make the team. Be sure to reject any man who does not want to shoot on the team, regardless of how good a marksman he may be. One unwilling member on a team, who does not think he can be told anything, will spoil a whole team. A team coach must have the good-will and confidence of every member on the team or he will make no progress.

Now let’s assume that you have fifteen men to try for the team. Start them shooting, and note carefully the men who have the steadiest nerve and the best eye. You can soon dismiss several and save ammunition. As soon as you can tell who the most promising shots are, you can thin them down to about twice the size of your team. Then after a little more practice and instruction, hold an elimination contest, say about twelve matches. This will give you an idea of what competition will do to each man. You can then readily select your team with a couple of alternates and start your real training in earnest.

A great deal can be said about the way to train a team, but I will try to touch lightly on some of the most important points.

First, start your men in dry snapping. This is to a revolver shooter what running the scales on a piano is to a student of music, as you can watch the barrel of his revolver and see how much flip it has when the hammer falls. This you could not do if the gun was fired. Instruct each man to aim carefully, as if he were shooting in a match, and squeeze gently until the hammer falls, but still hold the gun on the bull’s-eye for some moments after the hammer falls. If the gun has a barrel flip when the trigger releases, the student hasn’t just the proper hold on the stock of the gun, or he has jerked on the trigger, or perhaps he has squeezed the stock with his whole hand, which is wrong. The trigger must be squeezed with the index finger. However, you may lay the thumb up along the frame of the piece and as you squeeze with the index finger press the thumb against the gun slightly. This will steady the gun and prevent the barrel flip.

After all of your team understand the trigger pull, take up the position of the body. Every man will have some peculiarity about his position, and he will insist on using it, because he made the team that way, but you must insist on correcting the position and see that it is done, but do it by reasoning with the student rather than by strict discipline, as here is where you get the confidence and good-will of your team. Now about the position of the body. Teach each man to face at an angle of about forty-five degrees from the target, and insist on this because if he faces squared to one side at an angle of ninety degrees, he will have to turn his head to the right so much that he is likely to hamper the circulation of the blood through the jugular vein. On the other hand, if the student faces toward the target he will have to bring his hand over in front of the body, which puts the sights nearer the eye and also gives him an awkward position.

Now about the distance. The feet should be apart, which depends altogether on the conformation of the man. A tall man with long legs must stand with a greater stride than the shorter man. The left hand may be placed on the hip or in the trousers pocket, or left hanging naturally by the side as the student wishes. The head must be held erect, not reared backward or stooped forward, for if the student keeps shooting he some day will have to shoot with glasses, and if taught to hold his head in the proper position, it will come natural for him to see the sights through the center of his glasses, which one must do to get correct vision.

After you have the team trained on the position, the trigger pull and the proper grip on the handle, see that they do not slight any of these details, and each time you fall in for practice make your team dry snap a few minutes. This will steady their nerves and give you a chance to check on all positions and correct any error that they might make before they start shooting. Keep a record of all scores shot by your team so you can tell how they are improving. Begin with the slow fire first, and fire nothing else until they can make a good score. Then take up the time fire, but be sure to do some more dry snapping, timing the men, or have some one else do the timing while you check all other details and correct any errors.

After your men have learned the time fire, take up the rapid fire in the same manner, letting the team shoot together. You might run a little over the allotted time for rapid fire until the scores begin improving, then cut down the time to the regular ten seconds. Much time must be spent on the rapid fire so as to get the men accustomed to the allotted time.

Now you have your team working nicely, and it is up to you to guard against any discord among the team, such as jealousy or ill-will toward each other. Study each man’s disposition carefully and coach him accordingly, as every man is different when he is firing. While one man may be talked to between shots or between strings of shots, another must not be spoken to at all while he is firing his score; never speak to any one while he is aiming, but correct his error between shots. But if he has had the proper instruction in practice he will not have to be corrected while firing for record. Do not allow your man to figure what score he or any one else is making if you are shooting a match, say thirty shots per man. Each competitor has only one thing to think about and that must be thought about thirty times, and this one thing is the shot he is firing. Just ease the trigger off at 6 o’clock when that shot is scored, forget it and start thinking about the next one and let the coach attend to all other details, such as spotting and challenging of shots. Be sure that your men know the number of the target they are to shoot on and see that they shoot on no other, for many an important match has been lost by firing on the wrong target.

And let me say once more, above all things, do not allow any animosity to arise among your team members; just remember that harmony is the strength of all organizations.

Camp Perry 1918 to 1928

By Major H. L. Harker

Away back about 1911, towards the close of one of those beautiful Indian summer days, while ascending a very long, steep hill full of tangled greenbrier and other matted undergrowth, seeking the wary cotton-tail rabbit with dog and gun, I arrived at the conclusion, that, if it was shooting I was looking for, it was to be in some other form. I had shot small rifle at stationary and moving targets for many years, so I thought I would try revolver shooting. Before very long I purchased a .38 D.A. Army Colt and sought acquaintance with some National Guard officers in whose armory there was a three-target range. Among those who shot in this range were Major S. J. Fort and Sergt. W. A. Renehan. It was through these two men that I first learned of Camp Perry, but I didn’t know what it was all about at that time. As the winter season approached, all hands being members of the Baltimore Revolver Club, we entered the indoor matches of the United States Revolver Association and shot successfully through these matches for several seasons. The World War was now shortly to come on and when it finally broke, and likelihood of this nation becoming involved, there was a great stimulus in revolver and military shooting.

After our government entered the conflict, it was found, notwithstanding we prided ourselves “A Nation of Riflemen,” that we were far short of sufficient instructors in the regular service to properly train the men of the National Army who were to represent us at the front. Hence, in the spring of 1918 the Small Arms Firing School was organized at Camp Perry, Ohio, and by reason of our qualifications with the revolver, Major Fort and myself were commissioned and ordered to report to the commandant, Lieut. Col. Morton C. Mumma, at Camp Perry, Ohio, where we were to teach the revolver and automatic pistol. Thus was I formally introduced to Camp Perry, upon which I desire to write, and where I have spent many pleasant hours and made acquaintance with many fine men from all over the United States and its possessions. It is these men, the shooting clan, that I select as my colleagues, whether it be in peace, war or shooting holes in paper targets.

Upon arrival and officially reporting, we next secured quarters, some securing berths in the clubhouse and others being assigned to tents near by; however, near enough so we could hear that familiar early morning cry—”Roll call, everybody out.” This took place in the basement of the clubhouse. Colonel Mumma usually presided, assisted by Major Brookhart and Major Libby. You will realize that there was lots to be worked out before classes could be properly handled. A plan of operation was drafted and a refresher course put on with us, who were to offer the instruction to the students. When I say that this was some band of shooting nuts, I am putting it mildly; even the little frame house now occupied as a range house for the pistol was named “Squirrel Inn.”

There were about seventy-two in the personnel of the school, forty-two of whom were instructors. They included some Britishers, who had seen service across and who exerted their efforts in the snipers’ section. Captain Richards, now with the Winchester Company, was with the snipers.

Major S. J. Fort was in charge of the Pistol Section and had, for his assistants, Captain Thomas LeBoutellier and Lieut. John Dietz, both from New York, and the writer. The other instructors were known as Rifle Instructors, who were assigned about thirty men to whom they taught the rifle from the beginning of its manufacture to the completed human element—”The Expert Rifleman.”

One hour out of each day these rifle instructors marched their groups to the pistol ranges or to some designated spot, generally in the shade of those fine old trees on Sandy Kerr’s lawn, where we proceeded to expound to them the mysteries of the 1917 revolvers and the Colt’s automatic pistol, both of caliber .45. At first the pistol firing was conducted on the east end of the present 200-yard rifle butt; later, on a temporary range of twenty targets installed on the beach near the clubhouse. This was in charge of Lieutenant Dietz and generally referred to by the Colonel as the “Jon Dietz Range.” The groups moved to and from these two ranges every hour of the working day. The pistol ranges were indeed very busy places. There were five classes in all that passed through the school from its opening in April to the early part of October, 1918, each class spending about five weeks there. The students consisted entirely of officers, from second lieutenants to colonels, and were assembled from the many posts throughout the government’s possessions. These men, being far above the average, learned quickly and became very good instructors. After receiving a Certificate of Graduation from the school, they were returned to their respective stations to instruct the men of their commands.

In September, 1918, and in the midst of the work with our last class the National Matches were staged. As the war was still on and many of the country’s best shots engaged in the training of men, the matches were not very well attended, except by those of the class and a few outsiders who had not been gobbled up in the draft. The pistol match, I do recall, was a record breaker for attendance, the number shooting being more than 1,100 and taking twenty-three relays to run it off. It was won by Mr. Frank Parmly of Kansas in the last relay.

The matches being over, the work of finishing up the last class again demanded attention, and I recall vividly the day for pistol qualifications. The day came in cloudy and overcast, and about the time the relays were all squadded a hard, driving rain set in. The work had to be completed that day and the several delays on account of torrential downfalls put the last squad through at dark, and every one soaked to the hide and some hungry. I think I turned in after taking a good hot shower and without supper. It now being October, the cold days began to put in their appearance along the shores of Lake Erie, making it undesirable for school purposes, which meant a change. It was rumored that we were to be grouped into instruction units, composed of a major in command, six riflemen, and a pistolman, and sent to six of the large cantonments. You can imagine the anxiety with which we watched the hand of Colonel Mumma, which held the chalk from which was to flow the names to comprise the units and where sent. I did not have long to wait, for the very first cantonment listed was Camp Travis, San Antonio, Texas; then the names, Major Krembs, and then mine. In a day or two our orders came through and we all went our several ways, planning to meet at the large hotel on the Plaza in San Antonio next to the Alamo on the morning of the 14th day of October, 1918. Once assembled and after breakfast we went to camp headquarters, presented our orders, and were assigned quarters. Then began the work of organization and some pupils to work on. This being something new to this camp, we had hard sledding for awhile, as it seemed that everybody was too busy with the new recruits, putting them through their “squads right,” with no time left for shooting. However, I was detailed by the Major to scrape together a pistol class, while he and the others worked for the rifle.

I soon located by settling on the artillery. Now, every one knows when it comes time for the Field Artillery to use pistols things are very desperate, and it is about time for all hands to wish they were home under the kitchen stove. However, they were to be taught, so that ended any argument. Next, I inquired about their pistols. Well, it so happened that none had been issued, so the Colonel got busy and borrowed some from the 35th Infantry, then in camp, which enabled us to get started. After a few days this Colonel became very friendly and he had his chauffeur call for me at each session of firing, and at the close of the day I enjoyed the privilege of riding with him in the rear seat, much to the chagrin of my Major, who said he couldn’t even get a jitney to take him to town.

In a week or so a school of two hundred and fifty-one was organized and we all proceeded to Camp Bullis, a target and combat range about twenty miles from Travis. It was while we were at this camp that the Armistice was signed and at the time when we were in the midst of our instructions. I recall very well the Sunday afternoon following the Armistice, I put through the class in pistol firing for qualifications. Shortly after this we were ordered to Camp Benning (now Fort Benning), Georgia, where we formed the nucleus of the Small Arms Division of the Camp and had under instruction at that time one hundred and thirteen men from West Point Academy. After this class, there being no urgent need for our services as instructors, we were assigned to the several points where arms from demobilized troops were sent for inspection, cleaning and packing, after which most of us accepted our discharge or went into the Reserve Corps.

In 1920, Col. Morton C. Mumma, having been selected as Commandant of the National Matches, surrounded himself with as many of the personnel of his old school as was possible and requisite, and with others I was asked to serve as range officer at my same old stand, “The Pistol Range.” This reunion with the boys of the school was a very pleasant one.

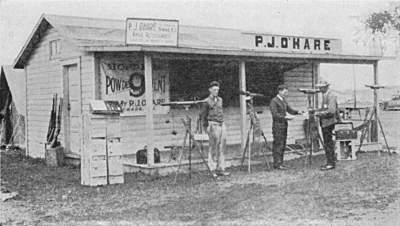

It was at this match that I first made the acquaintance of Mr. J. Henry FitzGerald of the Colt Company, better known by his old friends as “Fitz,” and easily told at great distances by his size and his ten-gallon hat which he invariably wears. This year, Commercial Row was along the east side of the main street entering camp at a point where Paddy O’Hare is now located. Fitz did not do quite as much repairing on the line in those days and at night the Colt tent was usually packed to “busting” to accommodate those who wanted repairs made and also with those who came to tell the latest jokes, good and otherwise, that could be gathered from all over the world; while Fitz was busy toiling in the rays of the old “Gasoline Lantern,” taking out “creeps” and carefully placing them in a tin box to prevent them from getting in some other gun; and substituting “crickets” for sear springs when the customer was not watching. The only reason the crickets didn’t work was when their frail legs would break. With all the work he always found time to come in on the laugh of a good joke and offering one in his turn. Many of the old timers will recall these pleasant evenings.

The next year found Commercial Row on the west side of the same street. It was this year that we had quite a lot of rain and several heavy blows from the lake. On one occasion most of the front row tents were blown down and General Phillips, then Secretary of the N.R.A., found himself wandering around in the rain all dressed up in his pajamas, his tent having gone skyward. There was at least six inches of water in the area occupied by the competitors; the boys had to undress atop of their cots and, during the night, through twisting and turning, some of the wearing apparel usually fell overboard. It was a common thing to hear some fellow ask: “See anything of my shoes floating around here?” and after all this they were ready to go at 7:30.

As I have been on duty on the Pistol Range every year since 1920, I have seen Camp Perry grow from a normal shooting camp to the one we have just passed, the largest ever, and in this time have made the acquaintance of the majority of the pistol shooters of the country, many of whom I know intimately. There is, of course, like in every group of human beings, the fellow who becomes a pest in some form or other. Some will insist on firing the last shot on the range, whether or not it is too dark to see the target or whether it is raining so hard the pasters slip off, which gives him a chance to claim all the open tens. Then we have the fellow who, after all rifle action has ceased, makes a run for the pistol range, only to find all the targets taken down except, possibly, the Instruction Target, setting off on the flank: “Say, Captain, can I take just one shot at that one?” One fellow came along with his .45 automatic and picked up a trigger weight to weigh in, cocked the gun, and hooked on the weight—”bingo” right by Colonel Rumsey’s ear. He forgot about the one in the barrel. Another fellow only got off four shots in a ten second string: “Captain, can’t I shoot six next time?” Then we have the fellow who gets nervous waiting for the targets to appear and proceeds to scratch the side of his head with the cocked pistol: “Say, cut that out, and stand at ‘raised pistol’; if that gun goes off the bullet will ricochet off your dome and kill some one.” While I am pretty well used to all these tricks, occasionally some fellow pulls a new one; so just keep smiling, take things as they come, and order up the next relay.

Keeping the pistol game going at Perry, with only fifteen operated targets, always presented quite a problem with 600 pistol shooters in camp. Shooting on the temporary ranges is really the best practice, as a man has the advantage of viewing his own shot groups; but, inasmuch as it was necessary to hold the major matches on the rifle butts, it was hardly fair to the men who had to practice on the non-operated ranges, owing to the line of fire being at quite an angle above the horizontal. This will all be obviated now, as the new pistol range of seventy targets, started in 1928, will likely be in shape for the 1929 matches, when it is hoped we will have sufficient targets to take care of all the matches and practice. There is a great stimulus in pistol shooting throughout the country. This is reflected in the National Match, the entries totaling 619 in 1928. Competition is keener than ever before and the man who wins in any event deserves his honor.

Fitz is the outstanding figure of the hand-gun clan and being a practical shot in any position, slow or rapid fire, quick draw and whatever else there is, he understands their very needs and the boys come from far and near to bring him their ills, whether real or imaginary. Long before he arrives in camp I am asked: “When is Fitz coming?” and those who are not acquainted, say: “Where can I find Mr. FitzGerald?” Well, pretty soon Fitz drives along in the family coach dragging the trailer which contains all usually found in a first-class hotel and a gun factory combined, and takes possession in No. 1, Governors Row, Squaw Camp. As soon as I notice this movement I get in touch with the Camp Director and have a tent put up in the rear of the pistol firing line where he can be near at hand and attend to the shooters promptly. Fitz formerly opened shop under a large wagon umbrella, but his popularity and need for his service caused the change to more commodious quarters; hence the tent. From the time he first opens his tool-kit until after the National Team Match he is a man to be pitied and well deserves a reprieve to grow some new skin on his finger tips that are about worn through. We are all glad when the last shot is fired, but before the snow of the following winter has disappeared, we are eagerly looking forward and scanning the pages of the “American Rifleman” for the announcement of the date of the next National Match.